|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

Posts from September 2008

|

|

|

27.4.2024

|

It's always bothered me that Henry Reed's entry in Contemporary Authors lists among his accomplishments: 'Contributor of poetry and criticism to periodicals, including Poetry, New Yorker, Theatre Arts, Nation, Newsweek, and Time.' Articles and reviews which mention Reed, his poetry or translations, do appear in all these publications, but as far as I know, he never authored a poem or piece of criticism for any of the listed periodicals. It's as though some editor lazily flipped through a subject heading card file, or ran a keyword search for his name.

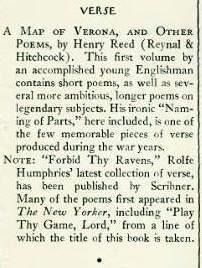

Reed comes up several times in the New Yorker, when his adaptations of Ugo Betti were staged on Broadway in 1955 and 1982, and there's a review for his translation of Buzzati's Larger Than Life, in 1968. So I was surprised to find a reference to " Brief notes on works by Henry Reed and Rolfe Humphries" in a bibliography of the writings of Louise Bogan.

Bogan was poetry editor of the New Yorker for 38 years, from 1931 until her retirement in 1969. But it was difficult for me to believe that I could have missed something as huge as a whole book review for Henry Reed. As it turns out, the American edition of Reed's poetry collection, A Map of Verona, and Other Poems, receives mention in the "Briefly Noted" portion of the Books column in the New Yorker issue for November 22, 1947 (p. 140):

Two sentences barely even qualify as a blurb, but "accomplished", and "one of the few memorable pieces", coming from Louise Bogan? That'll do just fine. ( Rolfe Humphries, of course, was later shamefully abused by cronies Reed and Elizabeth Bishop.)

You know those funny little excerpts from small town newspapers that the New Yorker uses as filler at the end of columns? Like " Constabulary Notes from All Over"? The one following Reed's blurb reads like a parody of "Naming of Parts": 'That greenish tinge on October oranges is a botanical peculiarity. It needn't bother you. These oranges are at their sweetest for they have been ripening on the trees since last May. The color does not mean that they are at their sweetest for they have been ripening on the the trees since last May.— Richmond Times-Dispatch.'

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

On the evening of December 24, 1944, the BBC Home Service broadcast an anthology of poetry called a "Poet's Christmas," with readings of new work by Laurie Lee, C. Day-Lewis, and Henry Reed. Reed's selection, "The Return," is a an allegory of remembrance and the Second Coming:

Remember on Christmas Eve, as you stand in the doorway there

And regard us as strangers, the forgotten love we bear,

And shall bear it always over the frozen snow

When the door is shut again, and once again we go.

The souls of the forgotten, for whom there is no repose

When the music begins again, and again the doors close,

For whom a thought of yours would come the length

Of a whole dark hemisphere to give us strength. The "Poet's Christmas" was printed in The Listener on December 28, 1944 (.pdf). "The Return" was not entirely well-received by later critics, including G.D. Klingopulos, who called it 'facile and unfocussed' ( Scrutiny, Summer 1946), and William Elton, who described it as a 'hurdy-gurdy of sentiment' ( Poetry, June 1948). The Christmas Eve broadcast, however, drew the attention of none other than the novelist E.M. Forster, who composed a letter to Reed that very night in order to commend the poem. Two copies of Forster's letter exist: one in Forster's papers at King's College, Cambridge; the other with Reed's papers at the University of Birmingham. The letter is noted in Birmingham's description of the Papers of Henry Reed (Archives Hub):

Unfortunately, Reed did not keep the correspondence he received; although, interestingly, the collection does contain a photocopy of a letter written to Reed by E. M. Forster and praising Reed's poem The Return which was broadcast on BBC radio on Christmas Eve 1944. To have kept the letter Reed must have highly valued Forster's praise.

In the Collected Poems of Henry Reed, Jon Stallworthy provides the following annotation for "The Return," which quotes from Forster's letter:

E.M. Forster, hearing this Christmas Eve poem on the BBC Home Service on 24 December 1944, wrote to the author the same evening of the poem's connection with 'the idea that the only reality in human civilization is the unbroken sequence of people caring for one another: an idea, Forster said, which 'cannot be prettified into reciprocity or faithfulness, nor is there any such prettification in your poem'. A photocopy of Forster's holograph letter was preserved among HR's papers. (p. 157)

I had long thought that this was the first (and only) notice Forster had taken of Reed, until the recent publication of a collection Forster's radio scripts, The BBC Talks of E.M. Forster, 1929-1960: A Selected Edition (Mary Lago, Linda K. Hughes, and Elizabeth MacLeod Walls, eds., University of Missouri Press, 2008).

Between 1928 and 1963, E.M. Forster gave 145 talks for BBC radio, on literary topics ranging from Tolstoy's War and Peace, to contemporary Indian novelists writing in English. No fewer than 77 of Forster's talks were broadcast in India on the BBC's Eastern Transmission service. Forster, in fact, preferred the Overseas Services, as his talks were less subject to censorship (though still tightly controlled), and during the Second World War many of his India broadcasts were repeated in Africa, North America, and the Pacific (see B.J. Kirkpatrick's bibliography, "E.M. Forster's Broadcast Talks," Twentieth Century Literature 31, nos. 2-3, [Summer/Autumn 1985]: 329-341).

The BBC Talks reproduces the script of a wireless broadcast Forster gave as part of his monthly series "Some Books," in which he reviewed new books which would be of interest to English-speakers in India. Delivered on April 1, 1942, this particular review deviated from Forster's regular preference for prose, and was devoted to recent poetry. He recommends several new anthologies: The Little Book of Modern Verse (Anne Ridler, ed., Faber and Faber, 1941); Modern Verse, 1900-1940 (Phyllis Jones, ed., Oxford University Press, 1941); The Best Poems of 1941 (Thomas Moult, ed., Johnathan Cape, 1942); and Poems from the Forces (Keidrych Rhys, ed., Routledge, 1941).

Additionally, Forster suggests, '[I]f you take in the BBC periodical "The Listener," be sure you read the poems which appear in its pages: they are usually poems by the youngest generation, and I shall quote from one of them — Henry Reed's "Map of Verona" in a moment' (p. 179). Forster reads from two poems: George Barker's "To Robert Owen" (1939), and then from "A Map of Verona," which first appeared in The Listener on March 12, 1942 (.pdf):

It is a subtle haunting dream which has nothing to do with the war or with any practible peace. It plays with the idea of a map of an unvisited city, which we brood over, and upon which our imagination feeds...[.]

He has visited Naples once, after similar brooding, and knows that a map of a city cannot reveal a city, but his thoughts are of Verona now, and all his talk envisages her, and leads towards her...[.]

The Verona of this poem is not an enemy town, in Mussolini's possession, but a city of the heart, a possession of the imagination. The poem is personal, and since poetry, whether written by the old or the young, should be an individual expression, I am glad to conclude with it. (pp. 181-182)

There is an unfortunate but all-too-familiar postscript to this story. The notes for the April, 1942, "Some Books" broadcast indicate that the original typescript had the poem's author written as "Henry Green", and while Forster's BBC typist was known for making mistakes based on his handwriting, and Forster frequently improvised from his finished scripts, it seems unlikely the error was noticed before being aired. Forster even makes a point in his introduction that "Henry Green" is not to be confused with the critic, Herbert Read! Despite the misattribution, Forster's selection of Reed's poem is an estimable endorsement.

The BBC Talks of E.M. Forster was reviewed in The New York Review of Books, on August 14, 2008.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

Well, Hardy boys and girls, as with most things in life, the solution to yesterday's mystery would have been easily reached, had I simply paid better attention in math class. Or trusted in the radio times tables published in The Times.

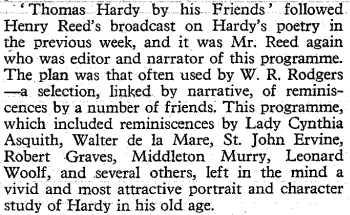

There is no great mystery: Henry Reed's radio tribute to Thomas Hardy was broadcast as advertised, on Sunday, February 20th, 1955, on the BBC Home Service, at 10:05 pm. Gibson's book had the date wrong, and I had mistakenly read "10.5" as 10:50, not 10:05. The Times, in their grand crusade for brevity and clarity, simply outsmarted me (not difficult to do, apparently). The program ran 47 minutes, until 10:52 pm. Here is the mention from The Listener's " Spoken Word" (.pdf) column for March 3rd, by Martin Armstrong:

(p. 399)

The clue to figuring this all out lies in that the seemingly ambiguous time references in The Listener. They're not ambiguous; they're rock solid. This Listener came out on Thursday, March 3rd, but covered broadcasting from Sunday, February 20th to Saturday, February 26th. Reed's 'broadcast on Hardy's poetry' falls in 'the previous week', even though it was broadcast only one day before "Thomas Hardy: a tribute from his friends."

Here is Armstrong's review of " The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: a study by Henry Reed," (.pdf) from The Listener of February 24th, 1955:

Thomas Hardy was a great English poet, but he wrote poetry as well as prose, or rather prose as well as poetry. On the previous evening Henry Reed gave an hour's discourse, with copious illustrations read by Mary O'Farrell, Michael Hordern and James McKechnie, on 'The Poetry of Thomas Hardy'. Listening to Mr. Reed I sometimes feel that I am back in the old classroom under the eye of one of the sterner and more intelligent of my schoolmasters and that if I were to venture a giggle or an independent view I would receive a disapproving glance. Nevertheless I enjoy myself and am the better for my lesson. Mr. Reed presented Hardy's poems in the light of his history, and this approach considerably enhanced one's appreciation of them. He suggested that a new edition of the poems is needed in which they run parallel with the biography—an admirable notion, it seems to me, but one that would involve a herculean job for its editor. The poems were excellently read by all three readers. Mary O'Farrell proved, if proof were necessary, that she is one of the two best women readers of poetry on the B.B.C. (p. 355)

Reed once had hopes of writing a biography of Hardy, and worked on this book on and off from the mid-1930s until the 1950s, when he finally gave in and gave up. These two, short broadcasts were the only tangible result of his 20 years of devotion and labor, his life's work. I sometimes also feel I am under the stern and disapproving eye of Mr. Reed, though sometimes, when I solve some particularly confounding problem, I feel him give me a wink.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

I'm sitting on a million-dollar idea. It's going to be the next Harry Potter, let me tell you. It's a Hardy Boys book, except instead of featuring boring old Frank and Joe, it chronicles the adventures of Thomas Hardy and his younger brother Henry: Tom and Hal Hardy, teenage sleuths in Victorian Dorset. Or maybe their adventures take place just before the publication of Tess of the d'Urbervilles. That would be contemporary to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and then Henry could play Dr. Watson to Thomas' Holmes, I can't decide. The Mystery of the Madding Crowd. The Clue Under the Greenwood Tree. A million bucks, I'm telling you.

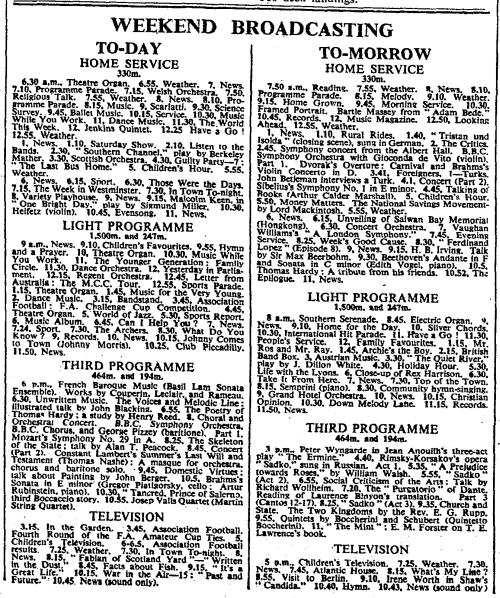

Maybe the Hardy boys could puzzle out this riddle: The Secret of the Two Radio Shows. In his chapter in British Radio Drama (John Drakakis, ed., 1981), " The Radio Plays of Henry Reed," Roger Savage mentions that in the 1950s, Reed presented "an anthology of recorded memories for the BBC called Thomas Hardy: A Radio Portrait by His Friends, observing that it is 'characteristic of a great deal of utterance on Hardy' that 'people prefer... to talk at length about themselves'" (p. 180). The Times' broadcast schedule for February 19th, 1955, lists two programs on Hardy that weekend (click for full size):

Under "To-day" (February 19, 1955), for the Third Programme: " 6.55, The Poetry of Thomas Hardy: a study by Henry Reed." Then, for "To-morrow" (February 20), there is listed on the Home Service: " 10.5, Thomas Hardy: A tribute from his friends." Which is the portrait mentioned by Savage? Either? Neither? The show following begins at 10.52, making the tribute only two minutes long. That can't be it.

Another clue comes from Michael Millgate, who sings Reed's praises in "The Hunter-Gatherers: Some Early Hardy Scholars and Collectors" ( Thomas Hardy: Texts and Contexts, Phillip Mallett, ed., 2002). Millgate refers to "a remarkable broadcast of 1955, made while [Reed] was working for the BBC, into which he incorporated the spoken reminiscences of Gertrude Bugler, Dorothy Allhusen, Robert Graves, May O'Rourke, Walter de la Mare, and several others who had known Hardy in his lifetime..." (p. 193). Surely Savage and Millgate are talking about the same program?

(Incidentally, I was set off on this mad quest by this audio recording of Walter de la Mare talking about meeting Thomas Hardy [BBC4, RealPlayer required], from April, 1955.)

I popped into the library on the way home from work tonight, and looked up a book called Thomas Hardy: Interviews and Recollections (James Gibson, ed., 2002), which mentions a BBC broadcast of February 19th, 1955, this time referred to as " Hardy and His Friends." Four excerpts from this broadcast are included, from: St. John Ervine, the novelist and playwright; Major General Sir Harry Marriott Smith; Llewelyn Powys, the writer (a single quote); and from May O'Rourke, who was Hardy's secretary during the final years of his life. Millgate specifically mentions O'Rourke as participating in Reed's broadcast, so it would seem that the Times' "study" is the program in question, though Gibson gives no credit or notation. Perhaps the title has gotten confused and concatenated.

I'll have to pull the Listener volume for 1955, and see if anything was written about the Hardy programs. Somewhere around here, too, I think I have a printout of the seventy-odd Reed broadcasts which were listed in the BBC's Programme Catalogue (before it went dark). Stay tuned! More Hardy Boys adventures to follow.

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

Look what turned up in the New York Public Library's Berg Collection of W.H. Auden material: Henry Reed's personal copy of Auden's Poems (1933). That's the second edition of Auden's first published poems from 1930, submitted to T.S. Eliot while he was at Faber and Faber.

The library catalog record states the copy 'contains ownership signature, " Henry Reed, 1943" on free endpaper'. That would mean this was a book Reed had with him during the war years, while he was stationed at Bletchley Park ( previously). No word on whether there's any marginalia, however.

The book was a gift given to the NYPL in June, 2007, from Eric H. Robinson. Could that be the Eric Robinson, historian and literary scholar, long claimant to the copyright ( Guardian) of the poems of John Clare (1793-1864)?

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

Happy Labor Day, comrades! I am enjoying a much-needed day off, despite the university being in full session, as classes began only last week. I worked twelve days in a row (plus a Pleasant Valley Sunday), and today I get to celebrate the fruits of that labor. I've been trying to get caught up on items which I copied or collected over the summer: tidbits, hors d'oeuvres, and appetizers, mostly; mentions, blurbs, and anthologies.

Two items come from the serial British Book News, a monthly collection of reviews of new books, put out by the British Council between 1941 and 1993 as a purchasing guide for schools and libraries.

The earliest entry for Henry Reed appears to be from July, 1946 (.pdf); a recommendation for Reed's poetry collection, A Map of Verona:

a map of verona. Henry Reed. Cape, 3s. 6d. lC8. 60 pages.

The first book of a distinguished poet and critic. Stylistically, Mr. Reed is considerably influenced by the later manner of T.S. Eliot. In the title poem he muses over a map and its literary and historical associations; in 'Tintagel' he evokes memories of Tristram and Iseult in the ruins of the castle; the more Tennysonian 'Philoctetes' and 'Chrysothemis' take the reader back to the ancient Greek world. There is also an ironical section, 'Lessons of the War'. (p. 276-277)

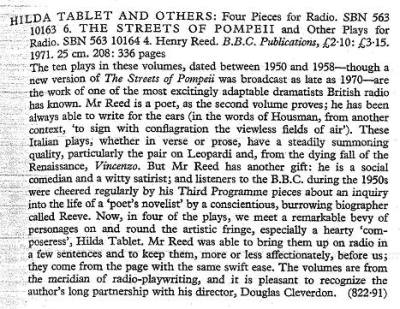

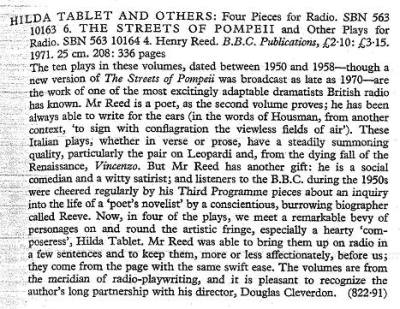

Later (much later), in the British Book News for February, 1972 (.pdf), we find an announcement for the publication of Reed's twin collections of BBC radio plays, Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio, and The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971):

(p. 153)

The Housman quote, while a lovely sentiment and excellent metaphor for radio, is gotten slightly wrong. It should be 'They sign with conflagration / The empty moors of air' (Google Book Search). (I'm not sure where "viewless fields of air" is lifted from. The earliest I can find is in The Memoirs of Carwin the Biloquist, serialized by Charles Brockden Brown between 1803 and 1805.)

Reed also appears in British Book News for his pamphlet of criticism written for the British Council, The Novel Since 1939 (1946).

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|

I'm sitting on a million-dollar idea. It's going to be the next Harry Potter, let me tell you. It's a Hardy Boys book, except instead of featuring boring old Frank and Joe, it chronicles the adventures of Thomas Hardy and his younger brother Henry: Tom and Hal Hardy, teenage sleuths in Victorian Dorset. Or maybe their adventures take place just before the publication of Tess of the d'Urbervilles. That would be contemporary to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and then Henry could play Dr. Watson to Thomas' Holmes, I can't decide. The Mystery of the Madding Crowd. The Clue Under the Greenwood Tree. A million bucks, I'm telling you.

I'm sitting on a million-dollar idea. It's going to be the next Harry Potter, let me tell you. It's a Hardy Boys book, except instead of featuring boring old Frank and Joe, it chronicles the adventures of Thomas Hardy and his younger brother Henry: Tom and Hal Hardy, teenage sleuths in Victorian Dorset. Or maybe their adventures take place just before the publication of Tess of the d'Urbervilles. That would be contemporary to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and then Henry could play Dr. Watson to Thomas' Holmes, I can't decide. The Mystery of the Madding Crowd. The Clue Under the Greenwood Tree. A million bucks, I'm telling you.