|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

Posts from March 2009

|

|

|

27.4.2024

|

At first, I thought this was going to be a discovery of epic proportions, like a photograph of some exotic species, long thought extinct, or the finding a previously unknown, unexpected comet. Of course, it turned out that I was simply taken in—made the butt of a fifty-year-old joke. What first appeared to be an entirely unheard-of, obscure book written by Henry Reed, turns out to be merely a spoof advertisement for a non-existent, unwritten book: Have with Thee to Corporation Street!, complete with manufactured blurbs from critical reviews:

The ad appears in a two-page spread of the December 25, 1954 issue of The New Statesman and Nation, part of section called "Christmas Diversions." This elaborate hoax by the editors is entitled "Publishers Anonymous," and it's laid out to appear exactly like publisher's advertisements for new books by frequent contributors, being released specially for the Christmas holiday. It only takes the reader a moment to realize they're being had, but that's all that would have been required to grab their attention and get them to read the entire feature. Follow the linked image to my Flickr set to see the whole thing, with close-ups, and explanatory notes for some of the more obscure inside jokes (I'm lucky if I understand half of them):

There's a running gag where all of Elizabeth Bowen's reviews for The Tatler proclaim the books are "Absolutely delightful!" (Bowen preferred not to give negative reviews, and only reviewed work that she enjoyed), except for a book on critical reviewing, which Bowen finds "Instructive!"

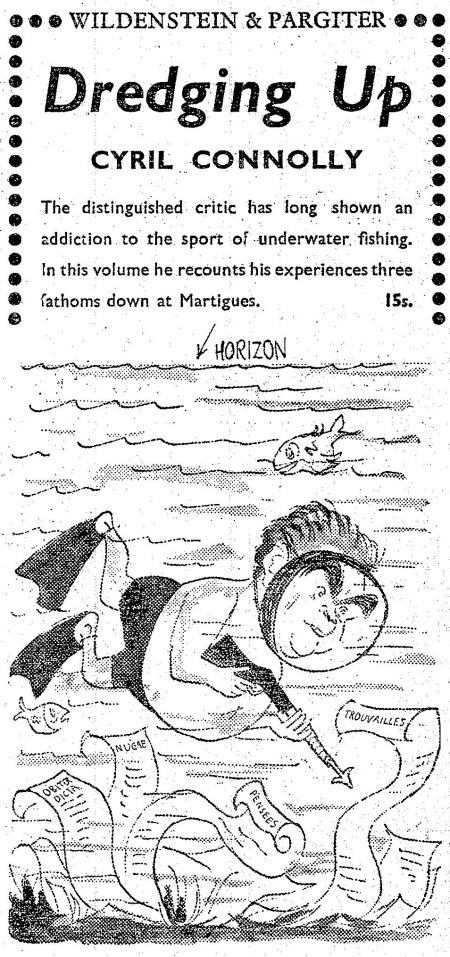

The invented publishing houses include: Bourne & Griffin, Fathom House, Hussif Publications, Ivy and Fitzroy, Parlour Press, and Wildenstein & Pargiter, with this jape about Cyril Connolly, editor of the journal Horizon:

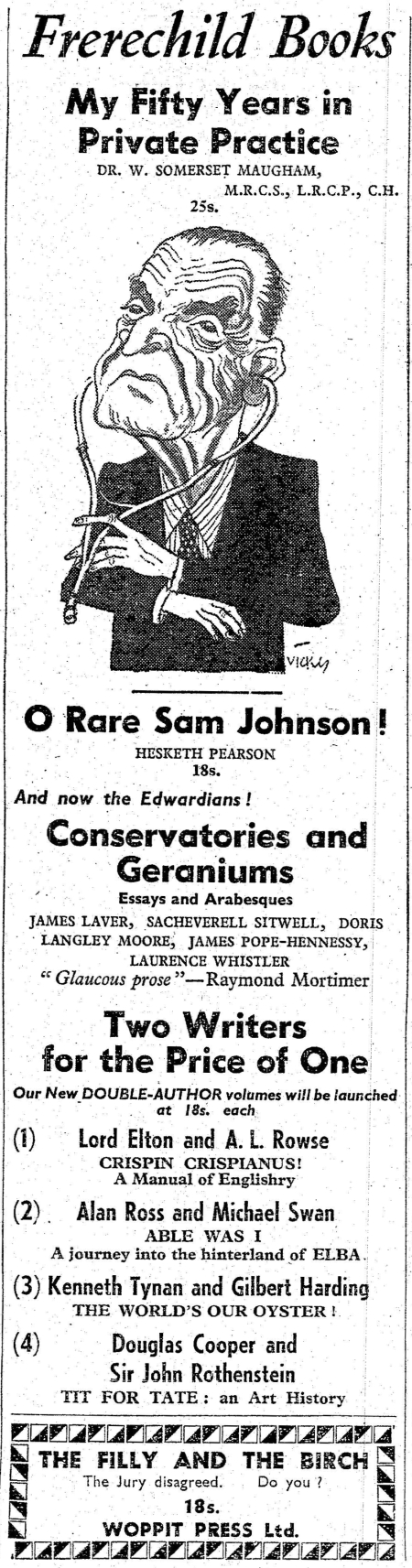

Then there's this delightful send-up of W. Somerset Maugham, who studied medicine before becoming a novelist, from "Frerechild Books":

The caricature was drawn by Victor "Vicky" Weisz, seen here at the British Cartoon Archive. Here's the entirety of the New Statesman's " Publishers Anonymous," scanned into a .pdf.

Even though it turned out to be all in jest, and I practically made a fool of myself, finding these pages is still significant. Reed was thought well enough of to be incorporated into the joke, which is certainly flattering. His inclusion places Reed among his friends and contemporaries, like John Betjeman, Elizabeth Bowen, Edward Sackville-West, and Angus Wilson. Reed's radio plays were apparently considered so popular they were replayed with almost ridiculous frequency. The comparison with Gogarty means that Reed was renowned as a wit of nearly Olympian proportions. And most importantly, the title of Reed's book secures him as a member of a group of writers and artists who frequently met at a pub off Corporation Street, Birmingham, in the 1930s: the Birmingham Group.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

Very well, then. Here are two hills. Here are two snippets from what I believe is the May, 1946 issue of Adam International Review—the title is an acronym for Art, Drama, Architecture, and Music—not the 1960s men's magazine of the same name (some images NSFW). Google Book Search doesn't particularly lend itself to any sort of exactness, but this would appear to be a book review penned by Alex Comfort, concerning Henry Reed's A Map of Verona, and perhaps Dylan Thomas's Deaths and Entrances, both published in 1946:

Alexander Comfort (1920-2000), M.B., Ph.D., was a poet, novelist, and physician, widely known for his writings on pacifism and gerontology. Perhaps to his dismay, however, Comfort will always be best remembered as the author of The Joy of Sex (1972).

One of the most prolific poets of the Forties, Comfort's early collections include: France and Other Poems (1942); A Wreath for the Living (1943); Elegies (1944); The Song of Lazarus (1945); and The Signal to Engage (1947). Here is just a small taste, from his "Sixth Elegy":

Love is not strong to fight with history

and those who love are sometimes buried together

sometimes apart, and move like shells

slowly into the heart of the cloudy hills... Comfort's personal papers are collected at University College London. The Adam Collection, the personal library of editor Miron Grindea, is housed at King's College London.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

Owing to some lovely winter weather this morning, I've got a brief reprieve from work: a half-day snow day. It seems unlikely that the journal volumes which I requested from library storage last week will show up today, so instead I'll post two items I've been sitting on for some time: illustrations for billings of Reed's radio plays from the Radio Times:

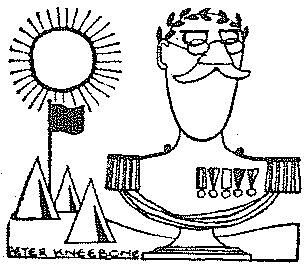

This illustration is by Peter Kneebone, and is from the Radio Times for May 1, 1959. It accompanied the billing for the sixth play in Reed's Hilda Tablet series: Not a Drum Was Heard: The War Memoirs of General Gland, first broadcast on the BBC Third Programme on May 6, 1959. The General looks distinguished, but he's quite mad.

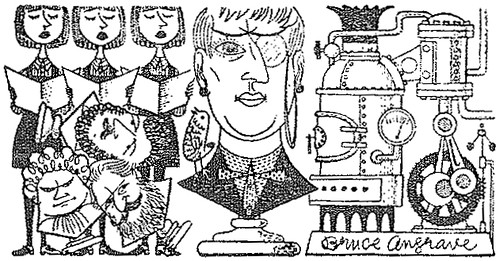

This drawing is by Bruce Angrave, from the Radio Times for October 23, 1959, illustrating the seventh and final play in Reed's sequence, Musique Discrète: A Request Programme of Music by Dame Hilda Tablet. The play premiered on October 27, 1959, with musique concrète renforcée provided by Donald Swann. Isn't Hilda's monocle a gas?

(I'm not embarrassed to admit that I could only recognize Beethoven's bust [bottom left] getting tumbled in Angrave's picture. Our friend the Webrarian came to my rescue: that's Wagner turned sideways, with Brahms just below.)

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

D.H. Lawrence died of tuberculosis in Vence, France, in 1930. Though he published two short novels before his death, Lady Chatterley's Lover was his last major work. Banned in the UK in 1928 for obscene language and explicit sexual content, Lawrence was forced to publish his book privately in Italy and France, in runs of less than 1,000 copies. Attempts at smuggling Lady Chatterley into the UK often resulted in the book being seized and burned, as seen in this 1932 customs ledger for the port of Dover.

In 1960, Penguin Books challenged a new obscenity law in Britain, finally publishing an unexpurgated edition. According to the Obscene Publications Act of 1959, a published work would not be considered obscene if it could be shown to have literary merit. On November 2, 1960, after a six-day trial ( photos), a jury declared that Lady Chatterley's Lover was not obscence, Penguin was acquitted, and the book released, selling out all 200,000 copies on the first day.

Henry Reed reviewed the newly-published edition for the Listener's Book Chronicle on November 24, 1960 (p. 948):

Lady Chatterley's Lover

By D.H. Lawrence. Penguin. 3s. 6d.

An atmosphere of hysterical over-excitement is not one in which a book may be most profitably read—still less reviewed. I wonder how many people have in recent weeks read the pages of Lady Chatterley's Lover consecutively, starting at page 5 and ending at page 317? We have all, like the jury at the Old Bailey, been conjured rather to dip into it here and there. This is not what Lawrence wanted at all. He wanted us to read his story, which he meant to be a good one. I have read it twice recently, and straight through. It seemed to me richer and more moving the second time than the first; but my total impression seemed on both occasions the same. Here was the mature work of a great artist, a novel which for all its occasional lightness was seriously intended to touch the heart, which had been composed with great thoroughness, and which was, like most of Lawrence's more extended works, grounded in moral protest. If I had to say what that protest consisted of, I would say that in simplest terms it is the championship of good sexual relations against bad ones: warm-hearted sexuality against cynical and cold-hearted self-indulgence and exploitation. Asked to say as briefly as possible what happens in the book, I would say that it charts the progress of its two chief characters from the desolation and forlornness in which we find them—and to which they have been reduced by present and past adversity—towards a state which holds out a promise of hard-won happiness. I cannot put it otherwise.

Others, apparently, can. We are told in a letter to The Listener of November 17 that 'as several critics have been quick to point out, Mellors already had a wife, and Lady Chatterley seems to have had no compunction about breaking up that marriage, so long as she satisfied her own lusts (she wasn't chaste even before she married Chatterley), while she apparently had no pity for her unfortunate crippled husband. And Lawrence shows no interest in what have been the fate of any illegitimate children that might have been born'. This is all wrong: in fact, in implication, and in deduction. Mellors has been long parted from his wife, beyond possibility of reconciliation; when Connie meets him he is living in contemptuous chastity, and there is no question of her breaking up a relationship. To speak of her as satisfying her own 'lusts' (surely the simple singular would be pejorative enough?) seems to me to suggest that she is merely using Mellors as an instrument, or that she is suffering from temporary or permanent nymphomania. Neither is the case. Of 'pity for her unfortunate crippled husband', she has an abundance; she also has love for him. It is he who has no pity or love for her. This is the point from which the entire plot develops. 'The fate of any illegitimate children that might have been born' is said to evoke no interest from Lawrence. But is not this the chief element in the whole last third of the book? As for Connie's 'unchastity' before marriage, this is presented by Lawrence (with mocking approval) as mechanically characteristic of her class and upbringing; and indeed the sexual side of her solitary little teen-age affair is undertaken rather as a boring fashionable duty than anything else. It is not the onset of a sexual mania.

But that people can, at either first or second hand, get such odd ideas about what characters in a book are like, and about what happens to them, is probably some sign of a book's disturbing realness. (Hardy's Tess, it may be recalled, could once be thought of as a 'little harlot'.) And Lady Chatterley's Lover is real because it is art. Lawrence's great gifts are all here: his powers of construction, of subtly unfolding a complex narrative, the sureness with which he can change his tone from sober to satirical, from bitter to pathetic, from humorous to grave; above all, his incomparable way of capturing the quickly changing shifts of feeling as the inner world of his characters is acted upon by the outer. The book is not without faults; in more extensive comments one would have to probe them. At this particular point in history one's concern must be to clear the reputation of the book from gross falsification; and to urge that all who would speak about it, either in praise or blame, should dutifully address themselves to the task of reading it, from (I repeat) page 5 to 317.Henry Reed

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|