The Concise Enclyclopædia of Modern World Literature (50s.), edited by Geoffrey Grigson, which includes more than 300 articles on individual authors, and—to place them in their wider setting—articles describing the development of the major national literatures and characteristic literary forms of our time...[.]

The contributors... were asked 'to write about what they had enjoyed, communicating their enjoyment without escaping into superlatives'. There is a complete author/title index, and general bibliographies. There are 16 pages of colour plates, 160 in half-tone.

The contributors... were asked 'to write about what they had enjoyed, communicating their enjoyment without escaping into superlatives'. There is a complete author/title index, and general bibliographies. There are 16 pages of colour plates, 160 in half-tone.

The London edition being prohibitively distant, I settled for a copy of the American edition of Grigson's Encyclopedia (New York: Hawthorn, 1963), just a short drive away, at a local public library:

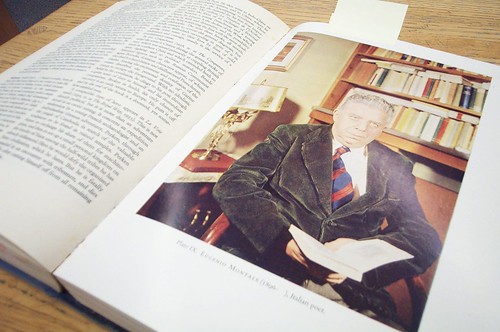

It's a beautiful book. Or, at least, it was beautiful in 1963. The reference copy I looked at had been ridden hard: the binding was torn and held together with book tape; the pages brittle and split on some edges. But the endsheets were still bright and colorful, and the entries lavishly illustrated (for an encyclopedia) with photographs, some of which I had never seen, including a picture of Louis MacNeice attending Dylan Thomas' funeral. Some thoughtful cataloger had even pasted the original front and back flaps of the missing dust jacket inside the front cover.

In his editor's Introduction, Grigson explains his instructions to the contributors:

Some writers — or some individual books — need rescuing from what is almost or entirely oblivion. Some have escaped attention because they are not easy to categorize.

Bearing this in mind that 'literature' is not really so common, in spite of publisher's advertisements, contributors to this volume were asked to write about what they enjoyed, they were asked to communicate, in a level way, their enjoyment; and to avoid, in doing so, both superlatives and the various ways of evading literature. One way of our time is historical, so they were asked not to indulge in chatter about trends, influences, schools, traditions. They were asked for sensible dogmatism — at any rate, for the unequivocal statement, and (where space allowed) for quotation — i.e., some part of the substance of what they were writing about. Another way of evasion is biographical. They were asked to concentrate on the books of each author, not on his life (though a biographical fact may be relevant, Yeats, for example dreaming of Bernard Shaw as a sewing machine which smiled and smiled). Even then, contributors were asked to concentrate on the books which mattered, instead of giving the neutral itemized survey which you might expect from a conventional encyclopedia.

Bearing this in mind that 'literature' is not really so common, in spite of publisher's advertisements, contributors to this volume were asked to write about what they enjoyed, they were asked to communicate, in a level way, their enjoyment; and to avoid, in doing so, both superlatives and the various ways of evading literature. One way of our time is historical, so they were asked not to indulge in chatter about trends, influences, schools, traditions. They were asked for sensible dogmatism — at any rate, for the unequivocal statement, and (where space allowed) for quotation — i.e., some part of the substance of what they were writing about. Another way of evasion is biographical. They were asked to concentrate on the books of each author, not on his life (though a biographical fact may be relevant, Yeats, for example dreaming of Bernard Shaw as a sewing machine which smiled and smiled). Even then, contributors were asked to concentrate on the books which mattered, instead of giving the neutral itemized survey which you might expect from a conventional encyclopedia.

(p. 11)

(Yeats apparently had some difficulty digesting Shaw's Arms and the Man [1894]: 'Presently I had a nightmare that I was haunted by a sewing-machine, that clicked and shone, but the incredible thing was that the machine smiled, smiled perpetually.')

Alas, although there is a full list of all the contributors at the front of the volume—and biographical notes on them at the back—the articles in the encyclopedia are not signed. So we must take Grigson's instructions to heart, and ask ourselves, "Whom did Henry Reed enjoy? Who was Reed uniquely suited to concentrate on and communicate about?"

I made copies of the most likely suspects: Ugo Betti, almost certainly; Thomas Hardy, unequivocally; Montale and Montherlant, possibly; Pirandello? Maybe.

Update: After looking at my scans (linked above), Ed (of I Witness) feels strongly that the Hardy article is not Reed's (and I must reluctantly agree). But Ed thinks that the Betti is a possibility, and Montale, likely. Thanks, Ed!