|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

Posts from April 2011

|

|

|

27.4.2024

|

Sometimes, the quest for Reed means discovering exactly where he wasn't on a given day.

In April of 1975, the World Centre for Shakespeare Studies, headed by Sam Wanamaker, presented the fourth annual Shakespeare Birthday Celebrations. Events that year included a two-month exhibition of "Shakespeare Round the Globe" at the Bear Gardens Museum (now Shakespeare's Globe), a gala concert of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra—featuring the Huddersfield Choral Society (conducted by John Pritchard), Ermano Mauro, Richard Briers, Judi Dench, Richard Johnson, Barbara Leigh-Hunt, Spike Milligan, Leo McKern, Richard Pasco, and John Stride—performing at Royal Festival Hall, and a concert of "Shakespeare jazz" at Southwark Cathedral (directed by Neil Ardley and coordinated by Ian Carr), with performances by Roy Babbington, Pete and Pepi Lemer, Henry Lowther, John Marshall, Dave Macrae, Paul Ruthorford, Alan Skidmore, Chris Spedding, Trevor Tomkins, Ray Warleigh, and others.

Concluding the festival was a poetry recital on the evening of April 26: "Poems for Shakespeare IV," also staged at Southwark Cathedral. Scheduled to read were Keith Bosley, Ernest Bryll, Sydney Carter, Veronica Forrest-Thomson, Erich Fried, Tony Harrison, John Heath-Stubbs, Jon Silkin, Ken Smith, Val Warner, Augustus Young, and Henry Reed, delivering poems commissioned specially for the event. Musical accompaniment was provided by Helen Sava and Michael Hunt.

Advertisement from The Spectator, April 26, 1975.

I was initially excited that Reed had made an appearance—possibly with a new poem—but I was skeptical. An anthology of pieces from the recital, Poems for Shakespeare 4 (Anthony Rudolf, ed. Globe Playhouse Trust, 1976), was released the following year, but Reed is not listed among the contributors. From British Book News:

This is the fourth collection of poems based, however intimately or remotely, on the experience of reading Shakespeare's plays; they were originally read as part of the Shakespeare birthday celebrations at Southwark Cathedral last year. Ten poets are each represented by a single poem, ranging from a vigorous, straightforward and pleasantly ironical ballad by Sidney Carter [sic] to a strange elliptical and disturbing meditation by the late Veronica Forrest-Thomson. My own favourites are 'Winter in Illyria' by John Heath-Stubbs and 'Winter Occasions' by Ken Smith. Anthony Rudolf's introduction is oddly aggressive except where it pays deserved tribute to Miss Forrest-Thomson.

Further research on the event turned up this excerpt from Augustus Young's memoir, Chronicling Myself, wherein he discusses "Veronica" (at the bottom of the page):

Her paradis artificiels were cut short two years later. At 'Poems for Shakespeare' in Southwark Cathedral I stood at the back, breathing the air coming up off the river. On the Tube home, Eddie Linden told Tony and myself that he saw Veronica in one of the cloisters, but she had disappeared before her turn came to deconstruct Shakespeare. That was the night of her suicide.

She lives on, on the tip of the tongue of the L-a-n-g-u-a-g-e poets.

Veronica Forrest-Thomson, an influential poet, is best known for her book of criticism, Poetic Artifice (Manchester University Press, 1978). Jacket Magazine had an issue devoted to Forrest-Thomson, in 2002. (It's my understanding that her premature death at the age of 27 is now considered to be accidental, rather than suicide.)

I sent Augustus Young an e-mail to see if he could tell me anything of Reed reading at "Poems for Shakespeare" in 1975. Mr. Young thoughtfully forwarded me to Anthony Rudolf, who had directed the event that year. Mr. Rudolf's gracious reply told me what I had already feared: Henry Reed did not appear; he was in hospital with one of his chronic illnesses, and could not be finally persuaded.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

The PN Review has revamped their website in the last year, adding a searchable index and full content for subscribers. Non-subscribers can still access the first few paragraphs of articles, as a preview.

Back in 2008, the PN Review featured Henry Reed's (until then) unpublished translations of Nobel Prize-winning Eugenio Montale's mottetti, edited by Marco Sonzogni, who provided a fascinating afterword describing Reed's manuscripts at the University of Birmingham.

On the PN review you can see a preview of Reed's translation of the first of Montale's motets:

The Pledge [Motet I] Lo sai: debbo riperderti e non posso.

Come un tiro aggiustato mi sommuove

ogni opera, ogni grido e anche lo spiro

salino che straripa

dai moli e fa l'oscura primavera

di Sottoripa.

Paese di ferrame e alberature

a selva nella polvere del vespro.

Un ronzío lungo viene dall'aperto,

strazia com'unghia ai vetri. Cerco il segno

smarrito, il pegno solo ch'ebbi in grazia

da te.

E l'inferno è certo. Several folks wrote letters to the Review following the publication of the Mottetti, to argue some of the finer points of Reed's translations. This issue and others are available for purchase from the Carcanet website.

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

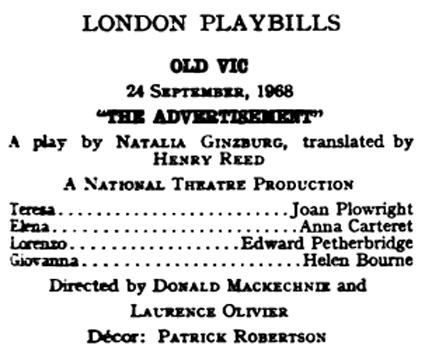

Playbill facsimile for the 1968 National Theatre production of Ginzburg's The Advertisement, translated from the Italian by Henry Reed, directed by Donald MacKechnie and Laurence Olivier. From Who's Who in the Theatre (1972), in the HathiTrust digital library.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

Did Henry Reed play a part, however small, in Vita Sackville-West's renouncement of poetry? In 1946, the Incorporated Society of Authors was charged with putting together a poetry recital of classic and modern verse for the Royal Family. A committee was convened, chaired by Denys Kilham Roberts (the Society's secretary-general), which included George Barker, Louis MacNeice, Walter de la Mare, Henry Reed, Edith Sitwell, Dylan Thomas, and Sackville-West.

Vita Sackville-West (cousin to Edward "Eddy" Sackville-West) was a prize-winning author and a poet, famous for her bisexual romances, including a long relationship with Virginia Woolf. By 1946 she had published fourteen novels, five scholarly biographies, and ten volumes of poetry (not including a Collected Poems in 1933).

In Henry Reed's review of Walter de la Mare's Complete Poems ( The Sunday Times, January 15, 1970), Reed makes mention that his first and only meeting with de la Mare took place at one of the meetings of the Poetry Committee:

On the one occasion I had the honour of meeting de la Mare—after some rather fractious gathering convened to decide which verses in our language might not be too tedious or indecent for the young ears of the Royal Family—I fervently recorded this fact to him. He was too modest to believe it; but eagerly, in a damp, dark Chelsea street, he told me of the barely credible circumstances of his first meeting with Hardy, in 1921.

It may be, perhaps, that the "damp, dark Chelsea street" Reed describes is somewhere in the vicinity of the offices of the Society of Authors, 84 Drayton Gardens, London.

At least one meeting took place in the King's Bench Walk offices of Denys Kilham Roberts, barrister at law; in order to choose which poems would be read at the recital, and by whom. In Victoria Glendinning's biography, Vita: The Life of V. Sackville-West (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1983), we have this account:

In March she went to a meeting of the Poetry Committee of the Society of Authors, chaired by Denys Kilham Roberts at his rooms near Harold's [her husband, Sir Harold Nicolson] old apartment in King's Bench Walk. The committee—which included Edith Sitwell, Walter de la Mare, Henry Reed, Dylan Thomas, Louis MacNeice and George Barker—was to plan a poetry reading to be held at the Wigmore Hall in the presence of the Queen. Vita made no comment in her diary at the time; only in 1950, in depression, did she write: 'I don't think I will ever write a poem again. They destroyed me for ever that day in Denys Kilham Roberts' rooms in King's Bench Walk.' (p. 341)

Sackville-West, whose long poem The Garden (London: Michael Joseph, 1946) was just about to be published, was not selected to read her verses for the Queen. "I am prepared to devote all my energies to the garden, having abandoned literature," she wrote, despairingly (Glendinning, p. 341). In truth, she was to end up devoting all her literary energy to gardening: in 1947 she began an immensely popular column for The Observer called "In Your Garden," and the following year became a founding member of the National Trust's garden committee. As a matter of fact, when I was attempting to define the species of flowers in Reed's "Naming of Parts," I turned to the second of Sackville-West's collected essays, In Your Garden, Again (London: Michael Joseph, 1953):

October 14, 1951 It started its career as Pyrus Japonica, and become familiarly known as Japonica, which simply means Japanese, and is thus as silly as calling a plant 'English' or 'French.' It then changed to Cydonia, meaning quince: Cydonia japonica, the Japanese quince. Now we are told to call it chaenomeles...[.] (p. 134)

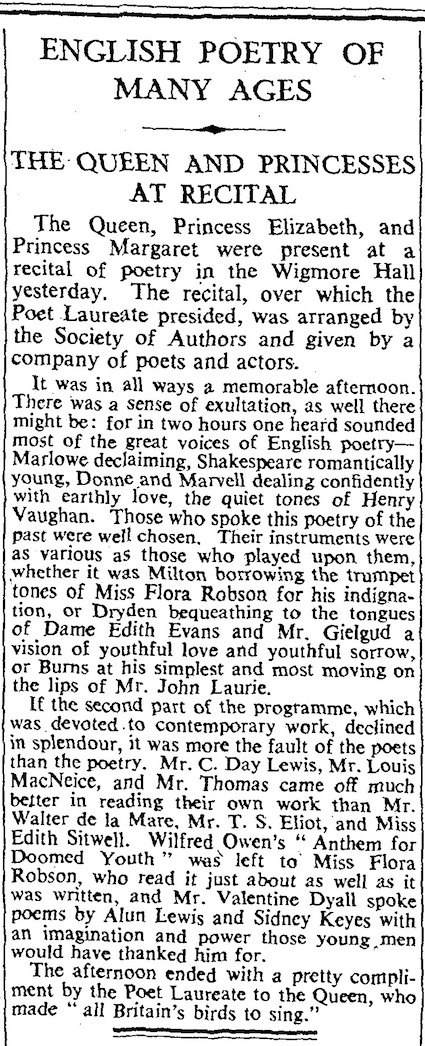

The recital took place on Tuesday, May 14, 1946, at Wigmore Hall. The Queen, Princess Elizabeth, and Princess Margaret were in attendance. John Masefield, the Poet Laureate, presided. The actors Valentine Dyall, Edith Evans, John Gielgud, John Laurie, and Flora Robson read classics of English verse, while C. Day Lewis, T.S. Eliot, Louis MacNeice, Walter de la Mare, Edith Sitwell, and Dylan Thomas presented a selection of more modern poems, which were somewhat less well-received. Thomas, apparently, "at one stage in the proceedings was seen to flick his cigarette ash in the Queen's lap" (Victor Bonham-Carter, vol. 2 of Authors by Profession. London: Bodley Head, 1984, p. 302). This announcement appeared the next day, in The Times:

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

While I was tracking down two references to book reviews Henry Reed had written for The Sunday Times, I unexpectedly discovered this critique of The Complete Poems of Walter de la Mare (Faber and Faber, 1969), " Solacing Music," from January 25, 1970. In a happy coincidence, it happened to appear in the first month of the first of many, many reels of microfilm I was whizzing through.

This particular review is especially interesting because not only does it outline Reed's personal feelings about de la Mare's poetry, but it also lets slip two personal anecdotes. The first is related to Reed's shared affinity for, and indebtedness to, Thomas Hardy and his poetry. Reed mentions having visited Hardy's second wife in 1936. Indeed, Florence Hardy wrote to Reed in December of that year, in an attempt to dispell his delusions about penning a biography of her late husband.

Reed goes on to describe his only meeting with de la Mare, which occurred 'after some rather fractious gathering convened to decide which verses in our language might not be too tedious or indecent for the young ears of the Royal Family.' This being in reference to a poetry recital which was held at Wigmore Hall in May of 1946 in honor of the Queen, Princesses Elizabeth, and Princess Margaret. Incidentally, it was the meetings for this poetry reading which would inadvertently cause Vita Sackville-West to swear she would never write poetry, again (more on that, later)!

Solacing music

Solacing music

THE COLLECTED POEMS OF WALTER DE LA MARE/Faber £5 pp984

HENRY REED

He could no longer listen to the reading of prose, though a short poem now and again interested him. In the middle of one night he asked his wife to read aloud to him "The Listeners," by Walter de la Mare. Thus Thomas Hardy on his deathbed: a tribute to both poets, for it is by no means easy—as I think Wordsworth was first honest enough to say—for a poet to make much of a poet a good deal younger than himself; and there was a difference of over thirty years between these two. What was it in de la Mare's great poem of desolation, disappointment and unresponse that Hardy wanted to hear said to him at that moment? Perhaps:For he suddenly smote on the door, even

Louder, and lifted his head:—

"Tell them that I came, and no one answered,

That I kept my word," he said. I have never, myself, wanted to know who the traveller or the listeners are in this poem, and have rather averted the gaze from any exegesis of it. But is this not in itself rather a despicable critical evasion of a kind which we have resigned ourselves to in the case of de la Mare?

Let me revert to Hardy. Though Hardy was kindly and hospitable to the many young poets who sought him out, de la Mare was the only one he was genuinely curious to meet. I am sorry I cannot "document" this statement: it was either told me by the second Mrs Hardy in 1936, or it is remarked on in one of the several thousand unpublished Hardy letters now being edited by Professor Purdy.

On the one occasion I had the honour of meeting de la Mare—after some rather fractious gathering convened to decide which verses in our language might not be too tedious or indecent for the young ears of the Royal Family—I fervently recorded this fact to him. He was too modest to believe it; but eagerly, in a damp, dark Chelsea street, he told me of the barely credible circumstances of his first meeting with Hardy, in 1921. I did not know that a retrospective poem on the subject was already in print. And his deeper feelings, expressed in the poem, he did not repeat: but they are worth repeating now:And there peered from his eyes, as I listened,

a concourse of women and men,

Whom his words had made living, long-suffering—

they flocked to remembrance again;

"O Master," I cried in my heart, "lorn thy tidings,

grievous thy song;

Yet thine, too, this solacing music, as we earthfolk

stumble along." The deliberate touch of pastiche in these lines, written round about 1938, is of course a kind of homage and does not make the poem less moving. It is very different from the real help he had sought from Hardy's poetry in 1921, or just before when, as Dr Leavis has acutely remarked, de la Mare seems to have recognised "the vanity of his poetic evasions . . . It is as if, in his straights, he had gone for help to the poet most unlike himself, strong where he is weak" [New Bearings in English Poetry. London: Chatto & Windus, 1950].

It is doubtful if he found this help. For some reason, after the publication of "The Veil" in 1921, de la Mare stopped publishing serious poetry (at least in England) and devoted himself to prose, and to comic verse. When I was an undergraduate, on the rare occasions when twentieth-century poetry was admitted to exist, de la Mare was occasionally mentioned, sadly withal, as one who had not fulfilled his promise.

This was quite agreeable to us: it meant we did not have to go and find out exactly what the promise had been. In any case we had, by then, Eliot and Pound, and they provided quite enough matter for thought, if thought was what it was we directed at them.

There was, however, a genuine feeling that de la Mare had ceased to exist. Then, in 1933, appeared "The Fleeting." But by this time we had Auden to cope with. And "The Fleeting" was much the same mixture as before, though longer poems like "The Owl," and "Dreams" (which mentions, not with much respect, the Id) had begun to appear and to threaten a boredom later to display itself more expansively. Other volumes, light or serious, followed. Towards the end there were efforts at the long "great" poem. "The Traveller" is often exciting and terrifying, but only in its last pages really impressive. As for "Winged Chariot," I have to confess to what may be a personal blackout. It is a long poem about time, chronometers, etc., and is often in its early pages humorous and engaging; the trouble is that though it is at no point unbeautiful, it is largely unreadable.

I am pedantic enough to wonder why the charming marginal glosses (like those of Hakluyt and Coleridge) of its first edition should have been inserted in this Collected Poems into the poem itself as though they were epigraphs to various sections of it—thereby rendering what is difficult enough virtually unintelligible.

Mr Auden does the same with it in his "Choice of de la Mare's Verse" and tells us, a little uneasily, that the poem "is better read, perhaps, like 'In Memoriam,' as a series of lyrics with a metre and theme in common." But surely for God's sake please, Tennyson's poem is a moving poem? We don't come out of it quite as we went into it; and we do not fall asleep during it.

In 1913, reviewing a "collected" Robert Bridges, de la Mare remarks: "The writing of verse easily becomes a dangerous habit." This is distressingly true of himself: there is simply and blankly and monotonously too much of him. In the same essay, he remarks: "Complete editions serve too often merely for an imposing monument" ["The Poetry of Robert Bridges." Review of The Poetical Works of Robert Bridges, Excluding the Eight Dramas. Saturday Westminster Gazette, August 30, 1913. Reprinted in Private View. London: Faber and Faber, 1953. 108-113.]. In the present volume his poems occupy, in fairly small print, pages 3 to 888. This is a lot of reading-matter. I cannot think its gentle author can have wished it all at once upon anybody.

(p. 57)

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

I hope I am not being too disingenuous with my title, but I did hit upon an unexpected windfall of Reed's book reviewing in The Sunday Times. Once again, a simple snippet in Google Book Search was enough to lead me to three articles by Reed from 1969 and 1970, including " Two Years Before the Muse": a review of William Cooke's biography of Edward Thomas which appeared on March 29, 1970:

Two years before the muse

Two years before the muse

EDWARD THOMAS: a critical biography by William Cooke

Faber 50s

HENRY REED

FLAWLESSLY and confidently though he himself can write, Mr Cooke does not hesitate, in this fine book, to withdraw himself when necessary, and with excellent judgment to let his subjects—for there is Helen Thomas as well as Edward—have their own say: as they both eloquently could. And since Thomas and is wife, despite difficult passages, were never enemies, Mr Cooke's book moves the reader in a way that biography rarely does: his second chapter, "The Divided Self," is a model of well-selected documents, in both poetry and prose, brought together, properly digested, and firmly handled.

He has, of course, a subject where, biographically at least, there seems little need for guesswork. Thomas himself was a self-declared depressive, often took laudanum, and was on occasion determined on suicide. Mr Cooke is fully aware of the justifiable self-pity of both Edward and Helen. It is balanced by their pity for each other and their candid understanding and acceptance of each other.

Certainly Thomas himself, through the whole of his fantastically overworked life as a hack journalist and a writer of "deadline" commissioned books, gives the impression of someone who could not easily tell lies, and the well-known portrait of him (a trifle blurred in this volume) gives the feeling of someone who could not easily believe in them either.

And truth is a useful thing. Curiously, his candid avowal that Helen loved him more than he loved her produces one of the finest love-lyrics in the language. It ends:Till sometimes it did seem

Better it were

Never to see you more

Than linger here

With only gratitude

Instead of love

A pine in solitude

Cradling a dove. An even more sombre candour informs the poem about his father, withheld from the brief Collected Poems till twenty-two years after the poet's death. It is not at all a poem about hate, but it begins:I may come near loving you

When you are dead and ends:But not so long as you live

Can I love you at all. His father survived him.

Apart from conventional juvenilia, Thomas wrote no poetry before the age of thirty-six. Hitherto he had confined himself to twenty-nine books of prose. He was to live about two years more; and despite its many outstanding virtues, the most astonishing and valuable part of Mr Cooke's book is the appendix in which he establishes the chronology of these two incredible years: I quote merely its beginning: 1914

3 December "Up in the Wind"

4 December "November"

5 December "March"

6 December "Old Man"

7 December "The Sign Post" And these poems are by no means dilettante haiku. Some are of notable length. It is to be hoped that the elegant pages of the Collected Poems may as a result of Mr Cooke's researches, soon be rearranged chronologically.

Thomas's switch to poetry (much of it, and some senses all of it, remarkable: it had the rare distinction of never appearing in "Edward Marsh's "Georgian" collections) has been variously explained, Robert Frost, older, but not much older, and first published in England, had said to him: "You are a poet or you are nothing." But a man does not became a poet simply because he is told he is one; though doubtless Frost's remark struck at something Thomas had wanted to, yet dared not, until then, think of.

But these things are, as psychoanalysts say "over-determined." I am not so much entranced as I once was by the observations of analysts on what they call "creativity": but what the distinguished analyst Dr Elliott Jaques in an essay on what he terms the "mid-life crisis" devotes his early pages to artists in their middle thirties—the mezzo del cammin of Dante. He examined a "random sample" of 310 artists of genius (one had not thought death had undone so many!) who had exemplified this mid-life crisis in three different ways: either their career ended at this time; or it began (one thinks of Conrad); or a decisive change took place in the quality and content of their work. (One might add that some artists re-begin at this age: I am thinking of our own Jane Austen.)

I think that Edward Thomas, if not decisively a genius, fits well enough into all this. Dr Jaques connects his thesis with our realization at this age that death does actually exist, and is probably nearer to us than birth. Thomas thought often of death. He was not strictly of conscribable age, and had every opportunity of joining Frost in America. But he decided to enlist, and was apparently certain that he would not see his beloved England again. He wrote no more poetry once he landed in France; and it could be said of him by Alun Lewis, also writing of death, and himself prematurely killed in a later war:Suddenly, at Arras, you possessed that hinted land. (p. 56)

You can read more about Edward Thomas on the Friends of the Dymock Poets website.

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|