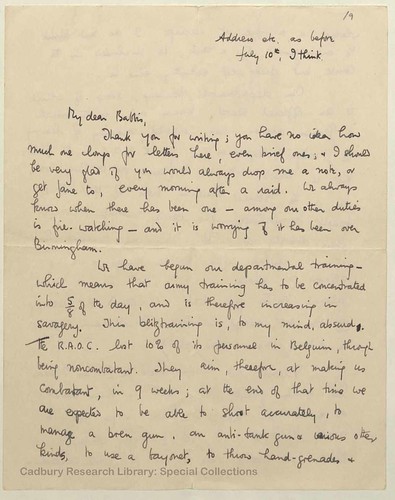

One of the more important items (or, at least, important to me), is a letter Reed wrote to his sister Gladys (affectionately called "Babbis," married to Joe; Henry, is of course, Prince "Hal" to his family). This letter was quoted by Professor Jon Stallworthy for his Introduction to Reed's Collected Poems (Oxford University Press, 1991; Carcanet, 2007), and was written at nearly the same time as another (similar) letter to John Lehmann: during the summer of 1941, during the Birmingham Blitz and close on the heels Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union, whilst Reed is in the midst of his basic training, expecting to be sent into combat and doubtful of his effectiveness:

Letter from Private Henry Reed, to his sister Gladys in

Birmingham, July 10, 1941. Cadbury Research Library

Special Collections, University of Birmingham.

I hope to find time to transcribe more of these letters from Henry. Click here to see the University of Birmingham Special Collections' catalog record for Henry Reed's letters to his family.Address etc. as beforeMy dear Babbis,

July 10th, I think

Thank you for writing; you have no idea how much one longs for letter here, even brief ones; and I should be very glad if you would always drop me a note, or get Jane to, every morning after a raid. We always know when there has been one — among our other duties is fire-watching — and it is worrying of it has been over Birmingham.

We have begun departmental training — which means that army training has to be concentrated into 5/8 of the day, and is therefore increasing in savagery. This blitztraining is, to my mind, absurd. The R.A.O.C. lost 10% of its personnel in Belgium, through being noncombatant. They aim, therefore, at making us combatant, in 9 weeks; at the end of that time we are expected to be able to shoot accurately, to manage a bren gun, an anti-tank gun and various other kinds, to use a bayonet, to throw hand-grenades and

[Page 2]:

whatnot and to fire at aircraft. I do not think the management of a tank is included in the course, but pretty well everything else is.

Our departmental training, some of which is an official secret, known only to the British and German armies, has consisted mainly of learning the strategic disposition of the R.A.O.C. in the field: this is based, not, as I feared, on the Boer War, but on the Franco-Prussian War of 1871. It is taught by the lecturers who rarely manage to conceal their dubiety at what they are teaching. But it is restful after the other things, and we are allowed to attend in P.T. 'kit'. This is nicely balanced by the fact that we attend P.T. wearing all our 'kit', except blankets. (I will never call a child of mine Christopher.)

Please let mother have the £1, as I know how much greater her need is than mine; I do assure you that I have, so far, all the money I need. I get £1 every Friday, and should get more, were it not for some compulsory

[Page 3]:

voluntary deduction which they make; and I don't seem to spend even £1. I am still too tired to go out much at night, the beer here is undrinkable and I am having to give up smoking, as my lungs will not stand the strain of smoking and the other things they are called upon to do. So, I am comparatively well off; I should be glad of some more cheques: as this will be my last chance of paying much to my debtors I thought I'd better pay them all a little bit. This, I'm afraid involves a lot of cheques, and if you could let me have another half dozen, it would greatly help me.

I should be glad to have the New Statesman, if that is possible; it comes out on Friday, and if I got it by Saturday that would be marvelous.

I hope a good deal from Russia, of course, but rather joylessly: the scale of it all is beyond my grasp, and it is terrible to see a country

[Page 4]:

which, with all its faults, has been alone in working to give the fruits of labour to the people who have earned them, thus attacked; I think you should think about Russia very seriously, and try to learn something about her, and try to find why she can perhaps do things that we cannot — things that France, for example, could not. Stalin and Molotoff may be bureaucratic villains: I don't know. But if they are, they are only the passing evil which cannot wipe out what the period of Lenin gave. While we — we are only beginning to turn up a little doubtful virtue in our rulers, after decades of Chamberlain big business. And big business still can stifle the efforts at wise government here, as any workman you meet on a train will tell you. The British people are fighting a battle on two fronts, at home and against Germany: so far we have only been able to hurt Italy, who is fighting a battle on three: against us, against the banker-princes,

[Page 5]:

and against Germany also; Russia has fought, and largely won, her battle against capitalism. She is only fighting Germany now. That is why she may win; without that earlier victory, her enormous size would avail her nothing in these days. And when she is secure against fascism (which isn't confined to Germany and Italy) perhaps the horrible side of Russia will fade away more rapidly than now seems possible.

I don't know what to say about Joe. It is clear that an officers' mess is a decadent place, even if there are in it people as gallant and intelligent as Joe and a few of my own friends who have recently got commissions; I gather that an officers' mess is boring and dull, and therefore easy to set up expensive forms of distraction in; and I suppose most of Joe's companions were regular commissions officers, who are usually stupid and illiterate (our Lieut-Col. told us we were now fighting alone, last

[Page 6]:

week, since France failed us; I suppose he hadn't heard about Russia) and they may lead him astray, which could happen very easily, I think, knowing Joe. If you think telling him about the O.D. would shock him into remorse, do so; I think this would be the best way. It means great inconvenience to you, always to shoulder Joe's burdens like this, but eventually it ought to aruse his conscience. The time for a general settlement will be after the war is over; everybody will be so shatteringly poor then, that things will probably settle themselves, even overdrafts.

The enclosed is a present (not a repayment — not yet) from me; I am keen on its being divided thus, and thus only: 5/- for mother (for her birthday), 1/6 for Jane (because why should she have any more than that) and 13/6 for you (to be spent as "pocket-money"

[Page 7]:

on oddments, meals and so on, because by now you ought to be learning what it feels like to have 13/6). Please do this arrangement for me, as faithfully as if it were a will.

And write again soon.

All my fondest love to you all.

Hal.