|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

Posts from February 2009

|

|

|

27.4.2024

|

Continuing to peck through library archives and special collections, I've found a letter (or letters) from Henry Reed, written to Denys Kilham Roberts, in the Historical and Literary Manuscript Collections at the University of Iowa. From the index to their finding aids:

ROBERTS, DENYS KILHAM. Papers of Denys Kilham Roberts. 1.5 ft. Correspondence to and from a British writer of the 1920s and 1930s. MsC828. Iowa's index doesn't go into greater detail, but the library catalog does: "Roberts, Denys Kilham, 1903-1976. Correspondence, 1930-1964," with letters from (and/or to?): E.M. Forster, David Gascoyne, Wilfrid Gibson, Robert Graves, Herbert Read, Edward Sackville-West, Siegfried Sassoon, George Bernard Shaw, Julian Symons, and Evelyn Waugh, among many others (Reed included). A summary describes the collection:

Discussing his publications and those of his correspondents; concerning a BBC program titled "Catchword Songs"; soliciting literary contributions to various publications; encouraging other writers.

Roberts compiled and edited numerous poetry anthologies during the 1930s, '40s, and '50s, including the five-volume The Centuries' Poetry (1938-1942). He also served as Secretary of the Society of Authors during the 1940s, and edited Penguin Parade, a showcase of "New stories, poems, etc. by contemporary writers," between 1937 and 1945.

At first I was hopeful that Roberts may have solicited a poem from Reed for Penguin Parade, but looking at all the available covers in AbeBooks turns up nothing. A quick look at the bibliography, however, reveals Roberts listed as one of the editors of the journal Orion: A Miscellany, to which Reed contributed twice: his poem "King Mark" ( 1945), and the essay "Joyce's Progress" ( Autumn, 1947). It would seem logical that Reed's correspondence would be in regards to one of, or both of, his Orion appearances. Alas, Iowa provides no dates.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

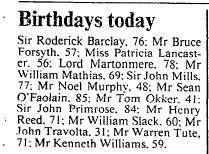

Beginning in 1973 when he was 59 years old, the Times (London) included Henry Reed in the daily birthday announcements, in their " Court and Social" page. This continued up until his death, in 1986, at the age of 72 (with the exception of 1979, when the Times was in the midst of a year-long newspaper strike). In honor of the 95th anniversary of Reed's birth, here's his announcement from February 22, 1985:

(John Travolta's birthday, we note, is actually Feb. 18!) If you're interested in such things, you can see a list of folks born on February 22nd on Wikipedia.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

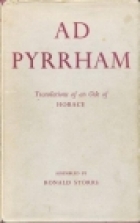

It is always encouraging to find someone who has an odder pastime than yourself. Often, it's uncomfortable when I finally have to break down and tell certain people what I'm working on—that I collect old book reviews written in the 1940s, and that one side of my living room is lined with shelves of photocopies stuffed into manila envelopes. And then I come across Ronald Storrs. From a book review for Storrs' posthumously published Ad Pyrrham: A Polyglot Collection of Translations of Horace's Ode to Pyrrha (1959):

For many years before his death in 1955 the diplomatist and statesman Sir Ronald Storrs made an avocation of collecting 50 translations of Horace's Pyrrha ode ( Carm. 1.5). His collection, which by 1955 comprised several hundred versions, has since, under the supervision of Sir Charles Tennyson, increased to four hundred and sixty-three. From these Sir Charles has chosen for the present volume sixty-three English translations, twenty French ones, fifteen Spanish, thirteen German, twelve Italian, and twenty-one in other languages, including a Turkish prose version, several in various Slavic and Scandinavian tongues, a distressing Latin rewriting by a seventeenth-century German professor extolling his own connubial felicity, and (to the reviewer) impenetrable renditions into Maltese, Hebrew, Lettish, Hungarian, Finnish, and Welsh.

That, my friends, is what I call a collector. The text contains a total of 144 versions of Horace's famous poem (six of which are from Latin into Latin), from 25 different languages.

Ode to Pyrrha What slender youth bedewed with liquid odours

Courts thee on roses in some pleasant cave,

Pyrrha? For whom bind'st thou

In wreaths thy golden hair,

Plain in thy neatness? O how oft shall he

On faith and changèd gods complain: and seas

Rough with black winds and storms

Unwonted shall admire:

Who now enjoys thee credulous, all gold,

Who always vacant always amiable

Hopes thee; of flattering gales

Unmindful? Hapless they

To whom thou untried seem'st fair. Me in my vowed

Picture the sacred wall declares t' have hung

My dank and dropping weeds

To the stern god of the sea. Not only is Storrs' book uniquely singular in scope, but is of interest to our particular endeavor, as well. In what I believe is a preface written by Charles Tennyson, Storrs' editor, we find the following mention:

The French and German versions have been chosen by Mr. Richard Graves, a lifelong friend of Sir Ronald's, who is himself a distinguished translator, and Mr. Henry Reed has very kindly chosen the examples in Italian.

Reed, I need not remind you, went to university on a Latin scholarship, and is famous for twisting the words of Horace ( Carm. 3.26) for the epigram to "Naming of Parts." I'll be adding Ad Pyrrham to my shortlist of items to track down at the nearest library, at which time I promise to post an updated photograph of my living room.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

I came across a curious reference this evening, to a " Collection, 1924-1983," with a laundry list of associated names: J.R. Ackerley, Brigid Brophy, Edward Carpenter, Rena Clayphan, G. Lowes Dickinson, George Duthuit, Roy Broadbent Fuller, Sir John Gielgud, Henry Festing Jones, James Kirkup, Francis Henry King, Rosamond Lehmann, Desmond MacCarthy, James MacGibbon, Sean O'Faolain, Sir Herbert Edward Read, Henry Reed, and Vita Sackville-West. But no location, no source, and only a partial title. Obviously the record was uploaded from a library catalog, somewhere. But where?

I had a feeling the people on the list had something (or someone) in common, but I couldn't puzzle it out. I searched the Location Register. I searched for library and .edu holdings. And then I suddenly remembered my WarGames, where Lightman (Matthew Broderick) is counseled to "go straight through Falken's Maze," the first game on his list. Ackerley. Joe Ackerley is the first name in the list. Protovision, I have you now.

I don't know why I didn't think of it straight off: an easy search of WorldCat turns the collection up, at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin:

Following the holdings library on WorldCat whisks you into the University of Texas Libraries' catalog record for " Ackerley, J.R., Collection 1924-1983". And there, among the cardboard boxes filled with manila folders and acid-free envelopes, are four letters from Henry Reed to Ackerley, dated from 1937 to 1942. During those years, Ackerley was editing the BBC's magazine, The Listener, where Reed published his first poems. But wait, there's more!

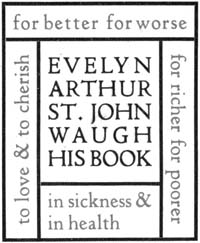

Led by the tantalizingly linked author field " Reed, Henry, 1914-1986" in the collection's catalog record, we discover that the Ransom Center's book collection has quite a few editions of Reed's, including signed copies of A Map of Verona originally presented to Ackerley and Edith Sitwell, as well as Evelyn Waugh's personal copy (with bookplate). I can't begin to tell you how marvelous it is that the Texas Libraries thoughtfully provides a "Bookmark Link" feature: static URLs for all their records.

The Ransom Center's Ackerley collection isn't detailed in their online finding aids, but at the end of the maze I also turned up a copy of a letter to Reed in the correspondence files for Alfred A. Knopf.

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

What else should I call the tale of how Henry Reed almost became a scriptwriter for a 1970s biopic on King Abdul Aziz Al Saud? It's a strange story of anonymous sheikhs, the clash of egos in the film industry, disappearing money, and mistaken identity.

In 1975, the director Joseph Losey was approached with an offer to make a feature film about the life of Ibn Sa'ud, the first ruler of Saudi Arabia. Funding for the project was to come from an anonymous source, negotiating through a firm of London solicitors.

Losey hired Barbara Bray to perform research, and to translate. The Algerian writer, Kateb Yacine, provided a script in French, but his efforts proved disappointing. Negotiations were made with writers Ring Lardner, Jr., and Robert Bolt, but Lardner wanted too much money, and Bolt was "too indoctrinated with Lawrence." Finally, a script was ordered from Franco Solinas, who had previously worked on Losey's Mr. Klein. By now, several years have transpired, and it is at this point in the story that Reed makes his appearance. From David Caute's 1994 biography, Joseph Losey: A Revenge on Life (p. 455):

Now a fatal row blew up. Patricia Losey had been translating Solinas's pages from the Italian as they arrived. Barbara Bray, who didn't appreciate Losey's habit of 'smuggling' his wife in to the work she herself was engaged on, suggested that the script should be translated into English by the poet and radio playwright (Prix Italia, 1951) Henry Reed, who was also the translator of Leopardi and Ugo Betti. The solicitor Peter Stone duly informed Losey that his clients wished to engage 'a first-class literary translator...' Losey was furious: 'I was amazed and appalled at the brutality of your libel by implication of Patricia's work...' To make matters worse Losey persistently referred to Henry Reed as 'Herbert Reed', i.e. the art critic, Sir Herbert Read. Having read 'Herbert Reed's' translation, he declared it inferior to Patricia's: 'I cannot begin to describe to you my rage and perplexity... [your] insensitivity and discourtesy... after Don Giovanni I am quite sure that Patricia's name will be far more known to the mass audiences that Herbert Reed's [ sic].' Worse was to come: the principals put the entire project, plus finance, in the hands of London-based Palestinian entrepreneur Naim Atallah, who promptly dropped Losey.

I was unsure how Barbara Bray might have known Reed, apart from his translations. Then I came across this Wikipedia stub. Bray had been a script editor at the BBC in the 1950s, until she became involved with the playwright Samuel Beckett and moved to Paris in 1961, where she became a well-respected translator, herself.

Ibn Saud was never made, and Solinas's script remained unpublished until after his death in 1982.

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

A couple of years back, I started using Magnolia to manage my bookmarks for links to Reed-related webpages: news items, library collections, biographies of other poets and writers. Since then, I had created over two hundred bookmarks, with descriptions and associated tags.

You probably hadn't heard, but on January 30th of this year, Magnolia suffered a catastrophic loss of user data, and backups. "This is just to say," goes William Carlos Williams, "that I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast." To their credit, the site has since provided several data-recovery tools, one of which managed to find cached examples of 197 of my bookmarks. The most recent items are still Missing in Action, as it were.

This morning I imported my recovered bookmarks into Delicious. You can see the new linkroll in the lower → right-hand ↓ sidebar of this page, under the "Marginalia" heading. I still need to tweak the styles, but it works!

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

Henry Reed was the radio critic for the New Statesman and Nation for five months, writing the "Radio Notes" column for the Arts and Entertainment section. Between October, 1947, and February, 1948, Reed's byline appears after seventeen reviews of various music programs, interviews, debates, speeches, and plays.

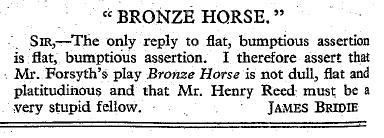

One such review resulted in a letter to the editor from none other than James Bridie, the Scottish playwright and screenwriter. Among his many film credits, Bridie worked on the scripts for no fewer than three films with Alfred Hitchcock, including The Paradine Case, in 1947.

In his January 31, 1948 "Radio Notes" column, Reed comments on an adaptation of The Bronze Horse, recorded previously and broadcast on Friday, January 16, on the BBC Third Programme:

Dull, verbose and platitudinous as a play, Mr. James Law Forsyth's Bronze Horse was given a production of unparalleled variety and magnificence by M. Michel St. Denis. It set a new standard for radio, and one hopes resident producers will not ignore it, for it suggested space and perspective in a way one had thought impossible on the air. The actors responded to the detailed drilling, and seemed to have overcome that boredom which usually sets in among them if a play is rehearsed for more than a day and a half. Mr. Ralph Truman and Mr. Paul Scofield were outstanding; I hope we may hear more of Mr. Scofield than we have hitherto.

Here is Mr. Bridie's letter to the editor, from the January 31 New Statesman (p. 96):

Bridie obviously held Forsyth in high regard, as a playwright and a fellow Scot. Reed apparently declined to respond. As luck would have it, Bridie's letter appeared on the same day as a letter from Mr. Hans Redlich, to whom Reed did reply.

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

Today we have something truly special: Henry Reed's review of Eliot's Four Quartets, from the December 9, 1944 issue of Time & Tide. The article is unsigned, but Reed is identified as the author the following month, in Notes & Queries ("Memorablia," 13 January 1945, p. 1).

Reed draws his title from the dedication of The Wasteland, in which Eliot calls Ezra Pound il migglio fabbro, "the better craftsman". Eliot lifted the phrase from Canto 26 of Dante's Purgatorio, wherein the Provençal troubadour Arnaut Daniel is named the best craftsman of the mother tongue.

Such high regard for Eliot's craftsmanship could almost be considered ironic, given that Reed won a 1941 New Statesman contest with "Chard Whitlow: Mr. Eliot's Sunday Evening Postscript," a parody which manages to blend the styles and mock the sentiment of both Burnt Norton and East Coker. (When East Coker was published in 1940, the first thing Reed did was post a copy to his former professor, Helen Gardner.) But Reed's skill for imitation only belies a deeper admiration, even worship. In fact, many of the reviewers of Reed's first volume of poetry, in 1946, would accuse him of being too indebted to Eliot.

Il Miglior Fabbro Four Quartets: T.S. Eliot. Faber. 6s.

it does not disquiet me that there are passages in these four poems that I still do not understand, for whenever I read them, as I do often, the wonderful varied power of the language they employ holds me completely a victim, and I do not mind the uncertainties. Nor does it distress me that the particular religious inflection which their author intends the poems to have comes from a religion which I no longer find myself trying to believe in; for even if the things which Eliot says were not also "true in a different sense", I think that the alternating gentleness and forcefulness of the voice that is speaking would completely suspend my disbelief. Perhaps it is the gentleness of the voice that is the real magic; the agonized gentleness which we do not hear since Tennyson, whom Eliot calls the saddest of English poets:

Calm is the morn without a sound,

Calm as to suit a calmer grief;

And only through the faded leaf

The chestnut pattering to the ground. That, somehow, is a voice one can trust. So is this voice:

The brief sun flames the ice on pond and ditches,

In windless cold that is the heart's heat,

Reflecting in a watery mirror

A glare that is blindness in the early afternoon.

And glow more intense than blaze of branch, or

brazier,

Stirs the dumb spirit. After the exquisite language of these poems, whatever one tries to say by way of criticism or analysis sounds uncouth. One has also the feeling that one is slightly off the point, because they are poems which can be communicated only in their own words. But since they are difficult and elusive, it is necessary for a critic to say what he thinks they are about. Time is their theme. (That is not quite true, but it is as near as one will get.) They aim at discovering a means of facing time; at discovering an attitude towards time which shall be something different from a subservience to the passing of the years; at discovering a capacity for thinking of the present moment not as a bridge between past and future, but as a point in an eternal pattern. To conquer time we have only one weapon given us—time. And at this point one wonders if one would not do better to say the poems are about life rather than about time.

Eliot's examination, or quest, begins simply (so far as he is ever simple) and hesitantly in Burnt Norton with one particular "aspect" of time; the highest complexity and difficulty are reached in the second and third movements of The Dry Salvages; the problem is solved in Little Gidding. The over-all drama of the quest is stressed by the sequence of the four symbols, air, earth, water and fire, which the four poems suggest. The intensity of the poem increases from the quiet of Burnt Norton, through the disturbances of East Coker to the tumult of The Dry Salvages, and relaxes to a final tranquillity at the end of Little Gidding. In each of the separate poems (which all follow the same structural design) there is a separate drama of crescendo and diminuendo.

In Burnt Norton we are given a fairly easy exercise in perception: Eliot recalls to us that not uncommon moment when the common sequence of minute after minute seems suspended, when two kinds of consciousness seem to cross. This may happen in a variety of ways; perhaps Proust encountered the same thing when he tasted the madeleine; for Eliot, in this first poem, it is the coincidence of a vision of what is, and a vision of what might have been. What is, is a deserted garden and a drained pool; what might have been, is the shrubberies full of children's voices, and the pool filled with water. Both moments seem equally actual: the double moment of "actuality" is reality, a state we cannot bear for long; it is a moment quickly to be seized and quickly gone, a "hint" of a greater experience. That experience, we are told later, is the intersection of eternity and time at the Incarnation.

The opening of this first poem presents a way into the problem of time; the core of the rest of it is the effort to break free from—

the enchainment of and future

Woven in the weakness of the changing body. East Coker is a study of the onset of age, and of the discovery that age, contrary to all the promises, brings neither wisdom nor the solution to our tragedies:

We are only undeceived

Of that which, deceiving, could no longer harm

. . . .

The only wisdom we can hope to acquire

Is the wisdom of humility: humility is endless. In this poem the pattern as distinct from the sequence of life is once more emphasized; and in this pattern the dead also are involved. This is an advance from the moment in the garden in Burnt Norton. The poet desires:

Not the intense moment

Isolated, with no before and after,

But a lifetime burning in every moment

And not the lifetime of one man only

But of old stones that cannot be deciphered. In The Dry Salvages, the themes of eternity and death are announced. The climax of this poem is an echo, one gathers, of Krishna's words to Arjuna in the Gita; but it reminds us also of "Make perfect your will", and of "Take no thought for the harvest, but only of proper sowing." It is an admonishment—significant only to the religious man, perhaps, but not beyond the appreciation of others—to live each moment, regardless of past and future, as if it were the moment before death.

O voyagers, O seamen,

You who come to port, and you whom bodies

Will suffer the trial and judgement of the sea,

Or whatever event, this is your real destination. The movement towards the faith of Christianity is already clear; and it becomes clearer still in Little Gidding. At the end of The Dry Salvages, we are told where our duty lies: in "prayer, observance, discipline, thought, and action." In Little Gidding we go to a place where "prayer has been valid", where the Holy Ghost has once descended to flame in men's hearts. In this poem the themes of the earlier poems are resumed and rounded off. We are left with the Christian choice: to be redeemed from the fire of hell by the flame of Pentecost. The fifth movement of this poem is a masterpiece of concentration; in it the poet reminds us, in a way that usually only the allusions of music can, of all he has had to say. Above all, he tells us that what he has to say is not anything new. He has already said in East Coker that all he can do in his poetry is to rediscover what has been found and lost before. That is all one will do in life itself, however, one goes about it.

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|