[H]ow about a little balance? It might have been fun to have a poem by one of the younger, rising stars of British poetry - Luke Kennard, Daljit Nagra, Katy-Evans Bush, say - or mention of one of the many fine established women poets currently working in the UK. Instead, the page rather solemnly establishes an establishment feel. . . and a feel that experimental, different, edgy, or more radical poetic efforts will not be looked at.

|

Always to the SwiftTodd Swift of EYEWEAR reviews The Observer's new poetry section, which kicked off yesterday with 'three white, male poets - one dead, one middle-aged, and one slightly older than that': Henry Reed, John Burnside, and Hugo Williams.

Observer Book ReviewIn today's Observer, Adam Phillips reviews the new edition of Reed's Collected Poems (text only):

Reed has a plain eloquence for what goes wrong and for what then holds absurdity at bay. In 'The Door and the Window', a love poem about an absent lover, he writes of 'Waking to find the room not as I thought it was,/ But the window further away, and the door in another direction', as if the room (or the lover) in the world should match the room in the mind and that only in language can a door change direction or have any direction at all. Reed wants to show us, without melodrama, how disoriented we are by what language lets us do, what language lets us notice: 'It is not that courage has risen,' Antigone says in Reed's poem of that name, 'but that fear has failed for a moment.' The Collected Poems of Henry Reed is available for purchase through the Guardian Bookshop.

Poetry in War-Time: The Younger PoetsLast month, I promised I would return with the second of Henry Reed's essays for The Listener on English poetry during the Second World War. The first, "Poetry in War-Time: I—The Older Poets," concerned the work of Edwin Muir, Louis MacNeice, and C. Day-Lewis.

The second article, "Poetry in War-Time: II—The Younger Poets" (.pdf), appeared in The Listener on January 25, 1945. Reed opens with the argument that the younger poets writing during the war were most influenced by Dylan Thomas and W.H. Auden (some to their benefit, others to their detriment). There's a very funny bit wherein Reed lists the styles which were perfected by Auden and then imitated by young up-and-coming poets: the 'Famous Names poem'; the 'Bird's-Eye View of Europe poem'; the 'Evil Implicit in Our Age poem'; the 'Week-End Trip poem'; and the 'Post-Coital Insomnia poem'. We can forgive Reed for this statement if only because, while he was heavily influenced by Auden, he preferred to write like Eliot. The voices of many of these promising poets were 'drowned in the sea of stylisation' during the latter part of the war, but Reed heard at least four rising above the crashing surf, beginning with W.R. Rodgers: The first new poet successfully to emerge was the original and delightful W.R. Rodgers, whose volume Awake! created a sensation in 1941. He is particularly valuable for this brief survey, since he has given some account of his development. 'I was schooled', he says, 'in a backwater of literature out of sight of the running stream of contemporary verse. Some murmurs of course I heard, but I was singularly ignorant of its extent and character. It was in the late '30s that I came to contemporary poetry, and I no longer stood dumb in the tied shops of speech or felt stifled in the stale air of convention'. His remarkable poem 'Summer Holidays ' survives as one of the best long poems of the war. It is full of brilliance and gusto, wit and irony. Rodgers is a poet fond of alliteration and whimsical assonance: he loves words to set him problems, and he likes skirmishing with alliteration on awkward sounds like 'k' and 'j'; and he succeeds amazingly. Words tantalise him as they did Joyce. He is not a sentimental poet and this enables him to guy poets like Hopkins and Auden, who have loosened his tongue. He has quietened, and deepened, since the publication of his book; his poem 'Christ Walking on the Water' is wonderful in its imaginative and verbal resource (p. 100). Reed continues later with assessments of David Gascoyne, Vernon Watkins, and Alun Lewis: The three poets, however, who with Rodgers impress me more than others who have emerged since the war, are David Gascoyne, Vernon Watkins and Alun Lewis. Gascoyne's verse, of course, goes back some years before the war; his recent volume is called Poems 1937-42, and before 1937 he was known as a surrealist. Surrealist poetry is rarely very interesting, but it loosened Gascoyne's tongue for more deliberate work; and the associations with France which it probably brought him have provided him with an additional background. He is the least provincial of the younger English poets, and the one who seems best able to combine versatility and sincerity; poems as different from each other as his 'A Wartime Dawn' and 'Noctambules' are equally convincing. His series of poems called 'Miserere' is a fine achievement, deservedly well known. Whose is this horrifying face,Vernon Watkins I have difficulty in writing about. I find him at times very hard to understand, sometimes impossible; yet if a premature judgment may be allowed, I believe him to be the one poet of his generation who holds out unequivocal promise of greatness. I find myself not minding his obscurity; or as with Mr. Eliot, I am prepared to wait or to take on trust. His philosophy or metaphysics I suspect I should find antipathetic. Yet I never read him for long without knowing that here is a voice, at times one of the very loveliest: His music is rich, his cadences are subtle and he can prolong a line with great delicacy. Like Rodgers, Gascoyne and Mrs. Ridler he can write a long poem which sustains one's excitement to the end; his long 'Ballad of the Mari Lwyd' is a remarkable work. Dylan Thomas has left his mark on some of Watkins' poems, but he is more truly and deeply rooted in the past—in Rilke, Yeats and Blake particularly. His poetic allegiances are of the kind which exact, intellectually and technically, a good deal from a devotee. There the perfect pattern isThough Watkins seems to me the most brilliant of the newly-emerged poets, I feel a more intimate sympathy with Alun Lewis. We shall not see the fulfilment of Lewis's promise, and the developments hinted at in the later poems from India will remain incomplete. He was, on the surface, a simple poet; he painted the sad exile of the soldier with the utmost honesty, and his poetry is doubly moving because for all its firmness and objectivity, it is the poetry of one in whom war and banishment have broken the heart. This can go side by side with a devotion to fellowmen, and in Lewis it did; his verse and prose are the expression of it. The loss of him, as of Sidney Keyes, is greatly to be mourned. Keyes was a younger poet than Lewis, passionately dedicated to literature—his background was an extensive and an ideal one—and at his best, as in 'The Wilderness', he was a dazzlingly accomplished writer. It is idle to speculate on what their futures might have been; better to read their four small books of verse; best of all perhaps to read them quietly: I cannot but think that they would feel genuine horror at the fulsome praises and the emotional falsifications which will always coagulate round such tragedies as theirs. How they would hate this! For they were good poets, each sincerely allied to great traditions of literature through a healthy predecessor: Keyes through Yeats, Lewis through Edward Thomas. They therefore felt themselves to be part of literature itself and it is as that that they would prefer to be remembered and judged. There is much of their verse I could wish to quote: here I can merely transcribe a sentence from a letter of Lewis's, quoted in an anthology by Mr. Keidrych Rhys. It is worth remembering—indeed I think it is unforgettable—for it expresses the war-time predicament of Lewis and Keyes and of thousands of their fellow men and women: 'So much is dormant in me that I hardly know how I go quietly through my days as I do' (pp. 100-101). During the course of the article, Reed also makes honorable mention of the talents of Roy Fuller, Anne Ridler, F.T. Prince, Terence Tiller, Norman Nicholson, John Heath-Stubbs, and Laurie Lee. Reed's impartiality and objectiveness seems remarkable, considering these are the poets whom Reed will ultimately be compared with, and for the most part, found wanting. At the time of its writing, with his first volume of poems within view on the horizon, he certainly considered himself their peer. With the exception of his Lessons of the War, however, Reed became just another one of the voices lost at sea.

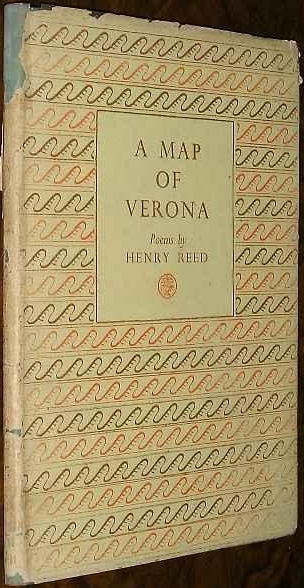

Window ShoppingThus far, I have not splurged and bought a copy of the original, 1946 UK edition of Reed's A Map of Verona: Poems. (I've been getting by with a complete xerox of a library copy.) Weekends, I like do a bit of window shopping, pretending I can afford to buy a signed, first edition (images link to AbeBooks.com):

Sitwell RespondsClarification continues to be supplied in tiny increments. I had a record for what I presumed was a letter from Edith Sitwell to Reed, written perhaps after his critique of her poetry in 1944's Penguin New Writing (v. 21). Her "Answer to Henry Reed" resides with the Dame Edith Sitwell Collection in the Harry Ransom Research Center at the University of Texas (previously).

This Catalogue of Sales (Google Book Search) for Sotheby & Co., from February - June, 1962, tells a different story: 252 SITWELL (EDITH) The Autograph Manuscript of her "Answer to Henry Reed," 13 pp., folio, signed below title, unbound. This interesting essay is a reply to a broadcast talk by Henry Reed in October 1946, in the Third programme series "The Poet and his Critic," devoted to Edith Sitwell's poetry. INCLUDED IN THE LOT are a typescript of Henry Reed's talk... (p. 54).So Sitwell's "Answer" is not so much a reply to Henry Reed, as it is her response. The poet D.S. Savage describes what the BBC's "The Poet and His Critic" program was attempting, while painting a dismal portrait of its failure. From "Letter from England," in the Spring, 1948 Hudson Review (p. 90): [The Third Programme's] musical record has been good, and its dramatic record not so bad, but on the literary side it has been deplorable. It has ventured into literary criticism. In a series entitled "The Poet and his Critic", a number of poets, some of them good ones, lent themselves to a painful exhibition in which the critic gave an appraisal of his pet poet on one day, the poet replied with a reading of his poems on the next, and there followed a coy little game of bat and ball on the third occasion between the two. But not all the poets were good ones, and the B.B.C. functionary in charge had scoured the alleys for the weirdest collection of so-called critics it would be possible to find within a hundred yards of Fleet Street. This seems to indicate that Reed hosted at least two Saturday evening programs on Edith Sitwell, if he wasn't involved in all three: the first on October 26th, the second on November 2nd, and the last, November 9th, 1946 (with Sitwell, herself?).

A Picture of a CatSpecial thanks to Alvy Ampersand, melissa may, Arturus, carsonb, routergirl, goodnewsfortheinsane, spinturtle, tehloki, maryh, paduasoy, jessamyn, cortex, pb, and of course, mathowie.

Generals, Giants, and ConjurersIn 1930, at the beginning of his professional career, Louis MacNeice took a post as an Assistant Lecturer in Greek at the University of Birmingham. Despite finding it difficult to adjust to life in Birmingham after coming up at Oxford, and discovering that work and married life were somewhat at odds with his creativity, during this time MacNeice managed to publish his first novel and his second collection of poetry.

According to Alec Reid in Time Was Away: The World of Louis MacNeice (Google Book Search), in 1934 MacNeice had written to his friend Anthony Blunt that he was working on no fewer than five projects for publication: '1 Poems; 2 Novel; 3 Play; 4 Latin Humour; 5 Analytic Autobiography' ("MacNeice in the Theatre," p. 73). It's the play that MacNeice was working on during this time that is of interest, here. Reid elaborates: According to William T. McKinnon, the play MacNeice hoped to see published in 1934-5 is 'presumably' Station Bell. It had given him [MacNeice] a great deal of trouble and was still unfinished by 8 June 1934. A note, probably in MacNeice's writing, attached to an imperfect copy of the play in the Library of the University of Texas at Austin reads 'completed c. 1935, performed by the Birmingham University Dramatic Society c. 1936.' Making all allowances for textual imperfections, Station Bell is a strange work. Written in an obviously 'Irish' idiom and set in Dublin in the near future, it centres on the seizure of political power by a female 'nationalist' dictator, Julia Brown, and on her unsatisfactory marriage to a tired but essentially humane and balanced academic. The other principal characters are a shabby military leader, a testy capitalist complete with saxophone, and a mad clergyman who is dispensing drink in a station bar in Act I and eloping for America with Julia in Act III. In between there is a very funny scene in which Julia and the General recruit a Propaganda Corps to represent the brave new Ireland. This includes a negro Celt who can dance an Irish jig, a mannequin complete with toy dog representing an ancient Irish wolf-hound, a conjurer, Séamus Stein, who materializes glasses of Guinness out of thin air, an epileptic drummer, and two Carnival giants. The Birmingham production, with a cast including Walter Allen, R.D. Smith, and Henry Reed, seems to have been a somewhat hasty affair (p. 74). (Presumably, Reid is referring to McKinnon's book, Apollo's Blended Dream: A Study of the Poetry of Louis MacNeice [OCLC WorldCat]. I'll have to check that out.) So, here we have four friends who would go on to become powerhouses of the 'thirties and 'forties, putting on a play together at university: MacNeice, Walter Allen, Reggie Smith, and Henry Reed. I can't help wondering, reading the description of the play (which was never published or performed professionally), what were their respective roles? Did Reed play the 'mad clergyman'? The conjurer? The corrupt general? The answer is probably buried in the annals of the University of Birmingham's student magazine, The Mermaid. Reid quotes a March, 1937 review of the university production: Mr. MacNeice is fairness itself. And since his frankness is both flattering and amusing, we had an evening of high jinks with the Dublin dictatress, giants and generals. The play has slapstick, satire and moments of real tension. I could not tell how much the failure to knit together as a whole was due to the hasty charade-like production and how much was due to the author's liking for action on various planes and his tendency to do too many things at once. In retrospect it is possible to appreciate the device reconciling the dictatress and her husband against the background of fumbling giants; in the theatre it can only be fidgety (p. 75). There is also a handwritten fragment of the Station Bell in MacNeice's papers at the Berg Collection of English and American Literature at the New York Public Library, and I see only one other reference to the play being produced: at Manchester University by the amateur "Unnamed Society" in 1937.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||