| Critical and biographical information on Henry Reed, World War II British poet, critic, translator, and radio dramatist — author of "Naming of Parts" |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

O'Toole, Michael. "Henry Reed and What Follows the 'Naming of Parts'."

In Functions of Style, edited by Davis Birch and Michael O'Toole. London:

Pinter Publishers, 1988. 12-30.

1 Henry Reed, and what follows the 'Naming of Parts'* Michael O'Toole

Murdoch University

The first aim of a stylistic analysis, as I see it, is to provide as detailed a description as possible of the transmitted text of the work in question. No other form of literary criticism engages with the actual text so closely or attempts to apply a coherent analytic method and a consistent descriptive vocabulary. Naturally, it will take account of many possible 'readings'—including readings aloud—but the main source of evidence is the printed text, that edition agreed by the author, editors and publishers as the definitive one to be transmitted to the contemporary and future public. Secondly, a stylistic analysis inevitably prompts and deepens the process of interpretation. A dialectic between precise description of the details of linguistic form and less precise intuitions about the meanings of the poem and its parts becomes a 'hermeneutic spiral' intensifies our awareness and deepens our understanding of the text.1 A third and related aim is to test, against a coherent, valued and experimental piece of language, the power of the chosen model of linguistic description. We assume, for example, that a poem is more 'self-contained' than most kinds of non-poetic text and that its internal patterning will be readily susceptible to a multi-dimensional description. We assume that one reason why the poetic text is valued by the culture out of which it grows is that it represents a higher degree of philosophical awareness and linguistic subtlety than other kinds of text. And, in so far as it represents an experiment with the language and thought patterns of the culture, we may assume that it will provide a special kind of test for the analytical and synthesizing powers of the descriptive model. Stylistics is a critical discipline in that it is one of the possible approaches to literary criticism. For many, though by no means all, of its exponents, it is a discipline critical for literary criticism. Without a precise description of the literary text there is neither a point of departure for other types of criticism nor

* I am grateful to Terry Threadgold, David Birch, David Butt, Michael Halliday and the

participants in the 3rd Language in education Workshop in Brisbane for their responses to the

poem and some of the ideas expressed in this chapter.

[12]

a point of reference for divergent opinions. It is therefore in a position to be

critical about the critical process, and there are some good examples of long-standing

critical debates of a conventional kind which have been shown up as

quite hollow and insubstantial once the language of the work or works

discussed has been analysed in depth.2 But stylistics should also be a

self-critical discipline: it should be aware of the limits to what can objectively be

described, the complexity of the interconnections between the describable

details and the ineffability of the ideas and feelings shared by the poet and

readers for which the linguistic structures are the vehicle; the parts that can be

named.

Henry Reed's poem 'Naming of Parts' offers a challenge to stylistics by showing how limited and limiting the mere naming of parts can be, and by offering glimpses of the human and natural reality that may be damaged by too much naming. The poet challenges us to put aside our precise and constraining technical terms; to give rein to our intuitive responses to the world around us; and to recapture the wholeness and integrity of experience unmediated by our obsessive naming. But perhaps I am naming too readily and too early the oppositions around which for me, at any rate, Reed's irony plays. Let us start with a stylistic description. First, here is the poem as it appears in the group of poems that Henry Reed wrote during the Second World War which he called Lessons of War. To-day we have naming of parts. Yesterday, [13]

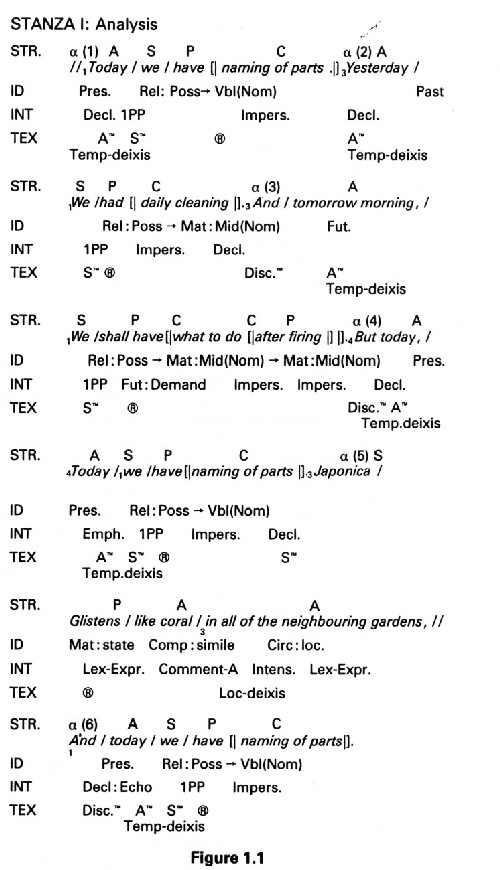

And the breech, and the cocking-piece, and the point of balance, Now let's look at what is revealed by an analysis of the linguistic structure and the main options Reed has selected at each rank for the Ideational, Interpersonal and Textual functions. I will discuss the analysis a stanza at a time in order to highlight the patterning of the options Reed has selected in each of the three functions and the interplay between them. We will then be in a better position to study the patterning of foregrounded elements across the whole poem, to relate that patterning to the interplay of registers and poetic themes and to attempt an interpretation. The linguistic analysis should lead us to a hermeneutic synthesis. STANZA I: Discussion In the ideational function the most obvious feature is the recurrence of grammatical metaphor. In every clause except (5) the essence of the process has been nominalized and becomes the complement of a dummy verb (have, do) or a preposition (after). Thus in (1), (4) and (6) the underlying process-participant relations would normally give: We/are naming/parts; following the sign for grammatical metaphor (→) this is shown as Vbl (Nom), i.e. a nominalization of verbal process. Similarly, clause (2) nominalizes a material process: the 2-participant We/clean/the rifles becomes a noun and loses its participants: Mat:Mid (Nom). The grammatical metaphor becomes more complex in (3) where the underlying modulated material process what you should do is nominalized into an infinitive clause and itself subsumes a further nominalization as its adjunct: after firing. The accumulation of nominalized elements from (1) to (3) appears to parallel the growing complexity of the time adjuncts: To-day—Yesterday—And to-morrow morning. At the same time there seems to be an unconscious irony in the degree of precision of these nominalized processes in relation to the temporal deixis: today we have something rather precise; yesterday we had (i.e. completed) something which is done daily (i.e. never completely); and tomorrow morning (a very precise future) we shall have the vaguest possible activity; but today, today (repetition for reassurance) we have something quite precise. Clause (5) has a rather vague and general locational deictic, in all of the neighbouring gardens, but a process that is a direct expression of the material state of a particular subject, Japonica glistens. No grammatical metaphors here, with their rather loose semantic links; rather a literary simile, like coral, that makes the description of that material state even tighter. In the Interpersonal function each of the clauses (1)-(4) and (6) combine a marked first person plural subject (1PP), we combined with a highly [14]

[15]

impersonal complement; rather we should say depersonalized, since one of the effects of the nominalizations of the process we noted in the last paragraph is to remove the agents: who names parts? who cleans daily? who does what after who fires? It is not clear at this stage whether the we is inclusive or exclusive: does it really include the speaker, or is it more like the exclusive we used by doctors and teachers to patients and pupils, supposedly to reassure by establishing what Erving Goffman calls a 'with', but actually reinforcing the differential in power relations? The contrast again occurs in (5) where a well- defined subject establishes the declarative mood of the clause, Japonica glistens ... and the verb is lexically expressive, the simile is a common adjunct and the emotionally reassuring neighbouring is intensified by all of. In spoken language, of course, a great deal depends on the intonation, and it is one of the virtues of Halliday's (1973) model of language that the function of intonation is clearly assigned (see Tone), at the bottom of the Interpersonal column on the chart (Table 1, p. 8). Although the boundaries of the tone group do not necessarily coincide with those of the grammatical units of clause or group, intonation is still a major vehicle for interpersonal meanings, assigning roles (declarer, questioner, orderer, requester, exclaimer, doubter, etc.) to speaker and hearer and carrying—by implications of contrast—a strong sense of what Bakhtin and Voloshinov called the 'alien discourse' of the other speaker.3 Different readers will interpret a poem with different divisions into tone-groups and different tones. I have indicated my interpretation by putting a subscript number of the tone just before each new tone group. Thus clauses (2) and (3) each have two tone groups: a low rise (Tone 3) for the time adjunct and a firmly declarative (Tone 1) for the process. Clause (4), however, breaks this pattern by having a qualificatory (Tone 4) on each of the repetitions of today, presaging the finality of (Tone 1). Clause (5) stands out this time by not having a completed intonation curve: its two low-rise (Tone 3) groups are full of expectancy, but the intonation curve is completed by the (Tone 1) of clause (6). The three almost identical clauses, (1) (4) and (6), are all intoned differently depending on their position in relation to preceding tones. In the Textual function the obvious pattern is the recurrence of temporal adjunct followed by subject in theme position in (1), (2), (3), (4) and (6), while (5) has the unmarked subject as theme. We should note, however, that (3), (4) and (6) differ in also having a discourse adjunct and or but as part of the theme sequence. Even here, there may be a distinction between And in (3), which must be within the drill sergeant's discourse, completing his curriculum of activities, and But in (4) and And in (6), which could either belong to that same discourse, or could be part of the army recruits' discourse. Now, hold on, where have the 'drill sergeant' and 'army recruit' sprung from? We have just completed a structural functional analysis of one stanza and suddenly these dramatis personae become determining factors in the grammar without even being mentioned. Well, the fact is, of course, that we are using a lexico-grammatical model for our analysis and there are clear indications of the field of activity in the lexis. In fact, the cumulative tendencies we noted from clauses (1) to (3) apply here too. What might be any [16]

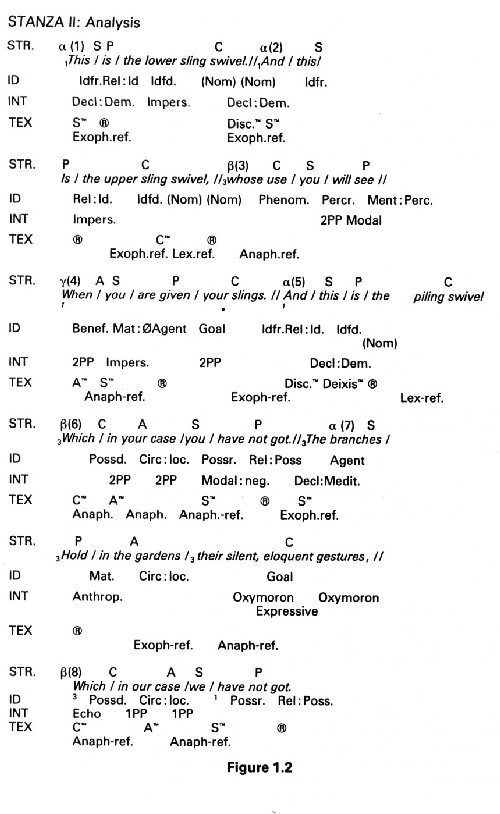

field in naming of parts becomes something that requires daily cleaning in (2) and is capable of being fired in (3)—clearly some sort of guns. Moreover, a tendency towards nominalization often betrays a bureaucratic or overregimented mind. But the tenor of the discourse carries clues as well: however conciliatory the speaker of (l), (2) and (3) may be being with his we subjects, the tenor of the (Tone 1) declaratives, and the firmness of the modal shall have in (3) brook no refusal. The Mode of oral delivery, too, with its markedly repetitive theme pattern and staccato short sentences mostly in monosyllables suggests someone who has to put things simply while issuing orders and instructions. It may be objected that a rifle drill session on a parade ground on the edge of English suburbia by an officer or drill sergeant to some rather less than attentive recruits is what virtually every reader of the poem infers from a first reading, so why not start with that as a given? Mainly because inferences are not 'given' and the way they are inferred is something that stylistics can tell us more about. Register is a concept that Halliday and others have developed to help us account for the relations between the language forms we use and features of the situation in which we use them. There are three aspects to register: Field, Tenor and Mode. As we saw in the last paragraph, we infer information about the Field of the discourse—what is going on—mainly from the lexis and grammar chosen in the ideational function; information about the Tenor, or who is taking part, from choices in the Interpersonal function; and information about the Mode—the role that is being assigned to language in the spoken or written medium—from the Textual choices. Conversely we could say that Ideational options in the lexico-grammar realize the Mode. These semantic options (in transitivity, mood, theme, etc.) are then realized in specific forms, which are then realized as language substance in the sounds we utter or the graphic marks we make on paper. In reconstructing the reading process through interpretive stylistics we should see whether any of the grammatical patterns we have observed in Stanza I occur again in Stanza II and whether these inferences, via Register, that we have drawn about the situation of this discourse are confirmed or altered in any way. STANZA II: Discussion Ideationally we again have a string of three identical processes: clauses (1), (2) and (5) all have a relational identifying verb with a deictic this as identifier and some kind of swivel as identified. Swivel is one of those nouns designating a piece of equipment which derives from a verb and so, in (1) and (2), is sling, a nominalization as class modifier of the head of the nominal group, so in the first three independent clauses there is again a tendency to nominalization. This continues in the first dependent clause (3) where a mental process of perception has an animate perceiver, .you, but a phenomenon involving another grammatical metaphor of nominalization: [17]

[18]

S

P

A

S

P

C

S

P In the further dependent clause (4) the material process are given is fully realized with a beneficiary and a goal, but the passive voice makes possible the deletion of the agent. The relational process of identifying of (1), (2) and (5) shifts to a relational of possession in the dependent clause (6), but with an effect of bathos since it is negative possession. Something like the same cumulative pattern is built up in these clauses as we saw in the first stanza with an ironic counterpoint of lexical content (lower sling swivel, upper sling swivel, piling swivel) which sounds more and more precise, being undercut by the complexity and negativity of the grammatical structures: (1) they have (a) (2) they will get (αβγ),(3) they have not got (αβ). By contrast, the 'other voice' produces a long, coherent and positive clause with material process, agent, goal and circumstances of location. As before, however, the recruit's voice engages in a complex semantic metaphor involving personification (The branches hold), metaphor (hold gestures) and oxymoron (silent eloquent). This is poetic language with a vengeance—the only vengeance the recruits can afford for all those insistently pointed grammatical metaphors. And yet there is a kind of vengeance in the echoing last line (8) which parrots the structure of (6) with a minor phonemic/grammatical shift from second to first person subject. In the Interpersonal function there is a marked shift of persons here, but even in the drill sergeant's voice there is a greater awareness of the recruits' presence as human personalities capable of perception (You will see) and possession (when you are given, you have not got). So the impersonality of This is seems to give way to a degree of recognition: even the most one-sided pedagogical process has to take account of the potential 'alien discourse' of the learners (doesn't it?). As in Stanza I there seems to be a contrast in tone between the two voices. The sergeant's voice is almost entirely monosyllabic and adopts a firm declarative pattern of either (Tone 1) or Tone (1—3—1). The recruit's voice uses longer words, complex consonant clusters that slow down the rate of reading, 4 and again keeps the utterance suspended on two or three tone-groups on (Tone 3) (depending on how you read clause (7)) until it is resolved in the ironic echoes (Tones 3—1) of (8). The irony of this last line is further emphasized by its thematic structure. The rest of the clauses have an unmarked subject-theme (although there is a contrast between the repeated deictic This (is) in (1), (2) and (5) and the nominal group The branches in (7)), but (6) and its echo (8) have a marked string of thematic elements (C—A—S). They also involve the first examples of anaphoric reference (Which, your, you /which, our, we), in contrast to the heavy exophoric reference of the sergeant's demonstration (this ... the). The irony works both ways, of course. Whereas the marked contrast in person (Interpersonal) and the anaphora (Textual) seem to mock the sergeant's earlier utterance, the Ideational fact is that the recruits lack silent, eloquent gestures; their movements are noisy and inarticulate, or unarticulated. This is brought out by the contrast between material process 'Hold' (as the prominent and stressed monosyllabic first word in line 5) and relational:possession [19]

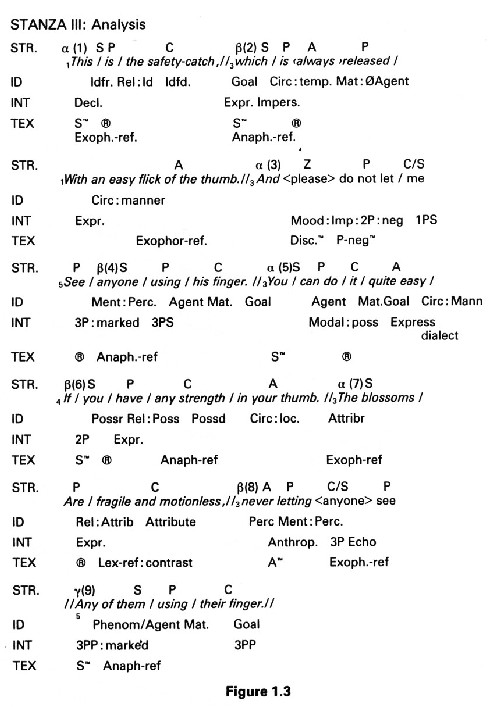

process (colloquial) got (as the prominent and stressed monosyllabic last word of line 6). In all three functions the linguistic choices Reed has made in Stanza II continue the contrasts he set up in Stanza I. Nominalized processes in a tripled structure hammer home the technical lexis, whereas a complex poetic metaphor built around a fully material process in (7) sets up a different world, one which textually and interpersonally mocks the first voice. However, we do seem to find interpersonal hints in (3) and (6) of the sergeant becoming aware of his recruits in a rather limited way. Stanza III may reveal whether this tendency is significant. STANZA III: Discussion We will look in vain for a tripling of types of process in this stanza. It opens with the habitual relational process of identity, and this is in marked contrast to the relational of attribution of the other voice in (7). These form a frame for a sequence of material action processes (which is released (2), anyone using his finger (4), and You can do it (5)). In the drill sergeant's voice there has been a focus on types of action. There is some nominalization in the noun flick (i.e. 'one flicks one's thumb') and in the rank-shifted complement clause (4) (i.e.

P

C/S

P

C

C/S

P

C The material action processes tend now to include a circumstantial adjunct: both time (always) and manner (with an easy flick of the thumb) in (2), and manner (quite easy) in (5). Moreover, these are all marked with a positive expressive quality: the ideational and interpersonal choices are functioning together here to reveal a much more direct engagement on the sergeant's part with the recruits as people. Naturally, this emerges most clearly in the interpersonal choices determined by Tenor: 'cajoling' in (3), 'persuading' in (5), 'reasoning' in (6). Similarly, the marked third person impersonal anyone in (4) shifts to a marked use of second person in (5) and (6). There is also a tendency, as I read it, to use the more dramatically marked tones: (Tone 5) in (4) and (Tone 4) in (6), which with their mood of exhortation or qualification also realize a higher degree of awareness of the interlocutor's possible objections. The main interest in the Textual choices in this stanza is in the rather complex pattern of lexical cohesion. Whereas the thumb-finger-thumb chain of the sergeant stresses movement (flick) in (2) and strength in (6), the direct opposites are foregrounded in the recruit's description of the blossoms— fragile and motionless. This consolidates the opposition between the sergeant's obsession with material action processes and the recruit's awareness of the state of nature. This set of contrasts highlights the irony of the echo in (8)— [20]

(9a) of (3)—(4) and the absurdity of the personification of the blossoms even having, let alone using, their finger. This is absurd, and it makes a total mockery of the sergeant's earlier injunction, but it also suggests something secretive and impenetrable about nature. Perhaps it is this that the recruit identifies with, and this too that the [21]

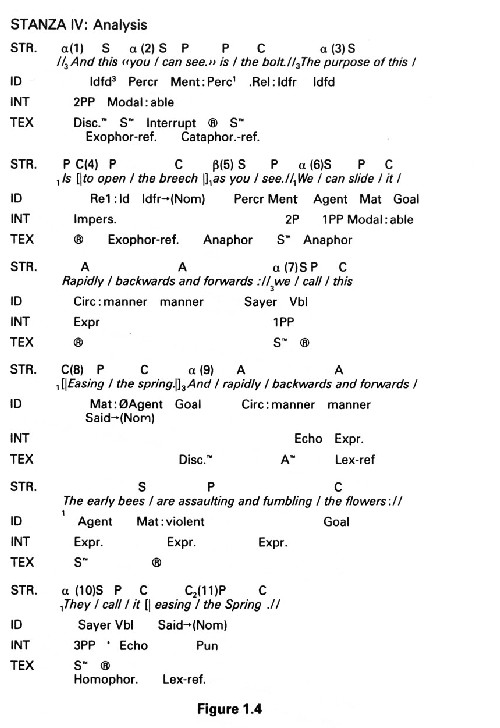

sergeant fears: 'unless you shout at them, they will resort to secretive tricks like using their finger instead of their thumb'. This emerging stress on a furtive alternative world, whether in nature or in the minds of the recruits—or in nature in the minds of the recruits—becomes a major element in the lexico-grammar of Stanza IV. It also becomes the point of the central joke of the poem which depends on a complex interplay of registers. STANZA IV: Discussion The sergeant's voice continues to select primarily relational: identity and material processes (this is the bolt, the purpose of this is to open, we can slide it, easing the spring). Both the identifying clause (3) and the verbal process clause (7) contain as their complements rank-shifted clauses of material action: the tendency to nominalize (by giving a complement role to) material actions continues. The sergeant also continues to name the parts of the rifle in threes (Bolt—breech—spring). However, the mental processes of perception are assigned to you, the recruits, and are almost reassuringly used to interrupt the flow of the demonstration. Once again, the sergeant's consciousness seems to be invaded by the recruits, or his awareness of their inattention. The staccato clause structure, the marked use of the second person pronouns in (2) and (5) and the reminder of his allegiances in the first person plural of (7) mimic the shuttling of his consciousness between his ideational and interpersonal roles: like all teachers, his dilemma is whether to focus more on the field of the subject matter or more on the tenor of his relations with his pupils.5 He is not helped by the fact that all these also mimic the shuttling movement of the bolt in the breech of the rifle, and this appeals to the secret subversive streak in the minds of the pupils. It does not take much to make bored young men undergoing basic army training think of sex (notwithstanding the doses of bromide administered in the cookhouse tea!) and erotic metaphors are everywhere to be found by those in the mood to seek them. Bolt and breeches, innocent enough as parts of a rifle, become perfect metaphors for sexual organs in action when the field shifts, when we get a 'naming of private parts'. This metaphorical shift— or perhaps we should call it a dual-focus, since we remain conscious of both fields at once—then makes possible a further shift into what has been the dominant field in the recruits' consciousness up to now: nature in the spring. The bees now take on a highly transitive role as agents of the material process of assaulting and fumbling the flowers—the first time in the poem that nature has been active at all. Moreover, the processes are nicely ambiguous: the metaphors for pollination combine lexical items with strong connotations of both warfare and sex: assault, basically a military term, is most frequently encountered in the context of rape, and fumbling, the clumsy handling of equipment by untrained hands (say, army recruits), is often used in descriptions of awkward, inexperienced love-making. They call it easing the Spring. The pun on rifle spring/season Spring, foregrounded perhaps a shade too obviously by the capital letter, now [22]

[23]

points in, not two, but four directions: the competent users of rifles literally ease the spring by sliding the bolt and breech: the early bees make Spring's fertility easier by pollinating the flowers; bored army cadets with sex on the brain see the rifle movement as analogous to human acts of fertilization; but all these actions involve violence, violation even. Nature seems to have been injected with the martial propensities of the trained soldier. And who are 'They' in that echoing clause (10)? The bees? People in general? The army? Somebody calls it easing the spring, and easing the spring by any other name would lose all these ambiguities. All this making of metaphors (semantic rather than grammatical) is highly counter-productive to the naming of parts in rifle-drill, however productive it may be of recruits' daydreams and entertaining poetry. However, we cannot ignore the converse process that seems to be taking place in this stanza: nature has become involved in a quasi-military process, and one aspect of nature has been named. The implications of this are developed in Stanza V. STANZA V: Discussion Everything gets recapitulated in this stanza. And what does recapitulation involve? Naming. The stanza is framed by clauses from the end of Stanza IV and the beginning of Stanza I (themselves constituting a frame for the first four stanzas), both of which, as we have seen, involve nominalizations (namings) produced by grammatical metaphors, as shown by the rank-shift brackets around the complement of two very general verbs, call and have. Clauses (3) and (4) sound quite positive with expressive lexical items easy and strength intensified by perfectly and If ... any, but the direct address of second person plural you in the sergeant's voice in Stanza III (following You can do it quite easy) seems to have become the generalized impersonally (following if is perfectly easy) and the transitivity of these clauses has lost its dynamism: the processes are merely relational (attribution in (3), possession in (4)). The five clauses I have just described recapitulate elements, almost verbatim, from Stanzas IV (1) and (2), III (3) and (4) and I (12). And yet a recapitulation is not just a repetition in poetry. Apart from the shift of person we have noted in (3) and (4), the very change of context brings a change of meaning. Clause (10) of Stanza IV was a summation; Clause (1) of Stanza V (with identical words) is a new phase of the argument. Our notation for the intonation is not delicate enough to bring out this distinction, but I find it impossible to read aloud these two 'identical' clauses in the same way. We have now dealt with almost all the major clauses—those carrying a finite verb, hence realizing transitivity and mood—in Stanza V. But the analysis shows a string of three minor clauses (marked 'Z') which are just the names of parts of the rifle we met in Stanza IV: now we are really faced with a mere naming of parts, although the sexual joke is sustained by linking easing the Spring with strength in your thumb with the private parts already noted (bolt and breech) and a new, even more sexually explicit rifle part (the cocking piece). The [24]

adjunct like in (5) is beautifully ambiguous in this respect: on the one hand, it

seems to link the erotic elements; on the other, it seems like that almost empty

particle The other entirely new lexical item in Stanza V is the point of balance—which is beautifully poised at the fulcrum of both the syntactic and the verse [25]

structure of the stanza: we have renamed the rifle parts, now—in a further series of three 'Z' clauses—we will name nature's parts: the almond-blossom is attributed with Silent and the bees with the participle going, but still the ineluctible process of naming seems by the end to have caught up with nature too. Hence the extreme ambiguity of the last line. In its structure and lexical content it recapitulates three clauses from Stanza I: clauses (1), (4) and (6). Yet even they are not the same. The first has no conjunction, the second begins with the discourse adjunct but and repeats to-day, the third begins with And, a highly ambiguous word which could make it part of either the recruit's or the sergeant's voice. Now we have a supposedly explanatory discourse adjunct For. What does it explain though? That finally the obsession with merely naming things has infected the recruits? That nature, earlier describable only through semantic metaphors, has now become nominalizable? Or that perhaps some vestiges of grammatical complexity (the attributes within the 'Z' clauses) save nature from mere naming? Perhaps these questions are not resolvable because of the point of balance, Which in our case we have not got. OVERVIEW We have now completed the functional lexico-grammatical description of the poem. There are clearly aspects of the poem's structure that we are far from having described adequately. Apart from a superficial look at intonation and a mention of monosyllables and consonant clusters, we have said little about the sound patterning. Yet a phonological description that revealed a foregrounding of front vowels in Stanza I; of semi-vowels /w/ and /y/, often in combination with sibilants /s/ and /z/ in II; of nasal consonants in III; and stop consonants in IV might well enrich the evidence we have collected so far. Similarly, in this highly oral, but non-metrical, poem we have not risked entering contemporary controversies about how to describe rhythm in poetry. A feature of the line structure which does relate to rhythm but also interacts powerfully with the grammar is the enjambement. A large proportion of the lines end in the middle of a syntactic unit. In the case of the sergeant's voice, this often serves to isolate and emphasize even more strongly a marked adjunct theme (e.g. in I, Yesterday ... And to-morrow morning ... But to-day). In the case of the recruit's, it emphasizes the interrupting tendency of the 'alien discourse' ('Japonica... The branches... The blossoms'), with the 'normality' of its unmarked subject themes. This tendency, however, is put to the test in IV where the recruit's voice breaks in with three thematized adjuncts (And/ rapidly/backwards and forwards) before we move to the subject theme in the next line. As with most patterns in the poem, this linking of syntactic theme and line-end breaks down in the last stanza where the minor 'Z' clauses 'naming the parts' of both the mechanical world and nature consist only of themes. The recurrent pattern in the verse structure is of three and three-quarter lines of the sergeant's voice, one and a quarter lines of the recruit's voice and a [26]

final line that is ambiguous, but seems to be the recruit ironically mimicking the sergeant. The first quarter-line (end of line 4) of the recruit's voice seems to interrupt the flow of the sergeant's voice, replacing the staccato rhythms, short clauses, tripling structures with slower rhythm, longer clauses and tone-groups, and a single structure. This interruption comes much earlier in Stanza IV where the recruit's voice 'invades' the other after only a quarter of a line, although, as we have seen, by this time on the semantic level the rapid and multiple actions seem to have invaded nature. In the last stanza the point of balance occurs precisely half-way—across the third line-end—and both voices are doing the same thing: naming parts. The most obvious thing to emerge from our lexico-grammatical and structural analysis so far is that there are two registers interacting with each other—and that is the most obvious thing one can say about the poem. So what has been gained? The concept of Register is an explicit and coherent way of connecting formal linguistic choices to the situational context in which they are chosen. It makes it possible to generalize from pure levels of description, whether grammatical, phonological, metrical, verse-structural, etc., to a kind of meta-description. We could list the contrasts between the two registers in terms of their Field, Tenor and Mode as follows:

These semiotic orientations are realized in the grammatical systems and lexical choices of the Ideational Function, as we have seen, by:

The realizations here are readily recognized in choices of mood, intonation, neutral or attitudinally marked lexis and patterns of mimicry. Perhaps, too, Constricted/lax voice. [27]

The first aspect of Tenor may need some explanation. Register points 'downwards' to lexico-grammatical choices, but 'upwards' to social relations of power and ideological determination. One linguistic feature we have neglected so far is the dialect usage (Cockney and many regional dialects) that spans the 3—4 lines of Stanza III—the very centre (or point of balance?) of the poem: You can do it quite easy / If you have any strength in your thumb. This motivates many readers of the poem (including me) to read the poem aloud with a Cockney dialect for the sergeant's voice. For those brought up on the English lyric tradition it is hard not to read the other voice in the Received Pronunciation of BBC/Oxford English. As Halliday has shown, however, there is often a strong social relationship between register and dialect (Halliday 1978: 8—35): particular social classes (partly recognizable by their dialect) tend to choose (or be landed with) work requiring specialized registers. The 'stage sergeant major' (and every sergeant or petty officer I have met) is a case in point. This might not be significant for the poem except for the echo of this utterance at an equally crucial point, between lines 1 and 2 of Stanza V. Here the recruit not only mimics the sergeant, but corrects his English: it is perfectly easy /If you have any strength in your thumb. The recruits are better educated, think in poetic metaphors and care about nature: probably the sergeant's nightmare, university graduates. Apart from the interplay of the fields of rifle drill and the contemplation of nature; apart from the opposed roles of teacher and taught (or unteachable), there seems to be an opposition between the institutionalized, but temporary and artificial, power of army rank and what a certain English ideology views as the 'natural' superiority of class. In the end the recruits have the strongest sanctions against their subordination: their command of language allows them both inattention and insubordination. Except for this small dialect detail and its echo, this is not something that can be pinned down very precisely at the lexico-grammatical level. It pervades the poem if we read it in a certain way. This brings us to what follows the 'naming of parts' in stylistics, our initial question. It must be clear by now that even when we are analysing the linguistic choices in detail stanza-by-stanza we cannot—and should not—avoid generalizing statements that point both to the development of a theme within the poem and to wider connections and connotations in the world outside it. We have now reached the stage of the 'hermeneutic spiral' where we seek a synthesizing explanation. We will not close off the spiral by tying ourselves to only one such explanation: we will still want to test it against the details we have been naming to see how well it works, and we will remain open in subsequent readings or in discussions with others to different interpretations. We all bring to a poem, as to any discourse, our own 'social semiotic'. I have suggested that 'Naming of Parts' seems to fracture the world through a sort of compulsive, institutionalized act of naming, so that even nature's harmony [28]

and integration is reduced by Stanza V to a mere list of features—the danger stylistic analysts run of finding 'the facts but not the phosphorescence', as Emily Dickinson put it. Let me mention two other related but distinctive interpretations governed by a different social semiotic. A group of Japanese teachers of English with whom I discussed the poem identified instantly with Japonica, coral, almond blossom and bees and saw the poem as a dialogue of conflict between the rational positivism of the West, obsessed with time, with naming, with scientific procedures, with technology and with war, contrasted with the contemplative East, concerned with the direct, unmediated perception of reality in a holistic, integrated fashion. An artist friend of mine is convinced that good drawing and painting involves mainly the right hemisphere of the brain, which is concerned with the direct perception of spatial relations, rather than the linear, analytical, language-governed operations of the left hemisphere. His truly schizophrenic interpretation of 'Naming of Parts' sees it as a battle between the two hemispheres. We can pick our own scale of interpretation: either the global hemispheres or the cranial hemispheres, or somewhere in between! Like Henry Reed's pun on spring/Spring and the sexual double entendres of the poem, that last little joke of mine may not have been very funny, but it was a kind of meta-statement. It reveals a pattern of patterns. But the Japanese interpretation and my artist friend's interpretation were also meta-statements. They revealed a pattern in the comparison between the pattern of language and thought set up by the sergeant's voice and that set up by the recruit's voice. Most of this paper has been concerned with the description of the patterns, stanza-by-stanza and clause-by-clause, within each of the voices. I believe that Gregory Bateson has described very clearly the relation between the different levels of a stylistician's work in his wise and stimulating book, Mind and Nature. He says there are three levels or logical types of descriptive propositions:

1. The parts of any member of Creatura are to be compared with other parts of the

same individual to give first-order connections. Later in his book Bateson says: We should be taught about the pattern which connects: that all communication necessitates context, that without context, there is no meaning, and that contexts confer meaning because there is a classification of contexts ... Anatomy must contain an analogue of grammar because all anatomy is a transform of message material, which must be contextually shaped. And contextual shaping is only another term for grammar ... I hold to the presupposition that our loss of sense of aesthetic unity was, quite simply, an epistemological mistake.8 [ibid.: 28] [29]

Perhaps we most need poets to correct that epistemological mistake by their knowing creation of the pattern of patterns'. And perhaps we can come near to doing them justice if we try to distinguish clearly between our own levels of description and the meta-pattern by which we connect them. NOTES

1. Following Leo Spitzer, the more conventional term for this shuttling process

between intuition and description is 'the hermeneutic circle' (see Spitzer 1948).

However, I very much prefer the open-ended and (hopefully) upwardly striving

image of a 'hermeneutic spiral'. [30]

|

Page last modified: 01 October 2016