|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

Posts from July 2008

|

|

|

27.4.2024

|

I returned recently to a book I first looked at back in October of 2006: London: City of Disappearances, edited by Iain Sinclair. A huge collection of stories about a London which no longer exists (or never was), it contains a small chapter by Richard Humphreys, " Death of a Cleaner," in which Humphreys attempts to discover something, anything, about his London house cleaner's enigmatic life, following the man's untimely death. 'Not everyone has a house cleaner who knew Dylan Thomas and Francis Bacon,' Humphreys begins, 'and who was born into an aristocratic family and went to Wellington College and Cambridge University. I had one, called Mr [Antony] Ashburner, and he disappeared from my life as suddenly as, fifty years before, he had disappeared from the life of his own family.'

I was surprised, on re-reading the chapter, on how many connections and confirmations to the story I had uncovered in the last two years, in the span of a couple of paragraphs:

I cannot follow them into their world of death,

Or their hunted world of life, though through the house,

Death and the hunted bird sing at every nightfall.henry reed, 'Chrysothemis'

According to his sister, [Ashburner] went up to Cambridge in 1939 to read law. If he did go to Cambridge it didn't suit him and he transferred to Birmingham, where he probably read English. There is a mysterious and evocative poem by the Birmingham poet Henry Reed, called 'Chrysothemis', 1 which gives an insight into Ashburner's life in the Second City. After his death, I found a galley proof of the poem in his untidy flat at the wrong end of Ladbroke Grove. There was a dedication, handwritten in ink: 'To Antony from Henry, December 1942'. The poem is darkly Eliotic and casts light on an important, if brief, relationship. It was published in John Lehmann's New Writing and Daylight that winter.

In a letter of 1965 — to Dorothy Baker, 2 a BBC Third Programme script-editor — Ashburner recalls this acquaintance during a brief spell when he was living in the basement flat of a house belonging to Professor Sargent Florence, the left-wing economist and sociologist. This was Highgrove, 3 a Birmingham house famous enough to be the subject of a short TV film by David Lodge. 4 Ashburner's flatmate was Dr Bobby Case, a pathologist at St Chad's Hospital. 'I wondered then,' he wrote to Baker, 'and I have sometimes wondered since, how it was that Bobby Case managed to get hold of so much offal for our dinners — in view of wartime shortages. . .'

Highgrove, a large house, now demolished, was the haunt of writers and radicals, such as Auden and Spender, as well as the novelist and Birmingham University lecturer Walter Allen 5 — whose name can be found in Ashburner's surviving address book. Highgrove was a Midlands bohemian hang-out unknown to most metropolitans. Perhaps, like Julian Maclaren-Ross, 6 another acquaintance, Ashburner was one of the misfits and deserters incarcerated in the psychiatric wing of Northfield military hospital [Wikipedia] in the Birmingham suburbs, one of W. R. Bion's [Wikipedia] patients (guinea pigs).

What else did he do in the war? Reed went on to work at Bletchley Park. My mother-in-law, who was in the same section, remembers him taking a female colleague out for lunch. Reed's Bletchley Park friend, Michael Ramsbotham, has no recollection whatever of Ashburner. Was he a conscientious objector? In my more fanciful moments I imagine he was a spy, although I'm not sure which side he would have been on. By the end of the war he was living in Fitzrovia and working at Foyles bookshop. He wasn't keen on Christina Foyle [Wikipedia], he told me.

1. ^ Reed's poem, "Chrysothemis," is a monologue spoken by the daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemestra, sister of Orestes and Electra. The poem is quoted at length in Gross's Sound and Form in Modern Poetry.

2. ^ Dorothy Baker shows up as part of Conroy Maddox's Birmingham entourage in Silvano Levy's The Scandalous Eye.

3. ^ Highfield Cottage (not "Highgrove", as Humphreys would have it), was the home of Louis MacNeice while he was a lecturer in Classics at the University of Birmingham in the 1930s. The house is one of the landmarks in this map of The Life and Times of Henry Reed.

4. ^ The television documentary in which Highfield figures prominently is As I Was Walking Down Bristol Street.

5. ^ Walter Allen was a schoolmate of Henry Reed's at King Edward VI Grammar School, Aston, and both men went on to the University of Birmingham.

6. ^ Henry Reed seemed to have a special hatred of Julian Maclaren-Ross, and wrote several negative reviews of his work for the New Statesman. In his book, Fear and Loathing in Fitzrovia (2003), Paul Willets quotes one review in particular, from March 2, 1946:

Like its predecessor, Bitten By the Tarantula attracted some scathing reviews. And, once more, the severest of his detractors was Henry Reed, whose hatred of Julian's work was fortified by a hatred of Julian himself. 'Mr Maclaren-Ross's book,' he wrote, 'is very well bound and generously, though not elegantly printed; but its last three pages increase their number of lines from thirty-four per page to forty-one, thereby giving a peculiar stretto effect to the narrative which is, in fact, its sole interest. [...] The point of Mr Maclaren Ross's novel is not obscure. It has none.' (p. 189)

In defense of his character, Maclaren-Ross had an ally at the BBC in producer Reggie Smith, also a Birmingham colleague of Reed's.

City of Disappearances is due out in paperback this fall.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

Wilfrid Mellers was a critic, composer, and in 1964, founder of the Department of Music at the University of York. Professor Mellers is world-renowned for his enthusiastic love of all music, but especially for his embrace of folk, jazz, and pop. During his lifetime he produced a flood of books, articles, and original compositions, and was a respected pioneer in the study and teaching of music.

During the 1930s and '40s, while he was a supervisor in English at Downing College, Cambridge, Mellers was writing literary and musical criticism, most notably for the journal Scrutiny ( Music & Vision article). One review he produced, notably for us, was for Henry Reed's debut collection of poems, A Map of Verona. The piece appears in the July, 1946 issue of the New English Review. Over the past weekend, I popped over to the James G. Leyburn Library at Washington & Lee University to have a peek:

I was surprised to find not simply the blurb I had expected, but a lengthy review in which Mellers perceives the influence of Eliot on Reed, and Auden's influence on Geoffrey Grigson. From " Some Recent Poetry" (.pdf), by W.H. Mellers:

It is this search for formalisation, whether in slight or more difficult work that I find impressive in Reed's poetry. It is true that so far there is a certain limitation of emotional range about his characteristic movement, that the short poems are the more successful, and that the longer free-verse monologues evoke a comparison with Mr. Eliot's mature economy in this manner which no contemporary verse could live up to (even such sober and dignified verse as the vision of the dancers in "The Place and the Person" appears almost garrulous in so far as it suggests a relation to the "Dantesque" passage in "Little Gidding"). But Mr. Reed is none the less a poet and not a verse-maker; one awaits his next volume with lively anticipation.

(Mellers was, apparently, a firm proponent of both italics and a liberal sprinkling of "quotation marks".)

Reed's 'next volume' never appeared, disappointingly (unless you count the five collected Lessons of the War, in 1970), but I have happily added Meller's review to the critical section of The Poetry of Henry Reed—the first major addition to the site in over a year—reviving hope that there are still forgotten book reviews out there, hiding in unvisited libraries, waiting to be rediscovered and reread.

Wilfrid Howard Mellers died on May 16, 2008 ( Times obituary), in Scrayingham, North Yorkshire, at the age of 94.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

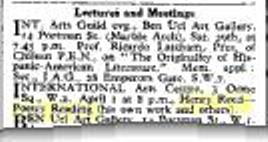

Here's a sliver of a New Statesman and Nation discovered in a Google Book search:

What's that? Can't quite make it out? Let's blow it up a bit, then:

It would appear to say, in the "Lectures and Meetings" column: 'INTERNATIONAL Arts Centre, 3 Orme Sq., W.2. April 1 at 8 pm., Henry Reed—Poetry Reading (his own work and others).'

I'll have to go flip through some old New Statesmans to confirm the year, but it looks like it's from 1947. ( Confirmed: this notice appeared on March 29, 1947.)

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

I'm thinking of adding a feature to the blog: "Reed Reviews." From time to time I'll reproduce a book review written by Henry Reed. I've collected a forest of Reed's criticism, and most of it is just sitting in my living room, of little use to anyone. And, since I've been lamenting of my meager bookshelf over on LibraryThing, I'll start adding those books which Reed reviewed to their own set.

I was surprised to find this review of V.S. Naipaul's Area of Darkness this past week. First of all, it's later than most of Reed's critical work, from 1964. Secondly, it's from The Spectator; the only piece which Reed wrote for them, as far as I know. I turned it up in a bibliography of Naipaul's work.

Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul (1932- ) is a native Trinidadian who has spent most of his life living in England. During the 1960s, he began visiting his ancestral country of India, and the resulting travelogue, An Area of Darkness, is considered a stark and unflinching look at the social problems afflicting India at that time. Here is Henry Reed's review of Area of Darkness, "Passage to India" Spectator, 2 October 1964, 452-53 (.pdf). V.S. Naipaul was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2001.

Passage to India An Area of Darkness. By V.S. Naipaul. (Deutsch, 25s.)

Mr. Naipaul does not mention the most interesting thing about his first, and possibly last, visit to India. It may, indeed, easily escape attention. I refer to the fact that his last novel, Mr. Stone and the Knights Companion, is dated 'Srinagar, 1962.' From this one gathers that in the middle of a sojourn in the country of his remoter origins, obsessed by a desolation and despair that will not everywhere command sympathy (though my own sympathy with Mr. Naipaul is, for what it is worth, complete), the author managed to clear for himself a small area in the all-pervading mess and confusion, and to impose thereon a precarious stability in which he could work. This he obtained by shouting, threats, and a bullying insistence that promises must be fulfilled. He had chosen to stay and work in a ramshackle houseboat-hotel on the shore of a Kashmir lake. Here, in exotic surroundings, wildly insecure in every personal contact, Mr. Naipaul seems to have written his story of the over-ordered, logical life of Mr. Stone, a middle-class Englishman, whose own order and certainty are beginning to disintegrate before the onset of age. There is something almost sublime in the thought of a writer, surrounded by one form of madness, sitting down and describing another: perhaps the aim, conscious or unconscious, was to avoid yet a third, himself.

This long middle section in Mr. Naipaul's book is beautifully done: the personnel at the hotel have much of the comic vividness and completeness of the characters in The Mystic Masseur. But there is no farcical exaggeration, and the passage is not detachable from the rest of the book. Almost certainly it is these pages, together with the grimly fantastic prelude at the customs house with which the book opens, that Mr. Naipaul's regular readers will find most to their liking. He is a genuine artist: he has acquired a surreptitious love for his subject before he can laugh at it.

Alas, he found very little to love in India, and therefore little to be comic about; and he is, I conjecture, too honest a man and too good an artist to try and manipulate what he hated into anything more than plain statement. The power of his book as a whole lies in something that is usually absent from accounts of India: an avoidance of rhetoric. Mr. Naipaul records, candidly and ruthlessly, what he hated there, and what it made him hate in himself—his reactions of near-hysteria, disgust and panic; and above all, perhaps, his guilt at an incapacity for charity, a guilt which his recognition of a genuine Indian sweetness of disposition and behavior could only agonisingly redouble.

How much he was prepared for such reactions it is impossible to say. In the event, he found India horrible in its present state; and he could see no apparent hope for its future. To him the whole place was desperate, flaccid, incoherent, muddled, discontinuous, and physically sickening. His pictures of India are too many and too complex for brief recapitulation; but it would be an affectation to avoid mentioning that the book reverts again and again to a fact he is bluntly explicit about: the bland Indian habit of public defecation. This simple fundamental Scheissmotiv is always booming up from Mr. Naipaul's orchestra. He seems to see it (and I recall similar feelings, more fastidiously expressed, in Forster's preface to Anand's Untouchable) as the basis of Indian life. But he is convinced that its importance and danger and nastiness cannot be impressed on a country whose main character-trait is a capacity for manic denial.

Mr. Naipaul's conclusion (a depressing comment, not an invitation) is that 'India, it seems, will never cease to require the arbitration of a conqueror.' This remark, in itself no more than a bitter parenthesis, will doubtless give great offense. It will doubtless be construed as an approval of whatever ideas China or Russia may entertain about India's future. It is, of course, nothing of the kind: any more than it implies approval of the British Raj, whose sole residual effect, according to Mr. Naipaul, is to have posthumously created, among wealthy business-class Indians, a grotesque charade-like life where everyone plays at being super-English, the men calling each other Andy and Bunny, the women anxiously clutching their copies of the Daily Mirror and Woman's Own.

Mr. Naipaul will be attacked for the things he says. He will no doubt be trounced, vindicated, and trounced again. Perhaps he will even be proved factually wrong. That would be good, and would matter. But at least he will have contributed with passion and sincerity to an important and sometime somnolent debate. That, too, matters. And to whom it may concern, this book also exposes that deep, reasonable, non-psychotic sadness from which comedy must find its way up and out: in this book we can glimpse a notable artist making (or having made for him) that harrowing choice between the sorry thing that can just be laughed at and those that can only be wept at.

henry reed You can read more of Henry Reed's book reviews by following the " Reviews" tag, below.

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

Julian Potter, writing of his father's days as a radio writer and producer, in Stephen Potter at the BBC: 'Features' in War and Peace (Orford, Suffolk: Orford Books, 2004), devotes a short sub-chapter to Henry Reed's 1947 adaptation of Melville's Moby Dick for the Third Programme. The Third was all of four months old when Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel aired in two parts on the evening of Sunday, January 26th, 1947, and the play helped substantiate the new programme's reputation in providing dramatic productions for discerning listeners.

Stephen Potter (Wikipedia) produced the radio version of Moby Dick, and his correspondence and diaries lend some idea of what an arduous task such an undertaking could be: a year in the making; acquiring a composer and getting the music just so; editing Reed's script; with delays owed to casting and illness—everything down to the wire until just before broadcast.

Julian Potter falls victim to one of the classic blunders, however: he gets Reed's name wrong. Throughout the book he mistakenly confuses Henry Reed with the author Henry Green. This is simply unconscionable, and can only be forgiven if one supposes the senior Potter referring to Reed by Christian name only in his interoffice memos and diary entries.

Here is the section from Potter at the BBC concerning the production of Moby Dick, with Reed's name properly amended (pp. 195-197):

Moby Dick

Stephen's longest single production was Moby Dick, a radio adaptation of Melville's novel by Henry [Reed]. It lasted two-and-a-quarter hours and was of a length that only listeners to the Third were expected to tolerate. [Reed] had written it while working during the war as a cryptographer at Bletchley. Presumably he had a broadcast in mind, but at the time he affected to despise radio. He was converted by The Dark Tower [by Louis MacNeice]. After hearing it, he wrote to MacNeice in January 1946, 'I have always thought your claim for radio's potentialities excessive; I now begin, reluctantly, to think you may be right.' Stephen had read [Reed's] adaptation and promoted it: at a lunch with [Sir George] Barnes on 31 January it was agreed that he should produce it and that it should be earmarked for an early broadcast on the Third. 'Will [Benjamin] Britten do the music?' wrote Stephen in July. As Melville's Billy Budd was later to be the subject of a Britten opera, his treatment of Moby Dick would have been of great interest; but in the event the music was written by Anthony Hopkins.

Hopkins later described his task, saying that as soon as Stephen Potter asked him to do it, he realized that it would require a full orchestra and that since so many players crammed into the studio along with the actors would be disruptive, the music would have to be pre-recorded. He had the knack of reading aloud the text while at the same time playing his music on the piano. This helped to get the length of each stretch right, but in case of overruns, he had for the first time used two gramophones. The music that accompanied the more meditative speeches was such that if the actor overran, the music too could continue, while the music for the next scene could start with the other gramophone whenever the moment came.

For Ahab, Stephen wanted Ralph Richardson, who just at the wrong moment went down with 'flu. Stephen managed to get the already scheduled programme postponed until January. He wrote to [Laurence] Gilliam: Only by postponing can we get Ralph Richardson for Ahab. He is far and away the best actor for the part: he has the exact right combination of earthiness, ordinariness and inspired fanaticism.... If he acted Ahab, it would make this production (provided I could play my part) one of the most successful and exciting programmes that the Third Programme and indeed the BBC has ever done. Thursday and Friday, 23 and 24 January 1947. Now I start to get going with Moby, in the biggest production I have ever had to do with. Difficulty No. 1 is New Statesman and News Chronicle. I have to go to NC in the morning. In the afternoon we do the music and I like the sound. But I have to prepare tomorrow's gigantic readthrough with large cast, many of which I do not know. First horror — Ralph has 'flu (again!) and threatening laryngitis and must spend tomorrow in bed.

After many more distractions, I really get going on preparing the script (87 pages) at eleven pm and have broken the back of it at 6 o'clock in the morning. This late night made me in what I felt to be tense and therefore bad form for the read-through at Langham [Broadcasting House]. The Friday read-through, scheduled for 10.30 am to 5 pm, took place without Richardson, although he was well enough to take part in the actual production. Because of its length, it was pre-recorded in four parts over four days of the following week and broadcast in two parts on the Friday. The cast also included Bernard Miles as Starbuck. In line with the Third's new policy, a recorded repeat was broadcast on 18 February; and in September, there was a new production of the whole thing. Substitutes had to be found for Bernard Miles and two other actors, but Richardson was again Ahab: Saturday and Sunday, 6 and 7 September. Two days full rehearsal of Moby so as to leave Monday, transmission day, clear. I have been dreading this; but in fact I have enjoyed it. Ralph is in superb form. He shows us a correction of a misprint: the sentence which spoke of 'our defective police force' should of course have read 'our detective police farce'. The gorgeous thing about these rehearsals is that Ralph, the monarch, treats me as if I was Prime Minister, and sends my stock up with all the other actors in consequence. The programme was repeated a number of times thereafter. [Reed], as has been noted, became a prolific and admired contributor to radio. Nearly all his subsequent programmes were produced by Douglas Cleverdon.

Oddly enough, I was unable to find a listing for the new production of Moby Dick in the Times' BBC broadcasting schedule for the week of September 8, 1947, but there is a copy of a script with that date among Douglas Cleverdon's papers at the University of Indiana's Lilly Library. (This may be a good time to point out that the BBC taking their Programme Catalogue offline is a serious impediment to research.)

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|