|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

Posts from November 2008

|

|

|

27.4.2024

|

Last week I was wondering about a perplexing snippet in Google Books, which implied that Reed had contributed to some unknown anthology, or collaborated on a larger work. I had a bit of a brainwave regarding keywords the next day, and managed to reverse engineer my way to the missing text (the secret phrase was "edited by"). The review in the Bookseller reads:

The Concise Enclyclopædia of Modern World Literature (50s.), edited by Geoffrey Grigson, which includes more than 300 articles on individual authors, and—to place them in their wider setting—articles describing the development of the major national literatures and characteristic literary forms of our time...[.]

The contributors... were asked 'to write about what they had enjoyed, communicating their enjoyment without escaping into superlatives'. There is a complete author/title index, and general bibliographies. There are 16 pages of colour plates, 160 in half-tone.

The London edition being prohibitively distant, I settled for a copy of the American edition of Grigson's Encyclopedia (New York: Hawthorn, 1963), just a short drive away, at a local public library:

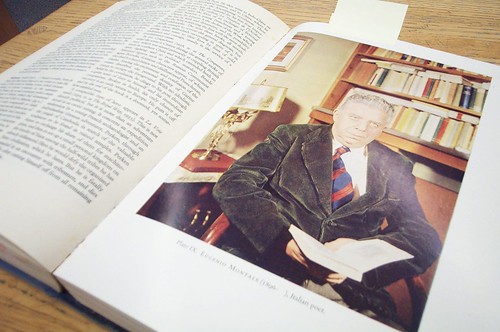

It's a beautiful book. Or, at least, it was beautiful in 1963. The reference copy I looked at had been ridden hard: the binding was torn and held together with book tape; the pages brittle and split on some edges. But the endsheets were still bright and colorful, and the entries lavishly illustrated (for an encyclopedia) with photographs, some of which I had never seen, including a picture of Louis MacNeice attending Dylan Thomas' funeral. Some thoughtful cataloger had even pasted the original front and back flaps of the missing dust jacket inside the front cover.

In his editor's Introduction, Grigson explains his instructions to the contributors:

Some writers — or some individual books — need rescuing from what is almost or entirely oblivion. Some have escaped attention because they are not easy to categorize.

Bearing this in mind that 'literature' is not really so common, in spite of publisher's advertisements, contributors to this volume were asked to write about what they enjoyed, they were asked to communicate, in a level way, their enjoyment; and to avoid, in doing so, both superlatives and the various ways of evading literature. One way of our time is historical, so they were asked not to indulge in chatter about trends, influences, schools, traditions. They were asked for sensible dogmatism — at any rate, for the unequivocal statement, and (where space allowed) for quotation — i.e., some part of the substance of what they were writing about. Another way of evasion is biographical. They were asked to concentrate on the books of each author, not on his life (though a biographical fact may be relevant, Yeats, for example dreaming of Bernard Shaw as a sewing machine which smiled and smiled). Even then, contributors were asked to concentrate on the books which mattered, instead of giving the neutral itemized survey which you might expect from a conventional encyclopedia. (p. 11)

(Yeats apparently had some difficulty digesting Shaw's Arms and the Man [1894]: 'Presently I had a nightmare that I was haunted by a sewing-machine, that clicked and shone, but the incredible thing was that the machine smiled, smiled perpetually.')

Alas, although there is a full list of all the contributors at the front of the volume—and biographical notes on them at the back—the articles in the encyclopedia are not signed. So we must take Grigson's instructions to heart, and ask ourselves, "Whom did Henry Reed enjoy? Who was Reed uniquely suited to concentrate on and communicate about?"

I made copies of the most likely suspects: Ugo Betti, almost certainly; Thomas Hardy, unequivocally; Montale and Montherlant, possibly; Pirandello? Maybe.

Update: After looking at my scans (linked above), Ed (of I Witness) feels strongly that the Hardy article is not Reed's (and I must reluctantly agree). But Ed thinks that the Betti is a possibility, and Montale, likely. Thanks, Ed!

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

In early 1946, the critic and editor William George Bebbington wrote an article comparing the poetry of the First and Second World Wars: " Of the Moderns Without Contempt" ( Poetry Review 37, no. 1 [1946]: 17-28). From the Great War, Bebbington chooses as his examples Rupert Brooke's " The Soldier," and " Battery Moving Up to a New Position from Rest Camp: Dawn," by Robert Nichols. For World War II, the selected poems are " A Wartime Dawn," by David Gascoyne, and " Spring 1942," by Roy Fuller.

In his introductory paragraphs, Bebbington reveals his purpose as championing the arguments made by Henry Reed, whose articles on contemporary wartime poetry for the Listener in January of 1945 resulted in an explosion of vehement letters from readers, which dragged on into March of that year (see " Points from Letters" for the entire exchange). While he calls Reed a "protagonist," Bebbington does not explicitly name the Listener as the source of his inspiration, but trusts that Reed's articles and the ensuing correspondence were well-enough known to his audience:

Of the Moderns Without Contempt In a recently published correspondence the intelligibility and popularity of modern poetry have been vociferously discussed, and accusations of considerable ferocity have been made. For instance, phrases like "a great sham, a prodigious bubble and a naïve hoax" have been used. The particular writer who expressed this surprising mixture of denunciations spoke simply of "modern poetry," and so far as he is concerned, therefore, all modern poetry is a naïve hoax and every modern poet is a charlatan. It is indeed a sweeping statement, but, to make matters worse, no analysis of how modern poetry is a sham, a bubble and a hoax was offered: the statement stood alone in its thundering glibness. One remembers how Martyn Skinner described "much modern verse": "vomit, nonsense, or mere deep-sea ink."

If only this particular writer (or Martyn Skinner) were concerned, however, there would be no cause for any modern poet or any student of poetry to be alarmed. But he is not alone. Unfortunately, there are all too many like him to-day making similarly unsupported and vulgar attacks on modern poetry, and all too many idle readers prepared to enjoy the saucy manner in which their attacks are made, and to accept their crude statements as true.

As Henry Reed, a protagonist in the correspondence, observed, such attacks on contemporary poetry are not new: history shows that many an artist's work must wait, often until after his death, for a true public valuation of it. T. S. Eliot's and W. H. Auden's poetry, Louis MacNeice's and C. Day Lewis's, is not inevitably destined to be forgotten merely because it has some noisy enemies to-day; nor does the fact of its present mass unpopularity necessarily mean either that it is not poetry at all or that it will never become widely respected and influential.

But let us not ignore present facts. Our modern poets are not popular, any more than our modern musicians or painters; nor are they even politely spoken of by those who do not read them—and it is this latter fact which is both new and disturbing. The poet as a species has not often been an object of public esteem simply by virtue of being a poet, but at least he has not been abused and rejected as a madman, a hypocrite or a criminal. The public at large may for most of our history have regarded him as at best a harmless fellow, but still it has, almost instinctively, believed in his integrity and the integrity of those who have been so idle as to read his work. To-day, however, the term "modern poetry" has become synonymous in the public mind with such expressions as meaningless doggerel," "cut-up prose" and "prodigious bubble." The publisher's blurb is careful to assure us that Julian Symons commands our attention because he is "one of the least obscure of modern poets"; Adam Fox in English (Spring 1943), writes: "the moderns, of whom Mr. Eliot is the leader and main inspiration, are in process of being abandoned even by serious readers of poetry as too unintelligible and only faintly pleasurable"; and even so discreet a poet and critic as Edmund Blunden does not miss the opportunity to stoke up the fire on which the books of the Moderns must be burnt, when in Cricket Country he writes: "but the author had made his meaning sufficiently clear: I trust that this will not be too much against him at the present time." In short, to be a modern poet to-day is to be a literary pariah dog.

It cannot be denied that a considerable proportion of modern verse demands of its reader much concentration and re-reading, but no sincere student of the art of poetry would consider such a demand in itself unjust; far poetry is not merely entertainment or even a form of recreation, it is an art—and art is not always easy either to create or to appreciate. It cannot be denied also that much modern verse is obscure, but much great poetry of the past is obscure in the sense that its subject-matter is uncommon, its imagery intricate and its vocabulary subtle (the love-poetry of Donne, for example). It cannot be denied that some modern verse is meaningless to a sufficient number of its serious readers to render its publication futile. It cannot be denied that some modern verse is not poetry at all. But to say these things is different from saying that all modern verse is obscure or meaningless or not poetry at all. For it is not the function of the critic to make glib generalisations, but to separate, analytically, the good from the bad, the genuine poem from the false verse or the "cut-up prose."

In the correspondence already mentioned, which originated from two articles written by Henry Reed [Poetry in War-Time: "The Older Poets", and "The Younger Poets"] on the subject of contemporary wartime poetry, Alun Lewis and Sidney Keyes, Stephen Spender and David Gascoyne were forced out of the discussion in favour of Rupert Brooke. It was argued that his popularity during the last war and the fact that a few of his lines are often quoted prove that he was a true poet who poetically expressed the general emotion of his day, whereas the modern poets of to-day are unreadable by any but a select few, and even they are as likely as not only pretending to understand.W. G. Bebbington. [p. 17-18] In his conclusion, Bebbington seeks to broker a sort of peace between older war poetry, and the new poetry of man-at-war: 'So their poetry is different, belonging to an older order, expressed in an older idiom, quieter, less severe, less analytical, less subjective. They are our modern cavalier poets, still writing for a court which has by now been almost wholly destroyed. They may not wish to recognise the destruction, but it is real enough to other men who are already seeking to build a new and very different court.'

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

I've found a few tasty morsels on Google Book Search in two publications put out by the Booksellers Association of Great Britain and Ireland, The Publisher and The Bookseller ("The Organ of the Book Trade"). Both the Publisher, and later The Bookseller, listed entries for the week's literary programs on the BBC, so here we find, in this volume from 1947, listings for February 23 at 10:38 pm, "Time for Verse: Compiled by Henry Reed, the poet", and for June 17 at 6:55 pm, "Book Review: Henry Reed on Shelley and Cecil Day Lewis".

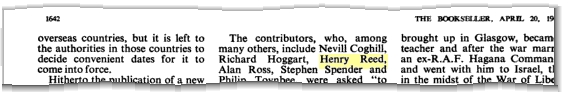

In the Bookseller for April 20, 1963, however, we discover something of a mystery: a reference to Reed and several other authors being asked to contribute something to something:

It says: 'The contributors, who, among many others, include Nevill Coghill, Richard Hogart, Henry Reed, Alan Ross, Stephen Spender, and Philip Toynbee, were asked "to..."' (p. 1642). But the limitations of snippet view do not allow us figure out exactly what these authors were contributing to, or even what they might have in common.

Nevill Coghill was a literary scholar known for his modern version of the Canterbury Tales, which was first produced for the BBC; Richard Hoggart was an academician, who was a witness at the Lady Chatterley censorship trial; Reed, Ross, and Spender were, of course, primarily known as poets; and Philip Toynbee was an experimental novelist.

What were these writers contributing to, and what was they asked to do? Trying to find a library in the States with a 1960s run of the Bookseller is an exercise in exasperation. University of Georgia libraries? At least I have the exact date and page number, which means I can try to get a photocopy through interlibrary loan.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

This review comes from the New Statesman and Nation for November 3, 1945 (p. 302-303). Reed devotes most of his time and effort to reviewing Bowen's The Demon Lover and Other Stories, which apparently he thoroughly enjoyed. Reed was friends with Bowen, and would later spend two weeks holiday with her at her ancestral home in Ireland in April, 1946 ( map).

New Fiction The Demon Lover. By Elizabeth Bowen Cape. 7s 6d

To the Boating. By Inez Holden Bodley Head. 7s 6d

First Impressions. By Isobel Strachey Cape. 7s 6d

It is not an accident that in her little book on the English novelists [English Novelists. London: William Collins, 1942] Miss Elizabeth Bowen should have written so well of Thomas Hardy and Henry James. Hardy, it will be remembered, thought poorly of The Reverberator, James not altogether well of Tess of the d'Urbervilles; and the two giants had little in common except their occasional dependence on a hard centre of melodrama—cruder, surprisingly enough, in James than in Hardy. Miss Bowen has something in common with both of them, though she manages to avoid their improbabilities, and she has enough of the true radiance of art to justify one's mentioning them. She shares Hardy's love of architectonics and of atmosphere: what Hardy will make of a woodland, heath, or starve-acre farm, she will make of a house or a summer night; and so far as persons go, I think the creator of Tess and Eustacia would have admired the drawing of Portia and Anna in Miss Bowen's The Death of the Heart. And she shares with Henry James a love of seeing how a story can be persuaded to present problems of artistry in the presentation of the "point of view"; and a curiosity (it is not the same as belief) about the supernatural and about the ambiguous territory between the supernatural and the natural. She has not James's sense of "the black and merciless things that are behind great possessions." Evil itself does not intrude on her world. It is not evil, but experience (they are not dissimilar, perhaps, but they are not the same) that corrodes the innocent people at the core of her books.

In her new collection of stories it is frequently obvious that she shares James's preoccupation with style; she has that kind of exact awareness of all she wishes to say, which makes her know precisely where a sentence needs to be a little distorted, or where an unusual word needs to be used. She has as well that gift which prose can share with poetry: the ability to concentrate the emotions of a scene, or a sequence of thoughts, or even a moral, into an unforgettable sentence or phrase with a beauty of expression extra to the sense:

The newly-arrived clock, chopping off each second to fall and perish, recalled how many seconds had gone to make up her years, how many of these had been either null or bitter, how many had been void before the void claimed them. Or again, about the present day:

He thought, with nothing left but our brute courage, we shall be nothing but brutes. Her short stories possess the qualities of her novels, but inevitably the atmosphere in her short stories is richer and more concentrated. The more elaborate of them suggest the climaxes of the elements of novels, but in a necessarily muted or diminished form; it is their atmosphere which moulds them, and which at times perhaps even brings them into existence. A perfect example of this is the first story in the book, "In the Square." Little happens in it, but enough strands are gathered together to give a sense of tension, climax and relief. And the relief is achieved mainly by atmospheric means. The story is about a few people living on in a partially bombed house in a ravaged London square. The principal feeling one has about them is their terrible independence of each other; all of them have mysterious, irregular relationships, unhappy and furtive. One has a feeling that what remains in the house, that reluctant proximity of the unconnected, is not what a house is meant to enclose. This is what war has done: to houses, to people. It is a true enough observation; but what startles one is the fact that one suddenly becomes aware that the early evening is spectacularly merging into late; the time of day is changing and a shift inthe emotions of all the characters is coinciding with this. A mere observation has become a story quivering with subtle, dramatic life.

The war, and the subtly degrading effect of the war, hold these stories together as a collection. They have a great variety and many attractions. One thinks particularly of their comedy and their dialogue; the story called "Careless Talk" is a brilliantly literal interpretation of that official phrase; "Mysterious Kôr" has a wonderful conversation draped round evocations from a poem by—Rider Haggard; the woman in "Ivy Gripped the Steps" is a strong enough figure for a novel. But it is probably those stories which involve the supernatural that are most striking. "The Demon Lover" itself, a ghost story of the traditional kind, is horrible enough, though not of Miss Bowen's best. In some of the others—"Pink May" and "The Inherited Clock," for example—the ghostliness is blown into existence by, or from, something real; and always, even when the boundary into the abnormal is passed, the normal still accompanies us.

The finest story in the book, and the most ambitious, is called "The Happy Autumn Fields." It begins in the past—perhaps seventy or eighty years ago. Various members of a large family are taking a late afternoon walk across the fields of their estate; at a moment of particularly painful emotion for one of the characters, Sarah, the story breaks off, and we are switched to the present: to a partly bombed house where a woman called Mary is waking from the scene we have just read about; it is not the first dream about the epoch she has had, though her real link with it is tenuous; nevertheless her dream has become obsessive, stronger and more attractive than her own life. The scene changes to the old family again, and we find that that afternoon in the fields Sarah had a black-out which has projected her for a moment into a world nameless and horrible—our own, we gather. The final scene is back in the bombed house, with Mary sorrowing over the irrecoverable day from the past which has blown into and out of her life:

I am left with a fragment torn out of a day, a day I don't even know where or when; and now how am I to help laying that like a pattern against the poor stuff of everything else?—Alternatively, I am a person drained by a dream. I cannot forget the climate of those hours. Or life at that pitch, eventful—not happy, no, but strung like a harp....' It is, like "The Turn of the Screw," a story which provokes interpretation and commentary; but since it is, in a serious sense, a discovery, there remains about it something of its own, at once inexplicable and profoundly satisfying. No living writer has, I think, produced a finer collection of stories than this.

Miss Inez Holden is well known for her skilful reporting of factory life. To the Boating is offered as a collection of short stories. But in most of them the bridge between reporting and art has not been crossed. in the first story, "Musical Chairman," there is an excellent account of a series of pathetic and amusing interviews between the Chairman of a Local Appeal Board and various people who are rebelling against the Essential Work Orders. But the fancy bits of stroy-telling in which Miss Holden has arbitrarily framed these scenes are so artificially stuck on that they have not been blown away in the proof-reading. It is a drab collection of oddments that Miss Holden has put together. And she shows, furthermore, a taste for drabness for its own sake. The book concludes with three fanciful little satires: presumably in order to deaden any excitement which these might arouse in the reader, Miss Holden has chosen to swathe them in the grey, vague mists of Basic English.

The habit, common enough in contemporary poets, of publishing work of an elementary or even infantile nature, is spreading to writers of fiction. Shown to one in manuscript, Miss Holden's stories and Mrs. Strachey's novel, First Impressions, might reveal promise; one would note passages of humour or observation. Why, then, does one pass over these when the books appear in print? Doubtless because the books challenge comparison with the early work of writers who seem to have tested themselves more rigorously and more critically before emerging into print. Amateurish is the deplorable word that one cannot avoid in mentioning Mrs. Strachey's novel. It is supposedly a satire on the leisured life of the Twenties. Possibly Mrs. Strachey has seen that life, but there is nothing in this rambling, unformed little book that could not have been got from many other social satire. Bad syntax and petty indecency are no substitute for the slickness of wit which some satirists achieve in their first books, and which it is hard for a satirist to do without. And the title of Mrs. Strachey's book goes no way to excuse its muddle.Henry Reed

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|