|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Reviews"

|

|

|

27.4.2024

|

Re-entering the time machine that is the British Newspaper Archive, I have turned up another couple of early book reviews by Henry Reed, in his hometown Birmingham Post during 1944 and 1945. Here, Reed reviews the posthumously published "last" poems by Laurence Binyon ( December 27, 1944, p. 2), including the titular " The Burning of the Leaves," written during the London Blitz:

"They will come again, the leaf and the flower, to arise

From squalor of rottenness into the old splendour.

And magical scents to a wondering memory bring;

The same glory, to shine upon different eyes.

Earth cares for her own ruins, naught for ours.

Nothing is certain, only the certain spring." Interestingly here, Reed refers to the ongoing war as "a second Great War": a war he was still enduring in 1944, working in the Japanese section of Bletchley Park.

Binyon's Last Poems

The Burning of the Leaves. By

Laurence Binyon. (Macmillan. 2s.)

By Henry Reed

Some enterprising readers will already know the five poems which give this superb little book its title; they appeared in "Horizon" in October, 1942, under the title of "The Ruins." Some will also know the exquisite "Winter Sunrise," which appeared in the "Observer" shortly after Binyon's death. This book includes variant readings for "The Burning of the the Leaves," and a draft, including some fragmentary passages, of the unfinished next section of "Winter Sunrise." Binyon's habit in composing, we are told in a foreword, "was to start by jotting down isolated lines or parts of a line and to cover pages with these, repeating, correcting, expanding and revising, and so gradually shaping the whole poem." It is always interesting to see how different poets work; when the poet has Binyon's sincerity and feeling and power over words, this becomes a most moving experience.

"The Burning of the Leaves" is among the most beautiful of modern poems. It is a tragic poem, for the war—a second Great War—provides its background; but it has classical control and mastery, a magical use of its imagery, and a calm finality which, among contemporary poets, are to be found elsewhere only in Mr. T. S. Eliot's latest poems. There are other poems in the book which few readers can fail to love: "The Cherry Trees" and "The Orchard" have a perfect clarity, delicacy and lightness which show something of what Binyon learned from the Orient.

|

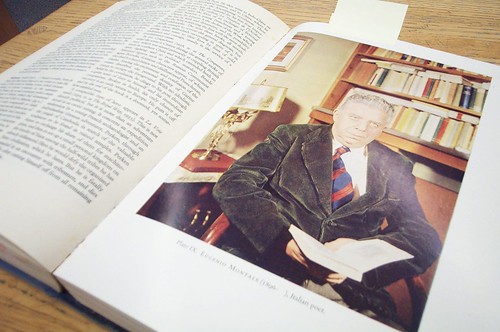

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

Defying the notion that we have somehow already found everything written by Henry Reed to be found, up pops another book review in the June 3, 1944 issue of Time & Tide. (Reed reviewed Eliot's Four Quartets in December, that year, and I'm beginning to think he may have been something of a regular contributor.)

In this article, Reed critiques new poetry by three of his peers (or soon-to-be peers, since Reed's own volume of poetry, A Map of Verona, would not be published until 1946): John Heath-Stubbs, Julian Symons, and Terence Tiller.

POETRY

The Inward Animal: Terence Tiller. Hogarth. 3 s. 6 d.

Beauty and the Beast: John Heath-Stubbs. Routledge. 5 s.

The Second Man: Julian Symons. Routledge. 5 s.

in one of his poems Mr Symons says of himself:

"My poems are paper games, kicking a football,

Negative, disgraceful." This, though rather severe, is true. The word, "disgraceful" suggests something more vividly objectionable than anything Mr Symons has yet achieved, but "negative" and "paper games" are fair enough descriptions. "Paper games" is particularly apt; for here we have a characteristic contemporary volume of poems which very quietly, indeed almost unobtrusively, shuffles round and round those great concepts which Mr Auden has, by constant repetition of their names, so curiously reduced in seriousness: life, death, evil, corruption, sin, error, love, time and what not. The disposition of these little objects according to personal or fashionable taste is indeed a paper game, and a game available to anyone who cares to play it. Here is an example:

Our tears drop, the wet pearls are

Transformed into a voice

Crying: "O pity human

Nature condemned, to error,

And all those good who dare not

Descend like furious birds."

Weak as a baby walking

Conscience now moves and tells them

All inappropriate action

Leads on to wrong and death. Mr Heath-Stubbs and Mr Tiller are to be taken much more seriously. Mr Heath-Stubbs is at his best when he avoids traditional stanza-forms, which make him sometimes seem insincere and artificial, as in the various "songs" in his new volume; and even in the sequence of sonnets called The Heart's Forest, which deal with an important personal experience, the sonnet form is often used too lightly and casually. Nevertheless this sequence has some unusual and successful things in it: among them a sonnet beginning "Three walked through the meadows", and another on the theme of Echo and Narcissus. It is in Mr Heath-Stubbs's longer poems, usually written in a loose blank-verse, that one finds his best work: poems such as "Leporello", "Moscatos in the Galleys" and "Edward the Confessor", and a "Heroic Epistle" supposedly written from Congreve to Anne Bracegirdle. He is particularly good at identifying himself with a figure of the past, as Browning did; indeed he continues the Browning-Ezra Pound tradition. Here, presumably, is Liszt speaking:

'And the flutes ice-blue, and the harps

Like melting frost, and the trumpet marching, marching

Like fire above them, like fire through the frozen pine-trees

And the dancers came, swirling, swirling past me—

Plume and swansdown waving, while plume over the gold hair

Arms held gallantly, and silk talking—and an eye caught

In the candle-shadow, and the curve of a mouth

Going home to my heart (the folly of it!) going home to my heart!: Mr Tiller has forced on to his new volume of poems an order which appears to be rather false. The body of the book is a collection of lyrics, mainly meditations on emotions woken by a prolonged sojourn in Egypt. These he has written with all the customary fastidiousness, independence and conscientiousness. He is a poet who neither goes in for, nor comes out with, memorable lines or phrases. It is the atmosphere in his poems that one remembers—in a brilliantly composed poem such as Egyptian Dancer, for example, or in the poems called Desert:

Still where the viper swims in sand, the pearly

Scorpion stiffens, and the fast-mouthed surly

Lizards are—here, looking towards the waste,

We know more bare an importance than dust

Or the dry ant-clean specters that are born

Of it, venom of the scale and horn. He has flanked his collection of lyrics with two long poems, Eclogue for a Dying House, and The Birth of Christ. The former of these is intended to present the death of the old pre-war personality of the poet, the latter to present "slow mutual absorption ending in the birth of Something at once myself and a new self and Egypt". These poems, the most ambitious in the book, are the least successful—perhaps because they recall other poets very strongly, and Mr Tiller is good only when he is original. The Eclogue is a weary and powerless poem; its title and mode inevitably recall Mr MacNeice, but the poem is without Mr MacNeice's accomplished patina. The Birth of Christ employs a symbol too great for what Mr Tiller describes in his comment on the poem; and Rilke has been too unscrupulously impressed into helping in the writing of it.

henry reed

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

For the centennial of his birth on April 15, here is a book review of Emyr Humphreys' first novel, The Little Kingdom (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1946). Written by Henry Reed, it appeared in The Listener's "New Novels" column for January 6, 1947. Reed expresses a familiarity with Humphreys' poetry, stating that the author certainly "knows how to write, and you feel as you read him that he knows that apprehension and diction must, in prose and verse alike, be clasped as earnestly as two hands in prayer."

It appears the two corresponded for a while, in 1947-1949 (Emyr Humphreys Papers, National Library of Wales), and Reed discussed Humphreys' next book, The Voice of a Stranger, for a B.B.C. radio talk in 1949.

Reed also reviews here an English translation of C.F. Ramuz' The Triumph of Death, and The Becker Wives, stories by Mary Lavin.

New Novels

The Little Kingdom. By Emyr Humphreys. Eyre and Spottiswoode. 9s.

The Triumph of Death. By C. F. Ramuz. Routledge. 8s. 6d.

The Becker Wives. By Mary Lavin. Michael Joseph. 9s. 6d.

WHAT is the most positive quality we have to recognise in a new novelist in order to feel that his work contains promise as well as immediate success or in spite of immediate failure? It is, I suspect, his style: whether it is already individual or assured, or whether it merely indicates a preoccupation with the act of writing.

A war plays hell with prose. There is always the influx of new technical terms and clichés, there is always the politicians' jargon; these are small in themselves, perhaps, but if they pervade our speech, as they are likely to do when our ideas are confused, they will shortly afterwards pervade our writing also. The most depressing thing that confronts a novel reviewer at the moment is the general beastliness—I have pondered this word before using it—of the various ways in which most novels are written. The mediocre novelists of thirty and forty years ago at least believed that they should try to write well. They believed, if not that a good writer must always appear en grande tenue, that the disorder in his dress must be a sweet one. They believed it mattered how a book was written. Of Mr. Emyr Humphreys, a new novelist not unknown as a poet, one can use many nice and conventional expressions: he is worth watching, he is a novelist of whom we shall hear more, he has something to say and he knows how to say it. I think this last thing is the most interesting thing about him. He knows how to write, and you feel as you read him that he knows that apprehension and diction must, in prose and verse alike, be clasped as earnestly as two hands in prayer. I think that the strength of a young writer's religious, political and psychological perceptions are usually less important than his sense of style. Here is a passage from The Little Kingdom: it is, as may be guessed, a mere 'bridge-passage' in the action; but it is clearly the work of a very able writer: The little bell over the door giggled as the minister went in, and echoed the giggle as he closed the door carefully behind him. He screwed up his eyes. After the soft twilight outside, the harsh naked electric light in the barber's shop was painful to him. He said 'Good evening, everybody', but all he could make out at first was the white blur of the barber bending over someone indistinct in the chair. Otherwise the shop was empty; this was the last customer for the night. The barber was too tired to talk to the man, who slumped helpless in the chair. He nodded.

'Evening, minister'.

The man in the chair stirred with curiosity, but the barber held him firm, the fingers of his left hand spread over his ruffled hair like a vice.

'Go through'.

The barber pointed to the swing door with his gleaming razor, which flashed as it caught the light.

'You'll be coming up later, Dan?'

The smiling, perfect male, advertising hair cream, swung back and fore, smile out, smile in. The last sentence will at once indicate that the 'middle' Joyce has contributed something to the formation of Mr. Humphreys' style. There are few better models for a serious young writer, and an ability to learn something from the first half of Ulysses will probably imply a kindred sensitiveness to the coalescence of sight, sound and thought in the human consciousness. The feelings which attend on being alive do not escape Mr. Humphreys, any more than they escaped Joyce.

The action of The Little Kingdom concerns the last months in the life of a dominating and imperious young Welsh nationalist who, to further his ambitions, murders a wealthy uncle, and later sets fire to an English-built aerodrome. He is shot and killed by a night watchman. I take it that one of the main ideas behind the book is the common running aside of an idealistic political movement, first into 'irresponsible' acts, and then into Fuehrerprinzip. This is a respectable theme, though not a very distinctive or profound one; but it has the advantage common to all well-tried themes that it shifts the reader's interest to the writer's talents as a particular interpreter and executant. One is curious to see how he will use his gifts. And to have emphasised Mr. Humphreys' ability to write is not to diminish his other powers. There is a touching reality about his characters—almost all of whom are muddled and pathetic. I believe that the hero-villain Owen, who is neither muddled nor pathetic, is slightly under-emphasised; though the author's avoidance of an opposite effect is doubtless intentional; Owen's first appearance is admirable. The major scenes of the book are ably got through; though for some reason it is the semi-marginal scenes that one remembers best—the opening chapter describing a morning tour made by Owen's uncle Richard, or the waiting scene on the night of the fire. It is a most remarkable intuition that makes the author delay our first and only glimpse of Richard's beloved daughter, Nest, till the moment after her death: a most curious and effective piece of understatement, for Nest is the figure on whom the subsequent action turns.

Mr. Humphreys holds our attention by the way he gets from one point of his story to the next, by certain felicitous interior echoes, by his movements from one contributory stream of activity to another. I think that a greater tragedy is needed for a writer to be able successfully to use a village lunatic—a Mayor of Casterbridge, for example—but Mr. Humphreys obviously conceives of an art serious enough to include such a dangerous piece of machinery.

It is curious that the Swiss novelist C. F. Ramuz should be so little known in this country; he is obviously a very remarkable and original writer, and one is inclined to believe the extensive claims made for him by M. Denis de Rougemont in his admirable introduction to The Triumph of Death. This is a translation, by Allan Ross MacDougall and Alex Comfort, of a book called Présence de la Mort, a better and more accurate title which it is strange to find rejected. It is a fable about the end of life on earth: disaster comes as the earth steadily and rapidly approaches the sun. The scene is set mainly on a lakeside in the Vaud country of Switzerland. It is perhaps with some misgiving that one embarks on reading such a story. It is written fancifully, and at first promises to be little more than im over-long prose-poem. I remembered, and expected to prefer, H. G. Wells's story ' The Star'. But Ramuz' book surprises and excites by its peculiar mounting intensity; one succumbs, and consents to the author's apparently arbitrary ordering of his material. Many of his scenes have great beauty; and he keeps one agog to know the end, which turns out to be both tender and wonderful. His scenes of anarchy, demoralisation and criminality are very moving, and they are never indulged in for the private delight of their author. There are many moments when the book shows signs of having offered to its translators some of the difficulties that works like Rimbaud's Les Illuminations offer; but on the whole the book comes over vividly and well. It is doubtless a point of preciosity in the original that present and past tenses are pointlessly mingled; but English seems particularly odd when such a mannerism is grafted on to it. It is to be hoped that Mr. Macdougall and Mr. Comfort will soon address themselves to the task of translating the sequel, Joie dans le Ciel. These books, incidentally, are not allegories about our recent disasters; the date of Présence de la Mort is 1925.

Miss Mary Lavin is a most prolific and varied writer. She is, so far, at her best in comedy. Her serious writing is often commonplace, and it is noticeable that when the first story in her new book, after an excellent beginning, takes a turn into. the pathological, it is a turn for the worse. But there are few writers now writing in English capable of more sustained comic scenes—scenes where the comedy depends not on conversation so much as on large-scale conception of a theme. The high spot in Miss Lavin's prodigiously long novel, The House in Clewe Street, was the brilliant scene where two funeral corteges attempted to race each other to the cemetery; there is a similar vis comica pervading two stories in the new book: 'Magenta' and 'The Joy-ride', both about surreptitious outings made by servants. Intermittently throughout the book there is to be found Miss Lavin's particular talent for startlingly transfixing a scene: the moment in 'The Becker Wives' where Flora makes the stolidly respectable family involuntarily pose for an imaginary photograph, for example, or the vision of the upstart kitchen-vestal Magenta crossing the park in her borrowed finery. It is with regret that one adds that Miss Lavin's grammar is so bad that from time to time one gazes at it in surprise.

HENRY REED

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

Here we find a letter from Evelyn Waugh to the novelist Nancy Mitford, written in 1946, regarding a review in the New Statesman and Nation by Henry Reed, of Mitford's novel, The Pursuit of Love.

Waugh is "irritated" by Reed's review, and by newspapers and journals and news, in general. Waugh doesn't know who Reed is, and even seems to think the byline on the review is a pseudonym (this despite Reed having reviewed Brideshead Revisited just the year previous). Waugh does somehow infer Reed's homosexuality on the basis of his review, but mistakes him for a lesbian.

This from the The Letters of Evelyn Waugh, edited by Mark Amory (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980), pp. 222-223: Piers Court. To NANCY MITFORD

4 February 1946

Dearest Nancy,

Since sending you a post-card today I purchased the New Statesman. I thought 'Reeds'1 review of your book egregiously silly both in praise & blame. I love all the Mitford childhood, as you know, but to single out the buffoon father while totally ignoring the unique children's underground movement is brutish. He calls your one false character 'a brilliant sketch'2. You know better than I how wrong he is about Fabrice. The review irritated me greatly. I wonder who it is who writes it. Plainly a homosexual; perhaps a Lesbian?

I looked at other pages of the paper & was astounded that you take it in. I read Eddie [Sackville-West] describing the use of the word 'brothel' on the wireless as 'a refreshing experience which spoke eloquently of the intelligence, sanity and good feeling of ordinary people'. I read 'Nothing can stop big Powers bullying their small neighbours if they wish to do so'. Last time I had the paper in the house it was boiling to attack Germany & Italy for no other reason. I read the wild beast saying that Mr Sutherland's painting 'rivals butterflies wings in delicacy.'3

The only thing that made any sense in the paper was a grovelling apology to a soldier they had insulted, but that had been dictated, presumably, by some intelligent solicitor.

How can you read it? It explains all that modern trash that encumbers your shop.Evelyn

1 Henry Reed (1914- ). Poet and BBC producer.

2 Talbot, the middle-class communist in The Pursuit of Love.

3 Raymond Mortimer was reviewing The Approach to Painting by Thomas Bodkin.

Here is the irritating review, from the New Statesman for February 2, 1946. Reed invokes several lessons from Joyce, including the best description of synecdoche ever written: "When a part so ptee does duty for the holos we soon grow to use of an allforabit."

NEW NOVELS

The Pursuit of Love. By Nancy Mitford, Hamish Hamilton. 8s. 6d.

Of Many Men. By James Aldridge. Michael Joseph. 8s. 6d.

The Crater's Edge. By Stephen Bagnall. Hamish Hamilton. 6s.

Everybody will remember that encouraging moment on page 108 of Finnigans Wake when, into the sleeping mind of H. C. Earwicker, as he toils over the difficulties of Anna's elusive letter, there flow these calming words: "Now, patience; and remember patience is the great thing, and above all things else we must avoid anything like being or becoming out of patience. A good plan used by worried business folk ... is to think of all the sinking fund of patience possessed in their conjoint names by both brothers Bruce ..." They are words I have often used to prop, in these bad days, my mind, as in my turn I have toiled through the pages of recent fiction. Patience is needed with all of the books listed above, even with Miss Mitford's The Pursuit of Love, which is rewardingly funny in many places. This is the least, and indeed the most, one can say of it. It begins extremely well with a picture of the children of an aristocratic family called Ratlett. Its early pages introduce, in Uncle Matthew and Captain Warbeck, two of the best comic figures in any modern novel, I cannot recall a funnier picture of the violent foreigner-hating patriarch than Uncle Matthew; his early morning foibles are beautifully recorded:He raged around the house, clanking cups of tea, shouting at his dogs, roaring at the housemaids, cracking the stock whips which he had brought back from Canada on the lawn with a noise greater than gun-fire, and all to the accompaniment of Galli Curci on his gramophone, an abnormally loud one with an enormous horn, through which would be shrieked "Una voce poco fa"—"The Mad-Song" from Lucia—"Lo, here the gen-tel lar-ha-hark"—and so on; played at top speed, thus rendering them even higher and more screeching than they ought to be.

... the spell was broken when he went all the way to Liverpool to hear. Galli Curci in person. The disillusionment caused by her appearance was so great that the records remained ever after silent, and were replaced by the deepest bass voices that money could buy. But, alas, though Uncle Matthew dodges in and out of the whole book, the later pages are given over to the affairs of one of his daughters; Linda. It is to her that title refers. The less successful episodes in her pursuit—her marriages with the banker Kroesig, and with Talbot, the middle-class Communist (a brilliant sketch)—are convincing enough; but at a moment of despair she is picked up by a French duke and installed as his mistress, and thenceforward the novel has the sentimental staginess of the late W. J. Locke. It has a certain characteristic contemporary wistfulness in its English admiration for the high-handed way in which upper-class French Catholics are presumed to fornicate, and one is interested to learn that the French are surprised if a woman does not express honte after a night with a lover. But it has also a dreadfully soft centre, and one is not surprised that Fabrice should eventually discover that what he feels for his enslaved mistress is the real right thing. They have both become unbelievable by the time Miss Mitford finally polishes them off; and in the later pages the irruptions of Uncle Matthew preparing to hold his house against the German invasion are a great relief:"I reckon," Uncle Matthew would say proudly, "that we shall be able to stop them for two hours—possibly three—before we are all killed. Not bad for such a little place." Of Many Men and The Crater's Edge each exemplify an extreme of mannerism which we may expect in war-fiction for many years to come. Of Many Men is the extremely hard-boiled type of war-novel, The Crater's Edge the extremely soft-boiled type. This is nowhere better illustrated than in the prose style of the two writers; in offering for the reader's judgment a little example of each, I am reminded of yet another of Joyce's persuasive remarks: "When a part so ptee does duty for the holos we soon grow to use of an allforabit." Here, for instance, is a characteristic passage from Mr. Aldridge:Wolfe entered Damascus with the French. The day after they arrived the Germans invaded Russia. Wolfe got the first Nairn bus that went to Baghdad and then he flew over the dead mountains to Teheran.

The Russians in Teheran said they were sorry that Wolfe had been in Finland, very sorry; but if he waited maybe he would get a visa. He waited a long time and the Red Army was still retreating to the Dnieper when he left Teheran. He could not get a visa.

The Germans were also in the Western Desert now. They had pushed the British back in to Egypt and had encircled and isolated the Australians at Tobruk. Wolfe went into Tobruk on one of the relief boats. And here we have Mr. Bagnall:If a girl loves someone at the age of sixteen for whom she has protested the madness of her love as a child of eight, even then he cannot be sure of her constancy, because, since nothing came of that protestation, nothing has flowered, and therefore nothing has had an opportunity to either flourish or die. Rather it has been in a state of perennial bud. So at first he made a noble decision of renunciation. Or perhaps it was not so much a decision he made as an attitude that he struck. Because he knew all the time he would not remain faithful to it. Yet he held it long enough to crystallise, or perhaps embalm, it in a sonnet of great-hearted finality and generous resolve. Generous himself at this point, Mr. Bagnall spares us the sonnet; but he spares us little else. His theme is one of those old, well-tried ones, which were never any good even when new: the theme of the dying man reliving the past. Not even vivid interludes can remove the distrust one has for a story whose end is also its beginning; and Mr. Bagnall's story has no vivid interludes. It is merely a series of lush reminiscences about the hero's four loves: his love for a ballet dancer (platonic), for a schooldays' friend ("without lust"), for a girl called Celia (with), and youthful Elizabeth (the real right thing once more) With its juicy, self-admiring prose, its purple passages, its recklessly misrelated participles and its lengthy commonplaces about the major problems of life, it is not an easy book to read.

The point of Mr. Aldridge's book lies quotation which prefaces it: "War is the shape of many men, those in the sun and those the shade; many hands clear the shade, but in truth they have only succeeded when the last shadow is gone." The book begins with its hero, emerging from the Civil War in Spain; during the next few years, in an unspecified capacity, he tours the second world war in Finland, Norway, Syria, Africa, Malaya, the Pacific, Italy and Germany; the facility with which he gets about will be seen in the passage I have quoted. After VE Day he announces his intention of returning to Spain, and the point of the book is made clear. Presumably if Mr. Aldridge had waited a month or two longer, we could have accompanied his hero to the bombing of Hiroshima (doubtless inside the actual aircraft) and to the meetings of Hirohito and MacArthur. The pity is that even when we have had the overwhelming course to accept Mr. Aldridge's style as a means of communication, he appears to have nothing to communicate beyond his central statement; the scenes we visit as we fly from one battle-front to another are stupefyingly machine-made. And though none will doubt the the truth of his epigraph, and few will doubt its application to Spain, it is a pretty bald gag to write a book about.Henry Reed

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

Henry Reed was, for a short time in the 1930s and 40s, the consummate Hardy scholar. Reed wrote his master's thesis at the University of Birmingham on " The Early Life and Works of Thomas Hardy, 1840-1878." He visited Florence Emily Hardy in 1936 as part of his research, and sat in Hardy's study at Max Gate transcribing letters.

Reed's ambition was to write the life of Thomas Hardy. He was thwarted by his own perfectionism, and — according to this 1962 review from the Sunday Telegraph of the republication in one volume of Florence Hardy's Life of Thomas Hardy, 1840-1928 — by Thomas Hardy, himself. The official biography which was published in 1928 and 1930 was nothing less than Hardy's own autobiography.

Reed's scholarly adventures eventually provided the fodder for his sequence of Hilda Tablet radio plays featuring the late "poet's novelist," Richard Shewin, as a stand-in for Hardy.

Reed's frustration with trying to write his own life of Hardy is scarcely disguised in his book review, but it can also be heard the most perfect parody of Hardy's poetry, " Stoutheart on the Southern Railway," written by Reed sometime in the 1950s:

What are you doing, oh high-souled lad,

Writing a book about me?

And peering so closely at good and bad,

That one thing you do not see:

A shadow which falls on your writing-pad;

It is not of a sort to make men glad.

It were better should such unbe. When Reed finally abandoned his Hardy project he donated his notes to professor Michael Millgate, whose first book on Hardy, Thomas Hardy: His Career as a Novelist, was published in 1972, with a full-blown Thomas Hardy: A Biography following in 1982.

Hardy's Secret

Self-Portrait

By HENRY REED

The Life of Thomas Hardy BY FLORENCE EMILY HARDY. Macmillan, 30s.

Many artists have led two lives, and out of consideration for their biographers they have usually contrived to lead them both at the same time. Thomas Hardy also had two lives, but they were inconveniently placed end to end.

There is a great division in his life round about 1897 when he ceased to be a novelist and returned to poetry. Biography of him will always be, from the point of view of shape, bedevilled by this fact.

There is plenty of incident, movement and emotional adventure in the first 57 years of his life. In the last 30 years that remained to him—from his own point of view his most valuable creative years—biographically dramatic landmarks are few indeed.

Official Life

The present volume suffers unavoidably from this tailing away of interest. It is the "official" life, originally published in two parts, the first in 1928 within a few months of Hardy's death, the second in 1930.

The work is still attributed on its title page to the second Mrs. Hardy, and we are left to wonder how its publishers have never got wind of the real facts of its composition, which were divulged as long ago as 1954 in Richard L. Purdy's monumental bibliographical study. The Life of Thomas Hardy is, in fact, save for its last four chapters, Hardy's own autobiography, and should be announced as such.

It is, by any standards, a ramshackle work, and its information is in may places demonstrably inaccurate even where there seems no point in disguise. But the book is packed with a miscellany of information not available elsewhere, and readers who care for Hardy will find it everywhere endearing, engaging, and full of his characteristic humour:

"There are two sorts of church people; those who go and those who don't go: there is only one sort of chapel-people; those who go."

There is, above all, the sense of being "with" Hardy himself: every page is invested with his own idiosyncrasies of vision and style.

Dorset Childhood

The early chapters are particularly impressive. He recreates his childhood and youth in Dorset and his days in London with fair objectivity. There is much room for correction of fact, but in mood and atmosphere his own account will scarcely be bettered.

Part of its charm comes, I think, from Hardy's genuine and characteristic modesty of manner. He was well on into his seventies when he embarked on the work, yet he never indulges in the reminiscent pride we so often have to wince at in writers' memoirs.

And there is no trace of that excessive self-esteem which sometimes indicates an unconscious sense of failure and is so painful in (to come no nearer to home) a writer like Bernard Shaw.

All the same, there is much that is defensive in these pages, and this provides strange matter for study. A good deal of care seems to have been taken to make things opaque when Hardy wished them to be.

Blank mendacity he rarely has recourse to: on the whole he probably tells fewer lies than most people. But he is at pains to mislead us about things that had affronted him in the circumstances of his own life or worried him in his relations with the highly class-conscious society of his time.

It is in his art that find the rectification of these evasions and deceptions. His art might often be bad art, its badness the more conspicuous for lying cheek by jowl with his incomparable best. But it was faithful to his own experience, and the recurrent themes of his fiction were the basic themes of his own life.

The contrast of humble birth and lofty aspiration, the struggle for education and learning, the uncertainty of passion, the dissatisfaction with marriage as solution to the problem of sex, the commonness of external adversity and of simple bad luck—all these went into his novels and his poems.

There is little or nothing of them, however, in the official life; and we are at times as conscious of this little-or-nothing as we would be if there were whole blank pages in the book.

Meant as Protest

However, the thing was not meant as confession: nor was it undertaken with any marked relish; quite the contrary. It came into being largely as a protest against recurrent public mis-statements about Hardy's own experiences. It was not meant to be a source for future biographies: it was meant to be an obstacle in their way.

So far it has proved highly successful in this aim. The biographical studies of Hardy published since his death compete lamentably with each other in the inaccuracy of their employment both of the "official" material given here and of the other pieces of significant information that seeped out in more recent years.

In the circumstances this republication—in a very convenient form—of Hardy's own account of himself is, for all its defects, a timely and refreshing recall to order.

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

Today I am dredging up a review from The Listener from November 28, 1946. In the "New Novels" column, Henry Reed considers two books which are distinctly post-war: Arthur Koestler's Thieves in the Night, based on Koestler's experiences setting up a kibbutz in British-ruled Palestine; and Henry Green's Back, regarding a wounded British soldier returning from a German POW camp. Reed also has a few favorable words for Tom Hopkinson's Mist in the Tagus, "a story of two heterosexual girls in love with two non-heterosexual young men."

Reed is disappointed in both Koestler and Green (though he gives Green's prose high marks), whose preceding works were so much more enjoyable and filled with promise, but surprisingly his biggest complaint about Hopkinson's novel is that it is too brief:

New Novels

Thieves in the Night. By Arthur Koestler. Macmillan. 10s. 6d.

Back. By Henry Green. Hogarth Press. 8s. 6d.

Mist in the Tagus. By Tom Hopkinson. Hogarth Press. 7s. 6d.In almost every way, Mr. Arthur Koestler's new novel is profoundly depressing. It depresses one on his behalf because he has suffered what he describes; on behalf of the Jews he writes about because a solution to their problems seems almost unimaginable; and on behalf of the readers who normally admire his work because Thieves in the Night is a poor book. Mr. Koestler seems indeed to be not very interested in making it any better, and I felt while reading it that the contempt he appears to feel for most groups of people had somehow invaded his attitude towards novel-writing, and — less pardonably — his attitude towards his readers.

Thieves in the Night could doubtless have been a worthy successor to Darkness at Noon; one could forgive it for being less objective, since Mr. Koestler has himself been more deeply involved in what he describes. It is a story about a group of Jewish immigrants to Palestine. They arrive on a night in 1937; the book tells about their building of a settlement; it carries us through their days of achievement, setback, and hardship, up to the time of the 1939 White Paper. It ends with another small batch of immigrants arriving in Palestine in the same year. Threaded through this chronicle of events is the personal story of Joseph, a half-Jew who has joined the Zionists; the girl he loves is murdered by Arabs, and this turns the scale for him so that he throws in his lot with the terrorists. I do no think we are to assume an identity between Joseph's views and Mr. Koestler's, though I see that this has been promptly taken for granted in some quarters. What he shows us is an example of how 'those to whom evil is done do evil in return'; and he convinces us that a sober and dignified effort towards a good life has become transformed by frustration and betrayal into lawless violence. The plight of the Jews is described thus:

We are homesick for a Canaan which was never truly ours. . . . Defeated and bruised, we turn back towards the point in space from which the hunt started. It is the return from delirium to normality and its limitations. A country is the shadow which a nation throws, and for two thousand years we were a nation without a shadow. Mr. Koestler has summed up the tragedy in that unforgettable last image; and it is obvious that his subject is a great one. It is here that one's cause for depression rises: rarely can such a subject have been so dully and so mechanically treated. We are given many illuminating facts; but during scarcely more than a dozen pages does the book come alive as an original story; these are page after page of discussion, of would-be satirical portraiture which I feel any novelist anxious to do a good job would have seen to be commonplace and flat. No readers enjoy more than do English readers satire about themselves abroad; but A Passage to India, to say nothing of other books, has set a standard in this sort of writing which one cannot ignore.

And, alas, Mr. Koestler tends more and more to become a publicist. He is perhaps not to be blamed. It is an easy line, and doubtless it is justifiable. I can imagine that tolling in his ears is the death-knell of civilisation. Art seems increasingly crowded on to a narrowing littoral and facing an incoming sea. I think a critic is called upon to understand and sympathise with this point of view; he is also called upon to say that straight polemical writing is more readable than the casual dramatisation found in Thieves in the Night. It seems idle to suggest that, with his gifts, Mr. Koestler could have developed his characters to a point where they become interesting, and cease to be merely a set of wooden objects asking the reader for pity. We know that if Mr. Koestler cared to try, he could force the pity from us. We know that he could also make us laugh, but here, as in his play, 'Twilight Bar', he prefers facetiousness. The solemn importance of the subject prevents one from ignoring the book; but it is a great disappointment.

So many intelligent novelists in recent years have eschewed the use of plot and substituted what may be charitably called 'theme' that the sight of sort of plot emerging from a novel goes to a reviewer's head. The position is much the same with wines. Years of tormenting abstinence deaden one's judgment. Plots and wines return, and at first it seems in both cases that any blessed thing will do. The excitement of wanting to know what will happen next leads one to murmur preliminary words of extravagant praise. Then the plot falters, the wine doesn't turn out as well as you expect, and your words of praise have to be withdrawn. Thus with Mr. Henry Green's new novel, Back. It starts an attractive story about a man named Charles Summers returning with a peg leg from a prison camp; Rose, his former mistress, the wife of a friend, has died. By a curious contrivance Charley is introduced to her illegitimate half-sister, Nancy; he cannot believe she is not Rose herself with her hair dyed. It is part of the nightmare quality of being 'back'. I do not object to an improbable plot. But Mr. Green's plot totters; it too is peg-legged and has to have a long rest in the middle. Its end is convincing and beautiful, but by the time it comes we have slightly lost interest.

If you know Mr. Green's other novels, its curt title will suggest to you at once that he has chosen a good 'theme' for himself; there is the intensity of feeling found in Caught and Loving. The ideas that he implies in his titles are for him poetic ideas, as summer or winter might be to a poet. It is this that makes Mr. Green one of the most striking and original of modern novelists. To me he seems also one of the best. He does something new and good. I can see that his curious style may be an irritation to some readers; me it normally charms. Adaptations of highly mannered authors are always dangerous; but Mr. Green seems to find genuine kinship with the sad, wistful mood of the earlier Bloom chapters in Ulysses. His echoing poetic images, recurring and transformed like musical phrases, are to him a natural and not an artificial way of seeing and feeling; and they reproduce something real in our own sensitivity. His new novel contains ay fine passages; its comedy is excellent. If it is less of a success than its two immediate predecessors, it is nevertheless something one will keep with Mr. Green's other books and take down from time to time.

Mr. Tom Hopkinson's second novel, Mist in the Tagus, has a fault staggeringly unusual in contemporary novels: it ought to have been longer. The people and emotion he deals with demand greater space for their proper emergence than he has allotted them, so that relationships which should have been dramatised are often merely described: there is a felling that some of them have been unduly potted. It is a story of two heterosexual girls in love with two non-heterosexual young men. It occupies the week or fortnight of an English girl's holiday intrusion into a leisured small group of people who have drifted down from Europe into Portugal. The feeling of rapidly shortening time as the girls attempt to accomplish their desires is excellently achieved; so is the sense of inevitable failure which pervades their efforts. Everything in the book is well conceived and well ordered; the actual succession of events and disclosures shows a most intelligent and perceptive writer at work. But the final feeling one is left with is that one has seen it all through the wrong end of a telescope. Today this seems like being given an ounce of best butter in place of a pound of common marge. One hardly knows whether to be grateful or not; it is another aspect on the plot and wine situation referred to above.

Henry Reed

[p. 766] You can read the original New York Times review for Thieves in the Night on their website.

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

I was recently led by a database — and ultimately disappointed — to an issue of Vogue in 1948 containing reference to Reed. It was in an article on the Sitwell dynasty: Edith, Sacheverell, and Osbert Sitwell. The article, which appeared in the November 15 issue, " The Importance of Being the Sitwells," has a layout of paintings and photographs, while the text consists of pullquotes and anecdotes concerning the trio (mostly Dame Edith, let's be honest) from a myriad of sources. Reed's paragraphs (on the last page), are sourced as being from Denys Val Baker's 1946 anthology Writers of Today; but ultimately that's just a reprint of his 1944 article from Penguin New Writing, " The Poetry of Edith Sitwell."

Osbert Sitwell was a huge influence on Reed's development as a poet and writer: he brought Reed under his wing introduced the young poet to what must have previously seemed like an unreachable circle of writers and musicians, actors and artists. Sitwell was chairman of the Society of Authors when Reed was given a bursary to support his writing in 1945: £200 per year for three years. Reed lunched with Edith Sitwell in London at Osbert's urging; Osbert sent Reed to visit Violet Gordon-Woodhouse during the Blitz.

Reed reviewed the second volume of Osbert's autobiography, The Scarlet Tree, for The New Statesman and Nation on August 31, 1946. A self-proclaimed Kleinian, the memoir probably helped cinch Reed's views on the influence of childhood on the authors and novels of the mid-twentieth century. Reed devotes a full page to Sitwell:

BOOKS IN GENERAL The Scarlet Tree, by Osbert Sitwell (Macmillan, 15s.) has an advantage over many autobiographies: it is written by an experienced novelist, who is here turning into art a richer material than he has used elsewhere, and who is partly employing the novelist's craft in shaping it. Who else but a novelist could contrive the checks upon racing Time which we find in this book, the disposition of a heavy emphasis here, a light one there, the holding back of an explanation till "later," the anticipations, the use of suspense, and above all the carefully-timed entrances and re-entrances of the characters? In biography Sir Osbert Sitwell's contrivances would be intolerable; in autobiography they are a blessing: There is something else which strikes one as one compares this book with a novel: because this is life, and not fiction, certain characters with traits which would in a novel be unacceptable outside the broadest farce are acceptable here. Where, in a novel, after our acquaintance with a character, has extended over several hundred pages, could we believe the, statement that he had "invented a musical toothbrush The Scarlet Tree which played 'Annie Laurie' as you brushed your teeth, and a small revolver for shooting wasps?" Sir George Sitwell, the author's father, is said to have invented both of these; perhaps they worked; but we should be rather incensed by the idea in a novel. So that, throughout, The Scarlet Tree has all the virtues of a large-scale discursive roman fleuve, with none of the restrictions of probability that a serious novelist has to impose on himself.

There is plenty to make the reader laugh in this autobiography; there are many exquisite comic miniatures where absurdities are highly packed into a small space, as in the account of two of the author's elder cousins:

But, in fact, they got on well together, in spite of their differing so often in the opinions they put forward. In the past, however, certain disputes had taken place occasionally, so that each sister has pasted somewhere on every article of furniture belonging to her — whether it were an oak chair, a table, a bronze, a chased-silver photograph-frame, or merely a Japanese vase full of last year's pampas-grass — a label, which bore on it in clear, black, decisive letters, admitting of no question, the name FLORA or FREDERICA. Thus, if either of them decided of a sudden to quit, she could accomplish it immediately, departing with her own belongings and without the possibility of further discord. But in its major intention The Scarlet Tree is a tragic, not a comic, book. Things which were treated comically, or hinted at in a non-committal tone neither of comedy nor of tragedy, in Left Hand, Right Hand, begin to develop more darkly here. And yet it is part of the novelist's art that the most lingering impression of the book is a quality not of darkness but of light. Indeed, descriptions of light are part of its scheme: Were is along Proustian meditation by the author while, as a child, he lies in bed at daybreak and feels the day increasing behind the shutters; there is another, a little later in life under the title of A Brief Escape into the Early Morning. Yet bathed in light though the book is — and one wishes that Mr. Piper's pictures had turned occasionally aside from their excruciating melodramatic gloom to try and recapture a little of this — the book is principally a picture of tragic childhood, of infant vitality, exuberance and perspicaciousness flickering against deepening shadows of older futility. If, in fact, one or other of this distinguished family of writers has sometimes seemed, in print, a little too easily indignant or provoked; if they have had less difference to the censure which all writers of genius sometimes evoke than their admirers would like to see in them: then perhaps we find the reasons in The Scarlet Tree. But while the author employs much candour in speaking of his upbringing, he leaves it to his readers to make, if they choose, explicit comment on it. A critic may perhaps be allowed to describe it as horrible and appalling. No one can contemplate without misgiving those pathetically awful small children who are allowed a wholly uninhibited expression of their impulses, and who early realise with the natural cunning of children that there are no limits to how far they can go. But the opposite of this is scarcely better: the children rigorously subjected to the sort of well-meant cruelty — a complete divorce of ends and means — which permitted Sir George Sitwell always to insist that his children should do the exact opposite of anything they showed pleasurable inclination towards.

Yet it is not to be imagined that Sir Osbert presents his father in the familiar guise of an Edward Moulton-Barrett [father of Elizabeth Barrett-Browning]. The most subtle and original thing in this book is the suggestion it gives that all early development is haphazardly circumstanced: it is a crawl through a garden wilderness where the cruellest briars and the largest fallen branches which impede the way pave also once had their struggles for existence and growth. It is a wise sense of this that persuades, Sir Osbert in talking of his own upbringing to open out for us a remoter vista: the childhood of his father.

Here, having watched the development of a character, as seen by a child, a son, the reader may ask why my father so continually insisted on being in the right, to the extent that if events proved to him that he had been wrong, and he could no longer avoid such a conclusion, he had to fall ill... The reason, I deduce, must be sought a long way back, in the 'sixties of the previous century when he was a small child... I used to think that his disposition and his whims, sometimes so delightful and removed from reality, at others so harsh, and, indeed, hateful, were the result of his having been brought up entirely by women since the age of two, when, as we have seen, he succeeded his father; were rooted in the circumstance that he had never been controlled or disciplined or contradicted, and that, further, he had inherited an ample fortune at the age of twenty-one, finding himself, in fact, one of those local princes of whom Meredith tells us in The Ordeal of Richard Feverel. But my father had always maintained that his mother, though, by the time I knew her, gentle and on occasion almost indulgent, had not — for she was one of a family of five daughters — understood how a boy should be managed, and had treated him — of course without meaning to do so, for she was utterly devoted to him — with severity, and sometimes almost with cruelty.... And I have come to believe that this was true since I found in 1938 in the library at Renishaw a forbidding-looking account-book, short and thick, with an ecclesiastical clasp of brass. I opened this volume at random, and my eye lit on a page, not devoted to figures, on which were written, in a round, childish hand, very different from that which I knew, and yet even then recognisable, the words "George naughty again Jan. 20th." From the character of the letters, he plainly could not have been more than six or seven when obliged to enter that sentence. Underneath was inscribed in my grandmother's beautiful, flowing hand, "George naughty a second time Jan. 20th." There are many variations in the book on the theme of semi-conscious paternal bullying; and there is a good deal of its painful counterpart, semi-conscious maternal indifference. Lady Ida Sitwell could also be cruel — and in a perhaps more despicable way — but a part of her was all on the side of kindness, and it seems to have been easily played on by the unscrupulous; but the actions of her life, according to the testimony of a son whose completely affectionate attitude to her cannot be questioned, were principally dedicated to the pursuit of "fun"; and to such a temperament as hers, children provide little. Where it was most craved, therefore, her kindness was something least forthcoming. Yet there is an element of "attack" in Sir Osbert's account of his upbringing, though some things — among them his mother's attitude to his sister — cannot be treated with complete equanimity; but about his own injuries he has come to that state of comparative calm (it is nothing so smug as forgiveness, which: is always rather an indecent gesture on the part of a human being) the attainment of which is part of every artist's task.

This volume covers ten years of the young Osbert's life. It includes the deepening of certain threatening shadows at home, the whole of his school life, accounts of London and Scarborough, and his first glimpses of Italy. On its more sombre side it includes, too painfully for isolated quotation, a brief, horrifying scene with an unscrupulous private tutor, one of those dramatic moments of suspense and foreboding which are again, a hint of the art of the novelist — points of significant detail which crystallise a whole phase of life. The accounts of the schools — a day, school at Scarborough, two private boarding-schools, and Eton — are written not without ferocity. But there is more than that: we are used to people writing satirical, indignant or regretful accounts of their schooldays; with rare exceptions, there seems to be little reason for them to write otherwise. Sir Osbert employs satire and indignation — Bloodsworth in particular, appears not to have been far short of a torture-chamber — but he sees deeper than, these instruments by themselves will allow a man to see: he uncovers a process of malformation, permanent or temporary. Esce di man di Lui l'anima semplicetta; but, the simple little soul returns from his second world severely misshapen:

The school restored to my parents a different boy, unrecognisable, with no pride in his appearance, no ability to concentrate, with health impaired for many years, if not for life, secretive, with no love of books, and an impartial hatred for both work and games, with few qualities left and none acquired, save a love of solitude and a cynical disbelief, firmly established, in any sense of fair play or prevailing standard, of human conduct. He has no hesitation — why should he have? — in making clear who or what helped to undo this mischief. Principally, himself; but some things in addition which were denied to many of his companions. There was the calm beauty of Renishaw; there were his own growing apprehensions of the things man has formed out of the mess of life; there was Italy. It is a tempting preciosity to say that the Englishman's education and sensibility are incomplete without Mediterranean experience. It is also a palpable falsity; they are equally incomplete without experience of the South Seas, China, Russia and India. But to the English artist (to say nothing of anyone else) Italy has a strange power of benediction — more potent and residual perhaps when no attempt is made by the Englishman to externalise, its beauty into art; Sir Osbert is not, of course, the Englishman Italianate who incurred and deserved Elizabethan censure; but now that the centre of diabolism seems temporarily to have moved to Paris, it is delicious to find the magic of Italy restored in pages that are among the best in the book.

The remarkable achievement of The Scarlet Tree is its avoidance of an episodic character. No writer of our time — unless perhaps Mr. William Plomer in his own autobiography — has shown greater delight in the unusual and absurd sideshows of human behaviour, or more tenacity in storing them up, for future reference. But in The Scarlet Tree anecdotes are used only as occasional illustration to the general succession of the "movements" of life. It is not a book which over-emphasises detail at the expense of form: the whole work, of which this is said to be a quarter (though one prefers to hope that it will be but an eighth or a twelfth) promises to be a masterpiece of controlled expansiveness; it has already a quality of humorous and urbane magnificence, and a romantic lyricism rare in contemporary prose. It is worth while remembering that this is achieved in spite of rather than because of the author's native background. Our times provide us with a new opportunity for snobbism which we eagerly grasp at; with a gracious smile we accept socialism, and with a wider one we indicate how much we are giving up. The author of The Scarlet Tree knows all this; and he is at pains to show in these Edwardian chapters what sterile dramas could enact themselves, what futile games be played, against the background of Renishaw. He insists that the notable qualities of himself, and of his brother and sister, are qualities of mind. These they brought with them; they did not find them there.

Henry Reed Who could read all that and not put both Left Hand, Right Hand and The Scarlet Tree on their wishlist?

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

News of the Moby-Dick "Big Read" has reminded me just what a fan Henry Reed was of Melville. Readers such as Tilda Swinton, @stephenfry, Simon Callow (Simon Callow!) and even Prime Minister David Cameron are giving voice to all 135 chapters of Moby-Dick, posted online over 135 days. And not just celebrities are reading: there will be episodes from " schoolchildren and careworkers and fishermen," according to author Philip Hoare, who co-created the project with artist Angela Cockayne.

Henry Reed, of course, famously adapted Moby-Dick into a play for the BBC's Third Programme (starring Sir Ralph Richardson as Ahab), first broadcast on January 26, 1947. A second production was organized and broadcast on Radio 4 in 1979.

Reed also reviewed a new edition of Melville's Billy Budd for the "Books in General" column in the New Statesman and Nation on May 31, 1947. He had as much to say about Moby-Dick as he did for Billy Budd. Spoiler alert! If you haven't read it:

BOOKS IN GENERAL To discover and to read, in the midst of a batch of contemporary novels, Herman Melville's last—and hitherto all but improcurable—story, Billy Budd, Foretopman* is to find oneself faced with a dazzling revelation of, how many virtues modern fiction has lost or discarded. Billy Budd is, in the first place, a good story, a "plain tale," or so it appears; it is well written, and the uncertainties of its manuscript text do not greatly matter; it has a hero and a villain who are carefully designed to dramatise the extremes of goodness and badness. And more striking than anything else to the reader of to-day are its discursive comments on character, the generalisations about psychology evoked by the development of the story itself. One cannot doubt that in modern novelists the capacity for moral commentary still exists; but it is a capacity they more and more tend to suppress. When Melville blesses one of his characters with "natural depravity," it seems to him perfectly reasonable to enlarge on the implications of this:

Not many are the examples of this depravity which the gallows and jail supply. At any rate, for notable instances—since these have no vulgar alloy of the brute in them, but invariably are dominated by intellectuality—one must go elsewhere. Civilisation, especially if of the austere sort, is auspicious to it. It folds itself in the mantle of respectability. It has its certain negative virtues serving as silent auxiliaries. It is not going too far to say that it is without vices or small sins. There is a phenomenal pride in it that excludes them from anything... mercenary or avaricious... In short, the depravity here meant partakes nothing of the sordid or sensual. It is serious but free from acerbity. Though no flatterer of mankind, it never speaks ill of it.

But the thing which in eminent instances signalises so exceptional a nature is this: though the man's even temper and discreet bearing would seem to intimate a mind peculiarly subject to the law of reason, not the less in his soul's recesses he would seem to riot in complete exemption from that law having apparently little to do with reason further than to employ it as an ambidexter implement for effecting the irrational. That is to say: toward the accomplishment of an aim which in wantonness of malignity would seem to partake of the insane, he will direct a cool judgment sagacious and sound.

These men are true madmen, and of the most dangerous sort, for their lunacy is not continuous, but occasional; evoked by some special object; it is secretive and self-contained, so that when most active it is to the average mind not distinguished from sanity, and for the reason above suggested that whatever its aim may be, and the aim is never disclosed, the method and the outward proceeding is always perfectly rational.

Now something such was Claggart... At first Billy Budd seems a curious book to think of Melville writing; but much criticism has prepared one for its late-Shakespearean calm. In the crowding tumult of Moby Dick and the neurotic fervour of Pierre, Melville seems to have burned himself out; or, if the fire remained, it was damped down by popular neglect or censure or incomprehension. In the Oxford History of the United States, Professor Morison of Harvard says that "not until 1851 did a distinctive American literature, original both in form and content, emerge with Moby Dick"; and it is rarely that a literary landmark is detected until it has been left a good way behind. Wretched and perplexed Melville struggled on, as we know, with a few other novels and short stories, and then quietly abandoned prose writing. Almost forty years after Moby Dick, and within a year or so of his death, he produced Billy Budd.

In style and mood it is as far from Moby Dick as it could be. In the earlier book one remembers, side by side with its exact realism, rhapsody also, and its fine, rhetorical, probable conversations. There is neither rhetoric nor rhapsody in Billy Budd. And in Moby Dick Melville is continually forcing you to look, beyond the lives of his characters, at Life itself. For Melville, as for Ahab, the battered Pequod is an ambiguous vessel: its mixed crew are "an Anacharsis Clootz deputation from all the isles of the sea, and all the ends of the earth, accompanying Old Ahab in the Pequod to lay the world's grievances before that bar from which not very many of them come back." It is "an audacious, immitigable and supernatural revenge" that Ahab intends in his pursuit of the white whale.

...All that most maddens and torments; all that stirs tip the lees of things; all truth with malice in it; all that cracks the sinews and cakes the brain; all the subtle demonisms of life and thought; all evil, to crazy Ahab, were visibly personified, and made practically assailable in Moby Dick. He piled upon the whale's white hump the sim of all the general rage and hate felt by his whole race from Adam down. To Ahab "all visible objects are but as pasteboard masks." And he infects the crew with his unearthly feeling for Moby Dick in a way that Ishmael, the story-teller, hesitates to define:

What the White Whale was to them, or how to their unconscious understandings, also, in some dim, unsuspected way, he might have seemed the great gliding demon of the seas of life—all this to explain would be to dive deeper than Ishmael can go. But he does at once go deeper; and the chapter on whiteness is perhaps the "deepest" thing in the book. It is a chapter about the beauty and the terror of white objects, animate and inanimate: "and of all these things the Albino whale was the symbol. Wonder ye, then, at the fiery hunt?"

By these, and by many other touches, Melville accretes to his realistic story an imprecise and terrible other story. The actual whale is not, he assures us, an allegorical creature he has made up himself. The whale itself is real enough; it is in the nature of Melville to see an object or creature accurately before the object takes on an ambiguous cast. He sees the whales' nursery, can mean to him:

And thus, though surrounded by circle upon circle of consternation and affrights, did these inscrutable creatures at the centre freely and fearlessly indulge in all peaceful concernments; yea, serenely revelled in dalliance and delight. But even so, amid the tornadoed Atlantic of my being, do I myself still for ever centrally disport in mute calm; and while ponderous planets of unwaning woe revolve round me, deep down and deep inland there I still bathe me in eternal mildness of joy. Object first; simile, some distance after. Melville's mind is free from the allegorical impulse which takes a spiritual theme and impresses objects into the illumination of it. This distinction between allegory and symbolism must not be forgotten, since it is always there. In symbolism the real object is seen first; from it, to adopt a phrase of Mr. T. S. Eliot, a "purpose breaks." This happens continually in Melville; and it is worth recalling that his great creative period coincided with that of Poe, to whom the French symbolist poets were always confessing their debt.

From Billy Budd also, when the tale is completed, a purpose breaks; a simple one, emerging with deceptive quietness. In this tale Melville, at the end of his life, is giving expression to a feeling he has perhaps not before acknowledged or understood. Once more, he comes to understand it by way of real objects and people. It is as if retired within himself, and searching the darkness of experience that lies behind and before him, he draws up from the shadows a perfect image of uncontaminated beauty, nobility and courtesy. We know who provided that image: it was Melville's friend of earlier days, Jack Chase; and it is to him that the new book is dedicated: "To Jack Chase, Englishman, wherever that great heart may now be here on earth or harboured in Paradise." Chase had been captain of the maintop in the frigate United States, in which Melville had served in 1843. He had shone like a bright light in the ugly world that Melville describes in White Jacket; idealised a little, he now appears as Billy Budd. The action is moved back to the days of Napoleonic wars, shortly after the Mutiny at the Nore.

There is little or none of the "transcendental" Melville in the actual language of the book. It is true that the Anacharsis Clootz deputation is once more referred to; and the free merchant vessel from which Billy is impressed into the Navy is called the Rights of Man. But this is a mere glimpse of the book's outer rind; we do not touch that half-whimsical quality again till the very end, when we hear the name of another ship. Billy is forced to serve in a man-of-war. He is what in those days was called a Handsome Sailor. He has a beauty that is praised and adored by the generality of men—and he is not, it may be urgently stated, a pansy. But Billy's grace, as is the way of grace, evokes also from one point an overwhelming malignity. There is among the crew an official of some power called Claggart, whom Melville seems to develop from, the villainous Jackson of his early autobiographical novel Redburn. Claggart is not unaffected by the beauty of Billy's form and character. He perceives it, one might say, much as Iago perceives that of Cassio:

If Cassio do remain,

He hath a daily beauty in his life

That makes me ugly. Claggart, ostensibly affable towards Billy, decides in his heart that he must be done away with. The discernment of the ways and means of such a hate is one of Melville's many profound intuitions; I do not doubt that he could have pursued the origins of such a passion further, for his prose and his poetry abound in astonishingly prophetic hints about the reaches of the unconscious. But none are given here. At school one sometimes dimly recognised something ineffably horrible when one, saw a perverted schoolmaster bullying an angelic-looking boy; Melville allows us dimly to recognise a perversion of much the same kind here. Claggart fabricates against Billy a charge of incitement to mutiny, and reports him to Vere, the captain, a man extreme nobility and perception. Vere is dubious of the charge, and sends for Billy. Billy is afflicted with a stammer—his one defect. When confronted with the charge he cannot speak; he answers Claggart in the only way he knows; he strikes him with all his force, and Claggart falls dead. Vere's sympathies are wholly with Billy; but a trial is inevitable; so are the verdict and the punishment. It is war-time; and the question of mutiny is a real thing, not to be treated lightly. Vere asks what is truth; but dare not stay for an answer. At dawn next day Billy is hanged at the yard-end.

As a character Billy meant a little more to Melville than could be expressed in prose. Billy Budd ends with a rather touching unaccomplished effort to get into Billy's impenetrable mind by way of verse:

But me, they'll lay me in hammock, drop me deep

Fathoms down, fathoms down, how I'll dream fast asleep.

I feel it stealing now. Sentry, are you there?

Just ease these darbies at the wrist,

And roll me over fair,

I am sleepy, and the oozy weeds about me twist. But the story as a whole remains more important than its parts or its separate characters. If we have any doubts about what it "means" to Melville, he puts them to rest by a few more or those touches which, for want of a proper word, I have called half-whimsical Billy dies; "and, ascending, took the full rose of the dawn." The noble Captain Vere is felled shortly after by a musket-ball from a ship which has been re-named the Athéiste. And for years afterwards the spar from which Billy has hanged is kept trace of by the crew; to them, later, "a chip of it was as a piece of the Cross." ...The creator of that and the white whale was to cherish his "ambiguities" to the end.Henry Reed

* Billy Budd. By Herman Melville. Introduction by William Plomer. Lehmann. 5s. The Moby-Dick "Big Read" runs through January, 2013.

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

This blurb appears in a publisher's advertisement in The Spectator for February 18, 1949. It's lifted, according to the byline, from a book review Henry Reed wrote for The Observer, on Gerard Hopkins' translation of selections from Proust (London: Allan Wingate, 1948).

MARCEL PROUST

A Selection from his Miscellaneous Writings

Chosen and Translated by Gerard Hopkins

MARCEL PROUST

A Selection from his Miscellaneous Writings

Chosen and Translated by Gerard Hopkins'We have the charming experience of meeting Proust outside the turmoil of creation, chatting, confiding, preparing... the same character, the same voice, that come through the translation of Scott-Moncrieff come through Mr. Hopkins's no less sensitive versions.' Henry Reed, Observer. 10s 6d net Not only is this the first record I have of Reed reviewing this particular work, but it's actually the first clue I have to any Reed review appearing in The Observer, at any time. Are there more? I bet there are more.

Tracking down a Observer review is going to be difficult. I don't know the date (but we can easily surmise it was sometime in late 1948 or January 1949), and I can't find a library within easy reach that has the paper from the 1940s, either in print or on microfilm. I'll check Book Review Digest, etc., and see if I can pinpoint it.

(And what do we have, here? In The Guardian News & Media Archive catalog, is a record for a photograph of "Reed, Henry: Radio," in a file for " Prints by Guardian/Observer photographers.")

|

1529. Sackville-West, Vita. "Seething Brain." Observer (London), 5 May 1946, 3.

Vita Sackville-West speaks admirably of Reed's poetry, and was personally 'taken with the poem called "Lives," which seemed to express so admirably Mr. Reed's sense of the elusiveness as well as the continuity of life.'

|

For this edition of "Reed Reviews" we dig up Henry Reed's "New Novels" column from The Listener for February 6, 1947. Reed reads for us a short story collection by Sid Chaplin, a translation of Camilo José Cela's La Familia de Pascual Duarte, and the first English publication of Jean-Paul Sartre's The Age of Reason ( L'âge de raison), the first volume of his existentialist trilogy, The Roads to Freedom:

New Novels

New Novels

The Age of Reason. By Jean-Paul Sartre.

Translated by Eric Sutton. Hamish Hamilton. 10s.

Pascual Duarte's Family. By Camilo J. Cela.

Eyre and Spottiswoode. 7s. 6d.

The Leaping Lad. By Sid Chaplin.

Phoenix House. 8s. 6d.M. SARTRE is primarily a brilliant artist. He is secondarily a philosopher, one of the leaders of a more or less new school of thought. It is therefore a great pity that in England we should have read so much about his philosophical ideas before we have had much chance of reading his stories and plays; and it is probably a further pity that his ideas should for the most part have been first expounded by antagonistic critics. His plays, 'Les Mouches', 'Huis-Clos' and 'La Putain: Respectueuse', need nothing in the way of exposition; they make their points unaided, and their points are clear ones. With The Age of Reason I feel far less sure; it is the first volume of a trilogy called 'Les Chemins de la Liberté', and though it is a book of quite extraordinary power it cannot be thought of very easily as a work by itself, since at the end of volume one, the reader is likely to be left still baffled by M. Sartre's theme, and by his terminology. The semantic of abstract nouns is almost always so eroded (as Professor Hogben would say) that they need continual re-definition. And I am far from certain what M. Sartre means either by freedom or by reason. I have uneasily assumed from the story itself, and from things I have picked up here and there, that Mathieu, the hero of the book, who is questing for freedom, is out to attain a state of mind and a condition of will where he will be free to act without being influenced by the image he creates in the minds of others. As a child he has vowed to himself: 'I will be free'. At the end of the first volume we find him saying to himself that he has attained the age of reason, and the meaning of this is, so far, even less clear; he means in one sense that his adolescence is over; but one is perplexed by the fact that his attainment of the age of reason, whatever it be, is principally caused by an act performed by someone else. This is brought about as follows.