Long day today: having visited not one, but two, local Barnes & Noble bookstores. Sitting here now, idly typing, I can feel a thin film of dried sweat tightening over my entire body, from head to toes.

I was up early, again. I don't know why my circadian cuckoo clock won't allow me to get some decent rest, weekends. Up early, doused myself with a shower, and took a couple of Tylenol Sinus to fight off the effects of the previous evening's bottle of wine. That nice little Australian Shiraz, [yellow tail]: the one with the 'roo on the bottle. Seven bucks; can't be beat.

After my first, unproductive visit to the (first) bookstore, I got stuck in a rain-induced traffic jam long enough to outlast the morning's 'pirin. This necessitated visiting the second bookstore, for a fistful of coffee. At which point I bought the book that I had lingered over at the first Barnes & Noble. Ridiculous? I know.

I bought a copy of Code Breakers: The Inside Story of Bletchley Park. I had looked it over once or twice before, and though it doesn't mention Reed specifically, it does have some nice bits on the Italian Naval Section and Japanese decrypts. (Actually, what I've read so far is dry, unspecific, full of jargon, and about as interesting as a phonebook in a foreign country.) It has a few photographs, a good map of the Milton Keynes estate as it was in its heyday, and decent glossary of terms and abbreviations.

The only hard fact I have ever found about Henry Reed's time at Bletchley Park is a mention in an interview with I. Jack Good and Donald Michie, from IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 17, no. 1 (Spring 1995), in which Good mentions he and Reed were in the same rooming house: '[Reed] complained about the food. He said we ought to get together and complain to Mrs. Buck, who was the landlady, about the food.'

That's a fantastic bit of detail that is severely lacking in most scholarly accounts. Complain to Mrs. Buck about the food!

The problem is, the whole Bletchley Park operation was so tippy-Top Secret, many documents were destroyed after the war; and those that weren't have only recently been released, if at all. So most of what's known about the day-to-day operations come from oral histories taken from the people who worked there (mostly former Wrens, it seems).

The Bletchley Park website's online store offers several tantalizing histories and memoirs that I'd give my left rotor for a peek at their indices:

The Road to Station X, by Sarah Baring,

Bletchley Park People, by Marion Hill,

My Road to Bletchley Park, by Doreen Luke, and

We Kept the Secret, by Gwendoline Page.

Conspicuously absent is the intriguing title Enigma Variations: A Memoir of Love and War (sometimes subtitled Love, War and Bletchley Park).

I've often wondered—given the time he spent among ciphers, cryptographers, and linguists—if there might be some code hidden away in Reed's poetry, some crossword puzzle jumble left to be discovered, some veiled reference to his experiences there. Most of the poems in A Map of Verona were written while Reed was at Bletchley, as well as his script for his radio adaptation of Moby Dick, but his wartime work seemed to be something he prefered to remain separate, and eventually altogether left behind.

|

Bletchley Variations

Books, and Eminent DomainI have a 1964 Roget's Thesaurus which I treasure above most of my wordly possessions. If the apartment were on fire, I'd toss the cat out the screendoor, and stuff the Roget's down my pants before I started grabbing valuables. ("Is that a thesaurus in your pants, or are you just happy to see me?") When I was in high school, the book gravitated toward my room, ending up there whenever I was hammering out a term paper the night before it was due, and it was one of the "house books" I took with me when I moved out (along with the complete Encyclopaedia Britannica, and the Durant's Story of Civilization). I claimed ownership by right of eminent domain. Sometimes, the needs of the few outweigh the needs of the many. Besides, the bookplate in the front of the Roget's is in my father's name: after the divorce, I had every right to claim it in his name.

I've looked at the new-fangled thesauri they hawk in bookstores these days. None can compete with this 40-year-old concordance for thoroughness, ease of use, or vocabulary. At 552 pages, I don't even need to keep a dictionary handy: almost everything is right here, at my fingertips (unless Scrabble is being played, which requires the big Random House, unabridged). As a matter of fact, I use the Roget's as a sort of portable writing desk when I'm writing on the couch. But for looking up definitions of uncommon and infrequently-seen words, I'd have to go with the Oxford Dictionary of Difficult Words. But then, I'm a bit of a wordsnob (I still lose at Scrabble, though). As far as dictionaries are concerned, I have a simple rule of thumb I apply when shopping: the callipygous porphyry test. If a dictionary isn't large enough or complete enough to contain the words callypygous and porphyry, then it isn't worth its weight.

How Does a Poem Mean?As a follow-up to this post from May, here's the tale of the poet and translator John Ciardi from New Jersey's North South Brunswick Sentinel ("The only Sentinel bringing you both Brunswicks!"). Ciardi went from piloting B-29s in World War II to eating turkey with Isaac Asimov, translating Dante, and guesting on The Tonight Show. (Via Bookninja, via Bookslut.)

Terrarium BooksOnce upon a time, I had two fish: a pair of Bettas. Gandalf was a pale, blue-grey Betta who lived in a bowl in my office at work, and Saruman (it was the start of The Lord of the Rings movies. Hey, I didn't name them!), deep purple and crimson red, who had a magnificent, heated, ten-gallon tank all to himself on the bookcase at home. They were an impulse-purchase of a girlfriend and, along with the cat, rounded out our little menagerie.

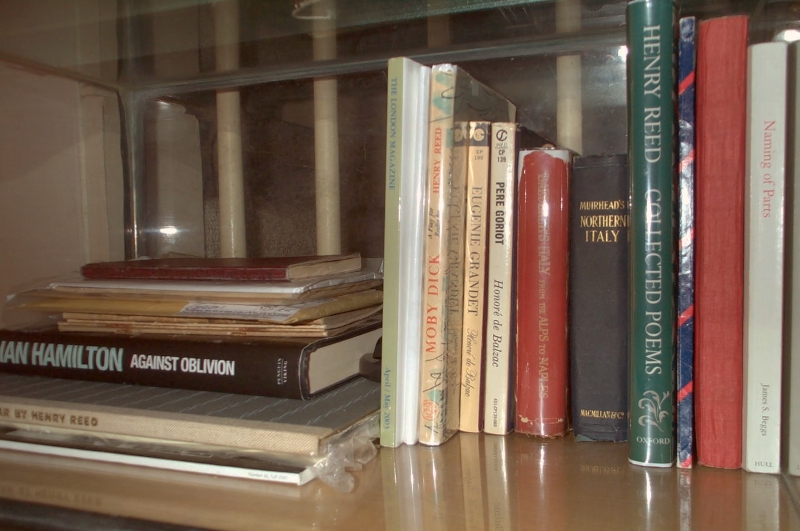

As pets go, fish are low, low maintenance; and Bettas are tough as nails, but they don't last forever. By the time the LOTR trilogy had played out in theatres, both Gandalf and Saruman had gone to that big brandy snifter in the sky. For the fourth time in the fifteen years that I've owned it (rescued from my half-parents' Wunderkammer garage), my aquarium lay sterile and empty. Somewhere in the apartment is a box containing tiny, ceramic Greek ruins: Corinthian pillars and capitals. When I described the sad sight of a barren, unused aquarium to a friend, lamenting the fact that I am, in fact, a dog person at heart, it was suggested that I use it instead to display books. Which are in no short supply around here. So I rounded up my scattered collection of hardcopy Henry Reed-related material, and created a sort of memorial, print terrarium: I own barely enough books on Reed to fill even half the aquarium. There's a couple of (relatively) recent journals: Cartographic Perspectives (Fall 2001), which contains an excellent article by Professor Adele Haft on Reed's use of maps and atlases in his poem "A Map of Verona," and The London Magazine (April/May 2003), with a reflective article by Anthony Howell on Reed's posthumously-published and lesser-known poetry. The rest are Reed's scant published works, and a few tangential and reference items. In my mania, I actually bought a couple of tourist guidebooks that Reed may have used during his several trips to Italy, containing the maps of streets through which his "thoughts have hovered and paced." What's significant is what's missing: two volumes of Reed's radio plays, The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (BBC, 1971), and Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (BBC, 1971). The university library here in town has copies, so they've been low on my list of books to fill out my collection. But now, taking a good look at my sad, half-empty aquarium, I think I'm ready to make room for them. Maybe I'll add a "wishlist" to the blog, or even incorporate as a nonprofit — the Friends of the Henry Reed Terrarium — and set up a PayPal account to accept donations.

tfeL ot thgiRI've been corresponding with a gentleman in Israel who has taken great care to translate Reed's poem "Judging Distances" into Hebrew. An audacious undertaking!

Having only a tenuous grasp of English myself, and no familiarity with the Semitic languages, I'm attempting to reverse-engineer the HTML generated from a Word document. Right-to-left reading is the least of my problems, and the commas are driving me crazy. Perhaps I may never get the knack. לא רק באיזה מרחק, הדרך בה אומרים את זה חשובה מאד. אולי לעולם לא תשלטו בשיטת אומדן מרחקים, אך לפחות תדעו איך לדווח צורות נוף: הגזרה המרכזית, מימין לקשת, ומה שהיה לנו ביום שלישי שעבר, ולפחות בסוף תדעו

The Diction of BrothelsI'm ashamed to admit it, but while my mother lay in hospital, I went to the local library. It sounds bad when you say it out loud. Someone asks, "Hey, what are you doing here?" and you have to reply, "Well, my mom's in the hospital, y'know, so I had time to photocopy some citations."

I was looking for a biography of Joe Randolph Ackerley, a former editor of the BBC's magazine The Listener, author and memoirist. I knew from a collection of his letters that Ackerley and Reed were friends, so I felt sure that A Life of J.R. Ackerley (Parker, 1989) would probably turn up something. Boy, did I ever hit paydirt (practically an anthill)! The Mary Jane and James L. Bowman Library is a branch of the Handley Regional Library system. It's a relatively new building, built on donated lakefront out in the boonies of Frederick County, Virginia. I'd never been, but from previous research I knew they had a copy of the biography. Since my mother was sleeping about 20 hours a day in the hospital, I pocketed all the loose change for the copiers that I could carry, and dropped by during a long lunch. It was well over 90° outside, and the library sat baking in its own parking lot, with nary a tree to shade a weary traveler (or a weary traveler's car, which currently is without a working air conditioner). In construction, the building reminded me strongly of an industrial chicken coop. Perhaps that was what the architects were going for. Of course the book was on the shelf: BIO ACKERLEY. (Ah! Dewey Decimal, how I miss thee!) I cracked it open to the index, first thing. Reed is only mentioned on about six pages, and I wasn't hopeful. But right off, the first page revealed a juicy tidbit: Ackerley was forced to fight to get Reed's poem "Sailor's Harbour" published, because it contained the word "brothels": We watch the sea daily, finish our daily tasksWhich is exactly the sort of playful, irreverent humor that makes Henry Reed terrific. Ackerley probably thought the "churches" line was great fun. Listener editor A.P. Ryan, however, arguing that this was not the sort of poetic language they were seeking to publish, wanted Reed to change "brothels" to "movies" (pp. 185-86). As far as I know, the poem never did appear in the pages of The Listener, but Reed seems to have befriended Ackerley because of the row. Later, Reed pops up again at Ackerley's farewell send-off from the magazine (which he refers to as his "funeral party"). Ackerley wrote in a letter: '...it was jollier than expected and went on until 8:30. The ebbing tide of distinguished guests had left behind them only a Corke and a Reed, and those I took off to dine. It was my last expenses sheet' (p. 352). The Corke can only be the poet Hilary Corke. It was October 29, 1959. One disturbing fact cropped up, related to Reed only tangentially: apparently at some point, efforts were made to purge the ranks of The Listener of homosexuals. Geoffrey Grigson is quoted: “Did I ever know a virtuous literary editor? Did I ever know one with an unfaltering conscience, a literary editor, a single literary editor, not given to compromise or betrayal? One. Joe Ackerley, of The Listener, whom some of his older colleagues in the BBC did their best now and again, to get rid of, in part, I imagine, because they knew him to be homosexual” (p. 182).The footnote mentions that Ackerley was once 'saved only by E.M. Forster's direct intervention with the Director-General of the Corporation.' Ackerley was certainly open about his sexuality in his memoirs, and his fiction also handles homosexual themes. I sometimes wonder about our friend Henry, and how overt or obvious he may have been, what troubles it may have caused him, and whom he trusted. I know of several stories in which people, strangers and acquaintances, didn't know he was gay. A fact which seemed to simply amaze him, as if it were the most obvious thing in the world.

Finicky ReaderI like to read with a rubber band and a pencil.

The rubber band is chiefly used as a bookmark, keeping me from having to re-read paragraphs or pages to figure out where I left off when I set it down. Starting a new novel, everything to the rear of my placeis rubber-banded, the bulk of the book, but once the center pages are crossed, the rubber band jumps to the front. But the rubber band also serves to keep a pencil secured inside the book, at least with paperbacks. I'll write notes in a paperback, but hardcovers are either to expensive to mar in that way, or just too cumbersome. In a paperback I'll underline and write notes in the margins, but I also write brief character outlines in the blank pages between the title page and first chapter, or on the inside-back cover. This is mainly because I have a lot of trouble with names — especially if they're foreign. French and Russian novels are the worst. The rubber band also helps me find my front- or end-notes in a hurry, when I forget who someone is (or what they did). This week, my mother had surgery to repair a herniated disc. The bad news is they managed to puncture her dura, the membrane around the spinal cord, and she lost a lot of spinal fluid. The good news is, with her extra recovery time, I managed to finish the Balzac. (And mom's okay, too.) After malingering in the first fifty or sixty pages of Père Goriot for weeks, I read the whole thing in a day and a half at the hospital. Next day, I slipped off to the local "boutique" bookstore, and got lollipopped into a $12 copy of Hammet's The Maltese Falcon. Really fantastic. All the best parts of the film came straight from Hammet's dialogue. I finished it in less than a day, and had venture out again into the blistering heat and humidity for more reading material, this time to the el-cheapo used bookstore. I picked up a slightly bent copy of Ethan Frome and, having heard only the most terrible things about the book, found myself a relatively sharp pencil, and prepared for the worst. (The previous owner had already penciled "Starkfield" in cursive across the top of page 15 for me, so I didn't have to.) There's a scene in Grosse Pointe Blank, where John Cusack runs into one of his former English teachers outside his old high school and asks if she's "still inflicting all that horrible Ethan Frome damage?" "Terrible book," he says, or somesuch. That was as much about Ethan Frome as I knew. Not a ringing endorsement, but not exactly the Times Literary Supplement, either. I had an epiphany this morning, pre-shower and still laying abed: Ethan Frome isn't so much a love story or morality tale, as it is a good horror story. Ethan Frome is Psycho, Blair Witch, and Deliverence. Ethan Frome is Fatal Attraction, in turn-of-the-century New England.

AntelopesI walked downtown yesterday, chiefly for exercise, but also to while away a few hours at the campus bookstore. It's finally warming up here, after a cool, wet spring. It was a pleasant walk, if a little on the hot side: there's honeysuckle in the woods along the road into town, and the Beds and Breakfasts have all kinds of fragrant, flowering shrubs which are coming into bloom. There are even some late flowers still punctuating the magnolias. (Or are they early?)

I'm trying to put detailed, relevant descriptions with each entry in the bibliography, making searches easier, and references to my hardcopy less necessary. At the bookstore, hogging wireless bandwidth and surping at a giant latte, I spotted a mention, in the Introduction to the Collected Poems, of Reed staying at the Antelope Hotel while he was researching his biography of Thomas Hardy (which he never finished), in 1945 or '46, after his release from the Service. Turns out, there are several Antelope Hotels in the UK. At first, I thought it was this Antelope Hotel, in Sherbourne, Dorset. Dorset is Hardy country. But the Introduction specifically mentions Dorchester, and both Hardy's cottage and his estate, Max Gate, are closer to that city. Perhaps this Antelope Hotel in Poole was the hotel mentioned? Last night, after dinner, I was trying to track down a photograph of the hotel, and discovered there once was, in fact, an Antelope Hotel in Dorchester proper. It's been turned into a shopping arcade. A mall, of all things: The Antelope Walk. A crying shame. In 1685, James Scott, the Duke of Monmouth and illegitimate son of Charles II, made a play to overthrow King James II. Following the defeat of the Duke's forces at the Battle of Sedgemoor, participants in the Monmouth Rebellion were rounded up and tried for treason. The "Bloody Assizes" (trials) were presided over by the Chief Justice of the King's Bench, better known as "Hanging Judge" Jeffreys, for his ruthlessness in currying favor from the Crown. The Bloody Assizes were held in the Oak Room of the Antelope Hotel, Dorchester, in September, 1685. Judge Jeffreys is said to have had a secret passage over the rooftops leading from his lodgings at 6 High Street West (now Judge Jeffreys Restaurant and Steak House. Not kidding.) to the Court. One hundred seventy-five convicted rebels were sentenced to transportation: sold into slavery in the West Indies. Still, this was probably preferable to the fate of the seventy-four men sentenced to death: hanged until dead, drawn and quartered, their heads displayed on pikes in throughout the West Country. Twenty-nine suspected rebels were pardoned. (Judge Jeffreys, by the way, died of kidney disease in the Tower of London, after James II fled England in 1688.) The old Oak Room is still there. It's a tearoom, now.

O Ken Russell, My Ken RussellOne of my favorite, obscure facts about Henry Reed is that he once worked with (or was supposed to work with) Ken Russell, the director.

Ken Russell, of Tommy fame. Ken Russell, director of Altered States. Billion Dollar Brain (with Michael Caine as Harry Palmer), and Bram Stoker's Lair of the White Worm. The Ken Russell. In his early days, Russell made short films and documentaries for British television. He made several experimental films with the BBC's Omnibus series — films which many consider to be of questionable taste, but which foreshadow some of the truly great movies mentioned above. This is where Reed comes into the picture. The award-winning playwright took at least one course with the BBC on writing for television (Reed is in the front row, second from the right) in 1952. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the days of radio drama and comedy were drawing to a close. The Third Programme, for which Reed wrote so many memorable plays, became Radio 3 in 1970. For some reason, Omnibus decided to pair the Sitwellian Reed with king-of-kitsch Russell for a television project on the composer Richard Strauss: Dance of the Seven Veils (1970). The director's final vision, however, couldn't have sat well with Reed: “The film depicts Strauss in a variety of grotesquely caricatured situations: attacked by nuns after adopting Nietzsche's philosophy, he fights duels with jealous husbands, literally batters his critics into submission with his music and glorifies the women in his life and fantasies.” —screenonline.org.ukApparently, the television audience was upset by the appearance of Hitler (among other things), and the complete film was only broadcast once. Later, when Richard Strauss' family withdrew permission for Russell to use the composer's music, Johann Strauss waltzes were substituted! (Which begs another question: which Johann Strauss?) Reed, however, still receives script and scenario credits on the film (for that matter, so does Richard Strauss). The draft of Reed's untitled teleplay remains in a notebook, collected among his personal papers. It would be his only venture into the realm of television.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||