|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

Posts from March 2008

|

|

|

27.4.2024

|

"Weird" Al Yankovic has an excellent song, "Bob," which is not simply a parody of Bob Dylan's "Subterranean Homesick Blues," but also an intelligent exercise in palindromes. The music video (YouTube) for "Bob" is a faithful re-creation of the opening sequence to the 1967 Dylan documentary by D.A. Pennebaker, Don't Look Back.

All this reminded me of a promotional gizmo which came out for the release of the Dylan retrospective on CD last year, which we will now use for our own purposes to summarize Henry Reed's poem, " Chard Whitlow," in ten cue cards or less:

"Chard Whitlow" is itself a parody of T.S. Eliot's Four Quartets, so the circle of life and satire is now complete.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

As afforded me by my time spent working a half-day on Easter Sunday, I was able to sneak out of the last couple of hours of work today, and managed to do something resembling genuine scholarship. There was a book on campus, in the library's Special Collections, which I had discovered hiding in plain sight on Professor Goethal's " Poetry & WW2" page: Poets in a War, by Kenneth A. Lohf (New York: Grolier Club, 1995). The book is a detailed catalog of an exhibition curated by Mr. Lohf, which was displayed at the Grolier Club of New York from December, 1995 through mid-February, 1996.

The Grolier Club is 'America's oldest and largest society for bibliophiles and enthusiasts in the graphic arts' (they are currently showing an autograph manuscript of Robert Burns' " Auld Lang Syne"). From the Club's webpage for Poets in a War:

In observance of the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, the Grolier Club in December 1995 presented an exhibition featuring manuscripts, first editions, drawings and portraits of 130 British poets of the 1940s who served on the battlefronts and home front.

The book is lavishly illustrated with photographs and reproductions, and I was hopeful that it might contain a picture of Reed. Alas, no such luck, though there is a reproduction of the title page of Reed's 1970 collection, Lessons of the War (New York: Chilmark Press). The text does contains detailed bibliographic information on the Lessons and A Map of Verona (London: Jonathan Cape, 1946), as well as several appraisals of Reed's poetry:

Of the poets who produced one or more memorable poems, F.T. Prince's 'Soldier's Bathing' and Henry Reed's 'Naming of Parts' (the first part of his series of poems, 'Lessons of the War'), stand out because of the ways in which they treated their specific subjects...[.] Like Prince, Reed, who after a year in the Army worked at the Foreign Office for the remainder of the war, had written only one volume of poetry, A Map of Verona (1946), by the time the war ended...[.] Though his participation in the army was brief, his series of poems 'The Lessons of War,' [sic] collected in A Map of Verona, is among the best-known group of poems of the Second World War. Like 'Soldier's Bathing,' 'Naming of Parts,' the first poem in the series, is a meditative poem in which the central conflict is between a recruit's wandering thoughts and an army officer's emotionless voice of instruction in the use of a rifle, a voice with a decided sexual dimension which is lost on the recruit who thinks solely of the beauty and sensuousness of nature. It is the human scale of these poems—both of their speakers are soldiers—that facilitates our understanding of the meaning of war to the men caught in its turmoil. (p. 26)

The library's copy appeared to be in pristine condition, or at least it had been previously handled with the greatest care. I was loathe to ask for photocopies since it would involve putting pressure on the books' virgin spine, so I settled for copying out the relevant passages in longhand, and taking pictures of everything, in case I made any mistakes (more pics on the Reeding Lessons Flickr page). An hour well spent!

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

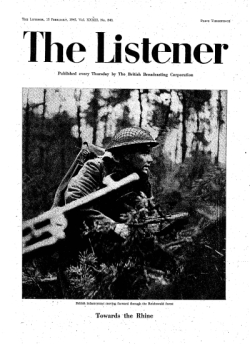

[This is the final letter to the editor regarding two articles appearing in the BBC's Listener in January, 1945, written by Henry Reed: " Poetry in War Time: I—The Older Poets," and " Poetry in War Time: II—The Younger Poets." Here, you may read the entire, nine-part " Points from Letters" saga. This is the last. A final reply from Mr. William Bliss.]

The Listener, 29 March, 1945. Vol. XXXIII. No. 846 (p. 353) [.pdf]

Poetry in War Time

Mr. Reed flatters us. I do not think that either I or Mr. Richards could give him points in the non sequitur handicap. And, unawed by his somewhat superior reproof, I must still maintain that he did, most clearly, say and not merely suggest, that good poets had lacked appreciation in the past. There is his letter. I have just looked at it again. He speaks of 'the perennial absurdity of the contemporary'. He says that it 'is no new thing', but that Tennyson and Wordsworth and Coleridge and Keats were belittled or 'coldly received' and he feels quite sure that Shakespeare would have been thought 'uncouth' by those brought up on Marlowe: And he clinches these statements by his 'one only' reason, viz., 'the interadicable human belief that only the dead are harmless and praiseworthy'.

There is nothing here about 'a vociferous subcurrent of criticism' (whatever strange sort of noisy silence that may be). It is perennial and universal, 'an ineradicable human belief that, only the dead are praiseworthy'. Now, the modern poets whom Mr. Richards and Major Hunter and I fail to appreciate are, I believe, still alive. Very well then—sequitur—? Now, in his last letter, Mr. Reed agrees that good poets are appreciated in their lifetimes. But it does not follow that all poets who gain applause or have a following in their lives are good poets. The age that produced Dryden also produced Shadwell, who 'never deviated into sense'. The age that produced Pope also produced Colley Cibber and the other even less admirable heroes of the Dunciad. The age that produced Keats also produced Thomas Haines Bayley. The age that produced Byron also produced 'hoarse Fitzgerald' of the 'creaking couplets'—and so on. Mr. Reed need only consider the list of Poets Laureate from Pye to Alfred Austin to see that Messrs. Eliot and Auden and Pound are not safe yet. For all these forgotten versifiers were admired during their lives. All had a following.

But it is neither the gallery nor the select few who, in each generation, applaud new things just because they are new or to show their own superior eclecticism, who are the final arbiters. It is Time—and the consensus of opinion of all lovers of poetry, that is to say all human people. And we've got to wait for that. Securus judicat orbis terrarum—and I don't want to hedge that bet.

Lane EndWilliam Bliss

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

[Here, at last, is Henry Reed's final word in these matters, though it seems nothing has been settled to anyone's satisfaction. What began as two articles on "Poetry in War-Time," written for The Listener in January 1945, resulted in a lengthy exchange of letters and a debate over the difference between traditional and modern verse. Joining the fray today is the poet and journalist, Allan M. Laing. Part 9 and the conclusion is next.]

The Listener, 22 March, 1945. Vol. XXXIII. No. 845 (p. 324) [.pdf]

Poetry in War Time

I have nothing to add to this discussion except a few words of protest at the attempts of Mr. Richards and Mr. Bliss to credit other people with as great a talent in the non sequitur as their own. I did not suggest that good poets had lacked appreciation in the past (nor do they now). What I did suggest was that there has always been a vociferous sub-current of criticism which hates the contemporary; and that that tradition is maintained by Mr. Richards, Major Hunter and Mr. Bliss. And I should be the last to suggest that such -voices infiuence public appraisal very much, even in their own time. But if they ask questions, one must attempt to answer them, even if they will not—dare I quote?—'stay for an answer'.

BletchleyHenry Reed

The passion for obscurity, which prevents so much modern verse from being poetry, is a perennial problem, and the criticism of it current today may be matched from the distant past. In 1646, François Maynard, a French poet, published an epigram addressed to a contemporary writer, which may be Englished as follows:The sense of what you write

Lies locked behind close bars:

Your language is a night

Lacking the moon and stars.

My friend, your garden weed

Of this dark mystic strain:

Your works at present need

A god to make them plain.

If you wish to conceal

The beauties of your mind,

How odd you do not feel

Silence to be more kind! Could a wiser admonition be addressed to the authors of some of the verse we are expected to understand in Horizon, New Writing, etc.?

LiverpoolAllan M. Laing

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

I have had, on occasion, the pleasure of using and perusing the website of Helen Goethals, Professor of English at the University Lumière Lyon 2. Professor Goethals is "interested in poetry and war during the twentieth century," and has several excellent pages devoted to the poets of the Second World War, including a select bibliography and filmography. She even refers to "Naming of Parts" as 'the most famous poem to have come out of the war'.

As a sort of tangent in my hunt for Henry Reed material, I've been reviewing items from the period which ask (or answer) the question, " Where are the war poets?", which came as a lament that no Brooke or Owen or Sassoon was seen to emerge from World War II. So it was with interest that I noted several references in Professor's Goethal's conference papers that the famous question was even raised in Britain's Parliament: in " Talking to India: George Orwell, the BBC, and British Policy Towards the Indian Empire During the Second World War" ( n13), " Philip Larkin and the Poetics of Resistance to the Second World War" ( n15, collected in Philip Larkin and the Poetics of Resistance [Andrew McKeown and Charles Holdefer, eds. Paris: L'Harmattan: 2006]), and " The Muse that Failed: Poetry and Patriotism During the Second World War" (appears in The Oxford Handbook of British and Irish War Poetry [Tim Kendall, ed. London: Oxford, 2007]).

So I was quite surprised when I went to the Parliamentary Debates for June 13, 1940, and discovered that the question raised in the House of Commons was not so much the rhetorical "Where are our war poets?", but the much more literal, "Do you know where Messrs. Auden and Isherwood have got to?"

The question, of course, was what to do about British men of required registration age (between 18 and 41 years old, according to the National Service [Armed Forces] Act of September 3, 1939), who were abroad either by choice or necessity. W.H. Auden had emigrated with Isherwood to New York City in 1939, was 33 years old in 1940, and became a U.S. citizen in 1946.

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

- Voices in Wartime (DVD). An acclaimed feature-length documentary on the experience of war through the words of poets, soldiers, journalists, historians and experts on combat from around the world.

- Great Poets of the 20th Century (The Guardian). Brings together seven of the greatest poets of the 20th century: Sassoon, Heaney, Hughes, Larkin, Plath, Auden, and Eliot.

- Found: The Secrets of the Little Prince Still Alive (The Independent). Christopher Fletcher re-discovers the personal papers of the poet, critic, and editor, Tambimuttu (1915-1983):

After a three-month sojourn in the blast freezer (it does for the insects), I spread the papers out in the vaults of the greatest research library in the world. There, fixed together with rusting pins and clips, occasionally riddled with pest holes but otherwise intact, lay the substantial remains of a decade's worth of literary endeavour; a decade in which Tambi had issued 14 editions of Poetry London magazine and over 60 books of poetry and prose, often exquisitely illustrated by up and coming artists. Here was something wonderfully—almost spookily—hermetic, beginning in 1938 as soon as Tambi arrived in London, and ending in 1949, on the very eve of his departure.

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

[This is where, in my opinion, the old guard's arguments break down. For here, Mr. William Bliss joins in—and is willing to bet money, no less—that the words of Eliot, Auden, and Pound will fade with time; Mr. Richards replies yet again, to call Dadaism, Futurism, Surrealism, atonality, and functionalism 'freakish and crazy cults' (though Reed may have sided with him). Worst of all, Richards uses in his defense my favorite poet who never existed: Ern Malley. At least Mr. Bliss, Mr. Richards, and Reed can all agree on one thing: Keats got a bum review from The Quarterly.]

The Listener, 15 March, 1945. Vol. XXXIII. No. 844 (p. 299) [.pdf]

Poetry in War Time

I do not see what 'reasons' Mr. Henry Reed can expect anyone to give who finds modern poetry to be uninspired, ungifted, shapeless, etc. If I say a pudding is heavy and has no currants in it I cannot give any 'reasons'. There is the pudding.

But when Mr. Reed gives us his 'one only' reason he simply misstates the facts. The 'perennial absurdity of the contemporary' is a figment of his imagination. Most great poets have enjoyed considerable appreciation in their lifetime. Tennyson certainly did, whatever 'Q's' grandfather may have thought. There is a great deal to show that the 'Lyrical Ballads' were not coldly received. Even Keats, though he died so young, lived to see himself acclaimed. (The Quarterly's rude remark, by the way, was only about 'Endymion';1 Blackwood's2 was much worse; but reviewers were then notoriously conservative.) And Mr. Reed's assumption about Shakespeare and Marlowe is just an assumption. Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden, Pope, Shelley, Swinburne, Tennyson, Browning—even George Meredith, all were popular in their lives. (And Mr. George Bernard Shaw isn't doing so badly!)

No. So far from its being 'only the dead who are harmless and praiseworthy', it is always the immediately dead who are forgotten or belittled and (if they be truly great) have to wait for one or two or even more generations to come finally into their own.

Neither Mr. Reed nor I therefore will know for sure which of us is right, though I would be willing to make a small bet about it and deposit the stake with the Curator of the British Museum for the benefit of my great-grandchildren. If I were Mr. Eliot or Mr. Auden or Mr. Ezra Pound I shouldn't feel very sure of immortality—or, being a modern poet, should I?

Lane EndWilliam Bliss

When Mr. Reed writes 'I believe pattern, form and finish to be only part of poetry; to put them at their highest the are only co-equal with what poetry has to say', I cannot forbear to say I agree. Not quite, however, in the way he means those last six words. Change say to convey and there perhaps is the kernel of the difference. I read Brooke's immortal five sonnets again and I realise afresh as the great lines roll on that it is not tidiness but the movement and swell in words that makes them poetry. But if the pulse and heart-beat is there, there is already that necessary fusion between logical sense and form (in this case metre) which is the miracle of poetry.

The Quarterly3 fell foul of Keats, finding no 'meaning' in 'Endymion'. This merely illustrates the complete destructive critical irresponsibility of those times. Nowadays, the irresponsibility takes the form of literally illimitable gullibility—witness the 'Angry Penguins' and 'Ern Malley' [ernmalley.com], an affair that isn't laughed off yet by any means. Then there was the gentleman who returned Keats' first collected volume to the bookseller's protesting it was 'little better than a take-in'. Where does this form of argument get you? 'They were wrong about Keats, Bizet, Wagner, Ibsen and Manet—therefore they are wrong about us'. Non sequitur. Queen Victoria, Mr. Gladstone, Ellen Terry and even Swinburne were devoted admirers of Marie Corelli [Wikipedia]. Contemporary verdicts have to be revised both upwards and downwards but in the main, surely, are confirmed.

'The Muse has withdrawn'. That, says Mr. Reed, is the perennial cry of the dyspeptic laudator temporis acti [praiser of past times] impatient with the contemporary young. For Mr. Reed there has been no climacteric, no fundamental break, whereas for me self-evidently there has. Does it really count for nothing that in our time we have seen such freakish and crazy cults as dadaism, futurism, surrealism, atonality in music and functionalism in architecture? You cannot connive at functionalism in one art and decry it in another and, functionally speaking, the Ministry of Food's weekly Food Facts [WWII Ex-RAF] are masterpieces of English prose.

PooleGeorge Richards 1, 3 John Wilson Croker. Review of Endymion: A Poetic Romance, by John Keats. The Quarterly Review 19, no. 37 (April 1818) 204-208.

2 John Gibson Lockhart. Review of Endymion: A Poetic Romance, by John Keats. Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine 3 (August 1818) 519-524.

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

[In which Henry Reed continues the defense of his criticism of Rupert Brooke's namby-pambier poems, and rails against those who blindly dismiss modern poetry, written by soldiers or not (and contemporary or not). This, the sixth part in a series of letters written to the BBC's Listener between January and March, 1945.]

The Listener, 8 March, 1945. Vol. XXXIII. No. 843 (p. 271) [.pdf]

Poetry in War Time

Rupert Brooke's romantic view of war was not the reason I gave for denying him 'any particular poetic merit'. It was the reason, I suggested, for his popularity. Mr. Richards has, however, lost sight of what he first wrote to ask. He is now, with Major Hunter, out in the open, developing a broader and more familiar theme: that modern poetry is, for the most part, uninspired, ungifted, shapeless, formless, artificial, adolescent and as often as not hysterical. The Muse has withdrawn herself. Reasons? None.

Nor indeed have Major Hunter's and Mr. Richards's predecessors in past centuries ever been able to suggest a reason for the perennial absurdity of the contemporary. For it must not be thought that it is a new situation they are deploring. 'Q's' [Arthur Quiller-Couch (Bartleby.com)] grandfather, reading a poem of Tennyson, described it as 'prolix and modern'. There is nothing to show that years earlier the Lyrical Ballads of Wordsworth and Coleridge were less coldly received. We know what the Quarterly thought of Keats. And it is inconceivable that to the conservative the later versification of Shakespeare can have seemed uncouth to those brought up on Marlowe. One cannot unconvince this point of view; one can only point out that it is immemorial. Reasons? One only: that it is an ineradicable human belief (so great is our fear of the creative) that only the dead are harmless and praiseworthy. Is it insignificant that Mr. Richards selects for a meagre praise only Keyes and Lewis from among those I wrote about; and that those two poets are the only ones who are dead?

There is only one other point I wish to refer to: when Major Hunter and Mr. Richards demand 'finish', they are not really disagreeing with me, as they will see if they can bear the to re-read the second of my articles. There are, however, different opinions as to what constitutes finish, and I am arrogant enough to believe I can usually distinguish between the bitterly-achieved artistry of the true poet (however original), and the glibness of the pasticheur; and impolite enough to doubt if, judging from their admiration for Brooke, they can. I must add that I believe 'pattern, form and finish' to be only part of poetry; to put them at their highest they are only co-equal with what poetry has to say. I do not believe, with Major Hunter, that 'to turn a commonplace sentimentality into poetry is the mark of a poet'; I believe that sentimentality and commonplace will corrupt even the brightest gifts, and that, setting aside the charm of light verse, the best poetry is the repository, not of platitude and banality, but of wisdom.

May I be allowed to add that since writing my last letter I have read the American edition of Mr. Auden's verse and prose commentary on 'The Tempest',1 and that I share almost all of Mr. Geoffrey Grigson's warm and understandable enthusiasm for it?

BletchleyHenry Reed 1 For the Time Being (New York: Random House, 1944). Reed would eventually review the London edition for The Penguin New Writing, as "W.H. Auden in America" (Vol. 31, 1947).

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

[A doubleheader to start off March, 1945. On the first of that month, The Listener published two letters regarding Henry Reed's "Poetry in War-Time" articles from January of that year: a vehement refutation by Mr. George Richards of Reed's response to his first letter; and in addition, a letter from the Mumbaikar novelist and poet, Fredoon Kabraji, opposing N.C. Hunter's letter from the preceding week.]

The Listener, 1 March, 1945. Vol. XXXIII. No. 842 (p. 243) [.pdf]

Poetry in War Time

Mr. Reed is of course entitled to his tastes. It is only natural that he should account for my distaste for the typical modern poet on the assumption that the fault is not in him that he is precious, esoteric and artistically embryonic but in me that I am a philistine—'and proud of it'. Indeed, after a duly appreciative reading of his succulent letter I would say I revel in the attribution from such a critic. So 'Rupert Brooke's talents were of the slightest'. His five war-sonnets 'show a defect of imagination which in a poet is serious to the point of catastrophe'. Now we know! After this, to call Mr. Reed a prig would be insipid. I prefer to say instead that I believe these and other passages in Mr. Reed's latter will survive as classics of the Higher (literary) Criticism.

But Mr. Reed is wrong. I am not a philistine, but, rather, a Finishtine. That is I believe that there is no true creation without toil and torment, that the activity indulged in by the miscalled poets of today (the fashionable ones, that is) lacks the afflatus [divine inspiration] and is essentially uncreative, that this modern poetry is by any serious artistic standards of former times a great sham, a prodigious bubble and a naive hoax. I believe, in short, in a rather old-fashioned way that art of all kinds is a matter of pattern, form and finish, not the noise made by an aggrieved and bewildered adolescent trying to get something off his chest. Even in the case of the most sincere, serious, interesting and gifted of these modern poets such as Keyes and Alun Lewis, I would say that the poets of an older day began where these leave off. It is true that many modern poets do not, superficially, lack form but it is imposed, inorganic. Specifically modern poems are of two kinds: (a) cerebral word-jugglings or acrostics, and (b) the result of a feeling in the young poet-impressionist that 'there is a poem there'. The poet of the older generation knew that he had to write it.

Most instructive of all is the reason Mr. Reed gives for denying Brooke 'any particular poetic merit', namely that he took a romantic view of war, unlike other poets who 'saw what war was really like'. One must give Mr. Reed full marks for the uncompromising honesty of his views, but could anything be more crude than this confusion of point of view with power and quality of utterance in expressing it? If to Brooke 'death in battle appeared lovely', it was perhaps from Homer, Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Burns, Campbell, Browning or Tennyson that he got the eccentric idea. In any case poets are not war correspondents but immortalisers of moods. That fine and true critic Earle Welby put the point definitively thus: 'The question with a poet must always be of what value his thought is to him, not to us. Philosophically it may be almost worthless: if it can call into vivid activity his peculiar powers, it will possess the only kind of value we can rightly attach to thought in poetry.'

PooleGeorge Richards

There is too much high falutin' talk about the responsibility of the poet to society. If, in his art, a poet is to be responsible to society at all, he must be wholly himself, i.e., completely irresponsible: with something of the spirit and moods of Pan, St. Paul, J. M. Barrie and Charlie Chaplin allowed free play to be juxtaposed—to blow as the spirit listeth, i.e., exactly as he may be inspired. The only condition on that society must make is that its poet sings: not necessarily in metres and rhymes, but in cadences and rhythms; that his meaning or message is magic not logic, politics or metaphysics; that it is a thing of beauty and abandon like 'Kubla Khan' or 'The Ancient Mariner', nor a pundit's dissertation or a doctor's prescription. Edwin Muir, Vernon Watkins, Norman Nicholson, Henry Treece, Clifford Dyment, Lieutenant Popham have some of this music and magic: and the vogue is all for a return to metrical and even rhymed forms, contrary to Mr. Hunter's impression.

HampsteadFredoon Kabraji

|

1529. Sackville-West, Vita. "Seething Brain." Observer (London), 5 May 1946, 3.

Vita Sackville-West speaks admirably of Reed's poetry, and was personally 'taken with the poem called "Lives," which seemed to express so admirably Mr. Reed's sense of the elusiveness as well as the continuity of life.'

|

All my money is currently tied up in photocopy cards:

|

1528. Manning, Hugo. "Recent Verse." Books of the Day, Guardian (Manchester), 31 July 1946, 3.

Manning feels that 'Mr. Reed has worn thin much of his genuine talent in this direction by too much self-inflicted censorship.'

|

[In this, the fourth installment in an exchange of letters to The Listener, Mr. N.C. Hunter attempts to intercede as the voice of reason in an argument about modern poetry which has been rapidly descending into name-calling and thinly-veiled insults. I suspect this may be the playwright N.C. Hunter (1908-1971), known as 'the English Chekhov' of his day, among whose credits are Waters of the Moon, A Touch of the Sun, The Tulip Tree, and (ironically) the film, Poison Pen.]

The Listener, 22 February, 1945. Vol. XXXIII. No. 841 (p. 213) [.pdf]

Poetry in War Time

In his interesting reply to Mr. Richards, Mr. Henry Reed claims that the 'homme moyen esthétique' approaches modern poetry with tolerance, patience and curiosity. Mr. Richards who, says Mr. Reed, does not, is therefore to be numbered among the Philistines.

It seems to me that this sad relegation gives us a good clue to the nature of modern poetry. We must have tolerance; we must not fling the book aside because it lacks rhyme and metre, or because its meaning is not clear. We must have patience in unravelling its mysteries, and curiosity in seeking out its allusions. In other words, modern poetry must be studied seriously, almost scientifically, and not read as if it existed simply to please and charm and excite.

I wonder if Mr. Henry Reed has put his finger on something that separates modern poetry from a great many of its potential readers? In poetry, alas, cleverness, sensitiveness erudition, honesty—and nobody would deny these qualities to the moderns—are not enough. Mr. Reed claims that Rupert Brooke owed his popularity to his ability to 'falsify the nature of war in a way that the public found palatable'. Is this the whole, or even half the truth? Was it not rather that he happened also to be possessed of that gift for poetic expression which so many of the moderns, however right-thinking, serious and industrious, lack? One might charge Shakespeare with 'falsifying the nature of war' in 'Henry the Fifth', but would that make him less of a poet? And, after all, does Rupert Brooke's popularity rest on his war poetry?

'He wrote in enthusiastic ignorance', says Mr. Reed. Perhaps. I cannot avoid the unworthy reflection that it would be no bad thing to have a little more enthusiastic ignorance in our poetry today—and a little more poetry. Surely it is a mistake to suppose that a poet must necessarily be clever and honest, and that his ideas on war (or anything else) must be sound or profound. What matters is that he should be a poet, and this, whether one likes it or not, Rupert Brooke undoubtedly was. Mr. Reed says that 'there is no fundamental difference between his war poetry and the modern song beginning "There'll always be an England"'. Exactly. To turn a commonplace sentimentality into poetry is the mark of a poet, and English poets from Chaucer to Housman have done it successfully. The brutal fact is that Providence is all too shy about bestowing the gift of poetic genius, and that is why there are so very many modern poets—all sincere, thoughtful, clever and industrious to a man—and so very little poetry.

WorthingN.C. Hunter

|

1527. Rosenthal, M.L. "Experience and Poetry." Herald Tribune Weekly Book Review (New York), 17 October 1948, 28.

Rosenthal says Reed shares with Laurie Lee 'that unhappy vice of young intellectuals—a certain blandness of which the ever-simple irony is a symptom.'

|

[This letter to the editor, by the poet and critic Henry Reed, is part of an exchange between readers of The Listener from early 1945, in response to a series of articles Reed had written on contemporary war poets. It's interesting to note that Reed's address is given as "Bletchley", Milton Keynes, since at this time he was still stationed at the Bletchley Park estate, working for the codebreaking effort as a translator of Italian and Japanese.]

The Listener, 15 February, 1945. Vol. XXXIII. No. 840 (p. 185) [.pdf]

Poetry in War Time

The literary critic must concern himself more with the achievement of poets than with their renown, and the popularity or otherwise of the poets I wrote about is not my business. It is always deplorable that poets who are gifted, sincere and hard-working should be ignored or disparaged merely because their work is not always easy to grasp; but it will, I think, be a long time before one can hope for a disappearance of that traditional attitude which finds expression in the satirical second paragraph of Mr. Richards' letter: 'If we admit that people, however they may respect contemporary poets, do not quote them, then what Mr. Reed means by poetry and what it means to the homme moyen esthétique are two entirely different and distinct things'. Between the protasis and the apodosis of this statement there is no obvious connection; but I sense from the tone what Mr. Richards believes: that modern poetry—probably all of it—is obscure, impenetrable, esoteric, and unlovely. I do not agree with him: we can merely state our tastes. But if by the homme moyen esthétique he means the average man who takes an interest in art—the man who, for example, takes the trouble to go to W.E.A. classes, or to read regularly and seriously by himself—then I know that he very much underestimates that man's tolerance, patience and curiosity. Mr. Richards lacks these qualities, and is wrong to put himself beside the homme moyen esthétique. He is the homme moyen philistin; and he is proud of it.

It is more profitable to discuss Mr. Richards' first paragraph. He is right in assuming that Rupert Brooke achieved far greater popularity than any poet of today. This was not, however, due to any particular poetic merit; Brooke's talents were, in fact, of the slightest. He achieved his unparalleled popularity, I believe, simply because he contrived at an appropriate moment to falsify the nature of war in a way that the public found palatable. He himself is not to be blamed for this; had he lived, he might have regretted his five war-sonnets (and had he lived, he would probably never have been so famous). For they show a defect of imagination which in a poet is serious to the point of catastrophe. And Brooke saw very little of the war itself, and nothing at all of the long-term horror which might have filled the gap his imagination failed to fill. He wrote in enthusiastic ignorance; death in battle appeared lovely; there was no suggestion that war might be a tragedy. This was all highly consolatory to those whose task it was to keep the home fires burning. He was a poet for the thoughtless; and there is no fundamental difference between his war-poetry and the present-day song beginning 'There'll always be an England'.

The poets who saw what war was really like, who saw it for a long time, and who unflinchingly described it—Owen and Sassoon, for example—did not fare so well, either during or after the war. It is alongside them that I would put the best war-poets of today: such poets as Lewis and Keyes. And though they may not be widely quoted—whatever that is worth (and it may be remembered that Housman is easier to quote than Milton)—their success with the general public is a hopeful sign that people are able to 'take' a little more in the way of honesty than they used to be. It is worth while adding that Lewis's Raiders' Dawn sold well, even before Lewis's death. But neither of them has had the freakish success of Rupert Brooke or Julian Grenfell; nor would they have hoped for it.

Mr. Grigson is right in assuming that I have not read Mr. Auden's new book, which has not yet been published over here. No one could look forward to it with more eagerness than I do: I hope it is as good as Mr. Grigson says; if it is, it will survive Mr. Grigson's praise.

BletchleyHenry Reed

|

1526. Blunden, Edmund. "Poets and Poetry." Bookman, n.s., 1, no. 4 (July 1946): 14-15.

Edmund Blunden says Reed's Lessons of the War poems 'have captured something of the time-spirit and ambiguity of the recent war in a style of wit and deep feeling united.'

|

LibraryThing (remember LibraryThing? We had a visit from Tim, back in the day) went live last week with a neat new app: LibraryThing Local. I don't usually Oo and Ah over stuff that's all Web 2.0ey, but this is pretty neat.

It's basically a mapping system which allows LibraryThing members to add "venues": libraries, bookstores, festivals, and other book-related locations and events. For instance, here's all the recently-added venues within five miles of The Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. (zipcode 20540). Thingology has a post with a bunch of other examples.

Users can bookmark their favorite spots, and libraries and bookstores can even officially sponsor the entries for their venues, if they didn't add themselves.

Here's the LibraryThing blog announcement of the new service, and an update after the first 9,000 venues were added.

|

1525. "Reed, Henry," Publishers Weekly, 152, no. 15 (11 October 1947), 1945.

A note on the publication of the American edition of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

[The following is a response to two articles written by Henry Reed, " Poetry in War Time: I—The Older Poets," and " Poetry in War Time: II—The Younger Poets," which appeared in The Listener in January, 1945. This letter to the editor, by George Richards, is mentioned in Spirit Above Wars, by Dr. Amitava Banerjee.]

The Listener, 1 February, 1945. Vol. XXXIII. No. 838 (p. 129) [.pdf]

Poetry in War Time

Mr. Grigson challenges Mr. Henry Reed's ideas about war-time poetry because he does not find his own pet Auden anointed pope among contemporary poets by Mr. Reed in his first article. With your permission I would like to challenge 'Poetry in War Time' in a much more fundamental way. In the last war we had young poets writing, notably Rupert Brooke, quotations from whose poems were on everybody's lips. To have gained fame then as a poet was to be a national symbol. Now I would like to ask, in a purely scientific-objective spirit, whether there is a single four-line sequence (leave alone an entire short poem) to the credit of any of these poets mentioned by Mr. Reed which has in the same way struck the popular imagination and become common property, as did, say, several of the poems of Rupert Brooke on publication? In other words, can either Mr. Reed or Mr. Grigson quote anything written by any of the poets here complimented on their gifts which has won renown outside the literary periodicals?

I am neither so foolish as to lay it down absolutely that public (mis)quotation is a test of poetic merit nor sufficiently arrogant to assert, in the light of the results of such a test, that Mr. Reed's poets have no merit and that therefore the titles of his articles should have been 'Rubbish in War Time'. But what I do assert unhesitatingly is that if we admit that people, however they may respect contemporary poets, do not quote them, then what Mr. Reed means by poetry and what it means to the homine moyen esthétique [aesthetic of the common man] are two entirely different and distinct things. Counting myself among the latter, the more present-day poetry and poetic criticism I read the more I realise that I only deluded myself in ever thinking I understood or appreciated poetry. What I got was merely the potent but cheap thrill at the sound of mysterious but unobscure words.

PooleGeorge Richards

|

1524. Reed, Henry. Letters to Graham Greene, 1947-1948. Graham Greene Papers,

1807-1999. Boston College, John J. Burns Library, Archives and Manuscripts Department, MS.1995.003. Chestnut Hill, MA.

Letters from Reed to Graham Greene, including one from December, 1947 Reed included in an inscribed copy of A Map of Verona (1947).

|

Two fortuitous happenings this weekend. Firstly: more than a week ago—before I traipsed down to Duke University and back, even—I photocopied two articles from 1961 at the university library. One was Reed's book review of Emma Hardy's Some Recollections from The Listener, and the other was a review of Three Plays, by Ugo Betti, from Prairie Schooner. In my haste to read the Listener article, I managed to leave the Schooner review on the copier output tray.

Going back to the library this evening, I re-pulled the 1961 Prairie Schooner volume from the shelf, and when I arrived at the photocopier what should I find? My copies from the previous week, neatly arranged on the adjacent work table. Buddha bless Duplication Services!

The second happening took place at the local Barnes & Noble, where I was attempting to take account of all the articles, reviews, and letters I had dug up down at Duke. B&N's wireless service conked out after an hour or so, however, so after I had finished licking the inside of my coffee cup, I went down to peruse the Poetry section on my way out. A paperback copy of The Letters of Robert Lowell (bn.com) caught my eye, and I immediately turned to the index, under "R". There was one entry for Reed, in a letter to Elizabeth Bishop, who had left Brazil to take a job teaching at the University of Washington, Seattle:

February 25, 1966

Dearest Elizabeth:

Wonderful your letters are pouring out again. I had terrible pictures of you despondent and lost in the new toil of teaching—lonely, cold at sea. Lizzie taught last term at Barnard for the first time in her life. Her first comment was 'the students aren't very good, but I am...[.]'

Your book is another species from almost everything else. I think even the reviewers now see that there's no one, except Marianne Moore at all comparable to you. I guess I struck Roethke under a bit more favorable circumstance. I mean last year when I came to Seattle, I was to give the Roethke Memorial reading and had worked myself into the proper state of awe...[.]

Do tell Reed to come and see us. He must have saved your heart in exile. What a difference an intelligent voice makes. Our Guadeloupe beach was restoring, but one felt stupider than the stupidest tourist—and was!

All my love,

Cal

Lowell signed all his letters to friends as "Cal". Bishop must have mentioned that Reed was also teaching at the university in a preceding letter.

I was pleased to discover that Lowell's Letters are arranged the way a collection of correspondence should be; the credit going to the editor, Saskia Hamilton. There is a substantial appendix of notes at the end of the volume, detailing all the obscure and personal references in the letters; a list of all the manuscript collections where the letters were collected from; and a list of all the addresses Lowell lived at and wrote from. At the time, in 1966, Lowell was living at West 67th Street, New York.

I have no idea if Bishop ever passed along Lowell's invitation for a visit.

|

1523. Reed, Henry. "Simenon's Saga." Review of Pedigree by Georges Simenon, translated by Robert Baldick. Sunday Telegraph (London), 12 August 1962, 7.

Reed calls Pedigree a work for the "very serious Simenon student only," and disagrees with the translator's choice to put the novel into the past tense.

|

[The following is a letter to the editor, in response to Henry Reed's article, " Poetry in War Time: The Older Poets," which appeared in The Listener on January 18, 1945. Reed's two-part series on the poets working during the period 1939-1944 led to a lively exchange of letters debating the merits of modern poetry, with particular regard to a comparison of the poets of the Second World War and those of the first, Great War. Over the next week, we will reproduce the exchange of letters, here. We begin with the poet and editor, Geoffrey Grigson.]

The Listener, 25 January, 1945. Vol. XXXIII, No. 837. (p. 104) [.pdf]

Poetry in War Time

Writing of 'Poetry in War Time' Mr. Henry Reed says, and says only of Mr. W.H. Auden, that 'Two volumes by Auden have appeared, but they consist mainly of pre-war work'.

In America, in 1944, Mr. Auden's book For the Time Being was published. I daresay few copies have arrived over here; but when Mr. Reed does get hold of one, and does digest Mr. Auden's long commentary on 'The Tempest' which is called 'The Sea and the Mirror', he may overhaul his opinion about who 'has made the greatest contribution to poetry in the last five years'. In my judgment 'The Sea and the Mirror' secures Mr. Auden in the place many of us know him to occupy—as the most inquisitive, moving, serious, the best and most diversely equipped poet now writing in English.

KeynshamGeoffrey Grigson

|

1522. Reed, Henry. "Hardy's Secret Self-Portrait." Review of The Life of Thomas Hardy, by Florence Emily Hardy. Sunday Telegraph (London), 25 March 1962, 6.

Reed says this disguised autobiography is a "ramshackle work," but is still "packed with a miscellany of information not available elsewhere, and readers who care for Hardy will find it everywhere endearing, engaging, and full of his characteristic humour."

|

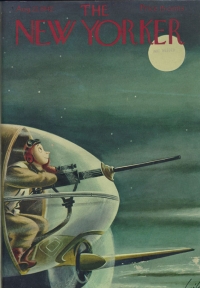

Here's a New Yorker cover from World War II which bears comparison with " Naming of Parts." It depicts a daydreaming nose gunner in (what looks like) a stylized B-24.

From American Studies at the University of Virginia's Covering the War section of Urban and Urbane: The New Yorker Magazine in the 1930s:

[E]ven preoccupied with the thoughts of death, honor, and heroism that doubtless passed through the heads of millions of American soldiers on the eve of battle, the young man cannot resist the natural beauty of the full moon on a clear night. The image also plays with the sharp contrast between the plane, the latest in American technology, and the vast emptiness of the sky. It makes a subtle yet present commentary on the just how much technology has still yet to do.

The depiction also stands in stark contrast to that other famous poem of the war, Jarrell's " The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner." The illustration appears on the cover of August 22nd, 1942 issue of The New Yorker ( full size), and is by the Russian-American artist, Constantin Alajalov.

A print of Alajalov's cover is available from The Cartoon Bank. (Via Kottke.)

|

1521. Reed, Henry. "Leading a Dance." Review of Fokine: Memoirs of a Ballet Master, translated by Vitale Fokine. Sunday Telegraph (London), 26 November 1961, 6.

Reed finds Fokine's memoirs "very absorbing and intelligent."

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|