At long last — and long sought-after — David Lodge's 1983 documentary on Birmingham writers in the 1930s, "As I Was Walking Down Bristol Street," is available online, in its entirety. Lodge, an author and critic, was Professor of English Literature at the University of Birmingham from 1976 until 1987.

The film gives a short history of the authors who made up the Birmingham Group, primarily Walter Allen, Walter Brierley, Leslie Halward, John Hampson, Reggie Smith, and by association, Louis MacNeice and W.H. Auden. Allen and Smith, both old school chums of Henry Reed from Edward VI Grammar School, Aston (and later at university) give interviews for the film.

A highlight is the story how of Auden would introduce his heterosexual friend: "This is Reggie Smith. He's not one of us, my dear, but we have hopes for him."

Henry Reed is mentioned by Smith at around the 23-minute mark, in a famous anecdote regarding Louis MacNeice's farewell party, when he was leaving Birmingham University for Bedford College, in 1936. Smith recalls:

"That was where Henry Reed nearly had his arse burnt off because somebody — well it wasn't somebody, it was the director from the Group Theater [Rupert Doone] — who got himself into a great state of anguish because he'd just done — he was talking to professor Dodds, this big man was explaining to him that he always saw it as a "fountain of blood, you see an idea: I see it as a fountain of blood" [for a production of MacNeice's Agamemnon] and Dodds said 'you'd find that a bit difficult perhaps to put on the stage' and he got very hurt at that suggestion and said 'I don't care' and threw his vodka into the fire which leapt out, like a flame, and burnt the backside of Henry Reed, who was minding his own business at the fireside. But it's a party that went on for days and days."

The film has Lodge in MacNeice's former flat above the coach house at Highfield, Selly Park, where the legendary party took place.

|

As I Was Walking Down Bristol Street

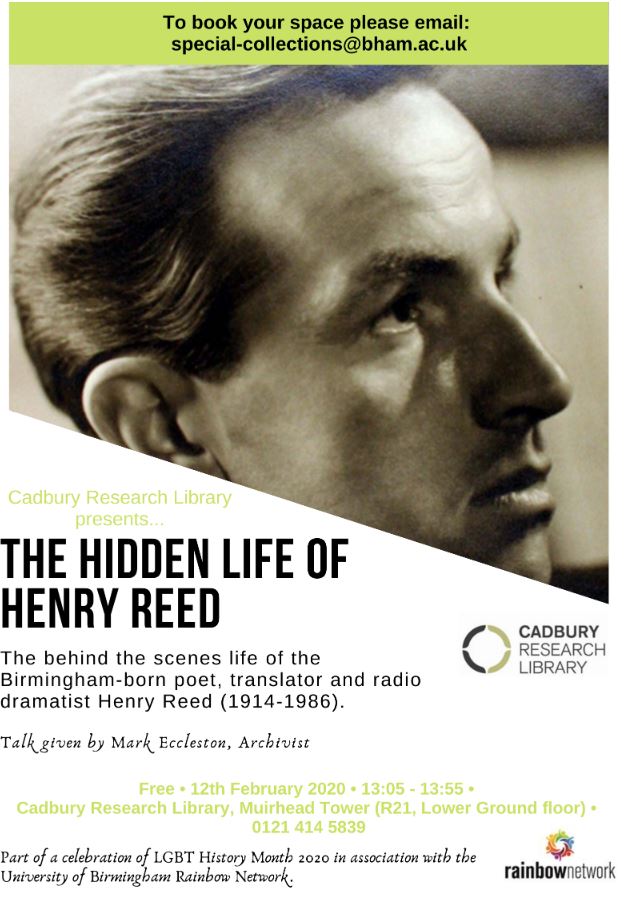

The Hidden Life of Henry Reed, RepriseOn Wednesday, February 12th, Mark Eccleston, archivist at the University of Birmingham's Cadbury Research Library, will again deliver a talk on everyone's favorite Birmingham-born poet, translator and radio dramatist: "The Hidden Life of Henry Reed." Part of a celebration of LGBT History Month, 2020.

LOLReed VI

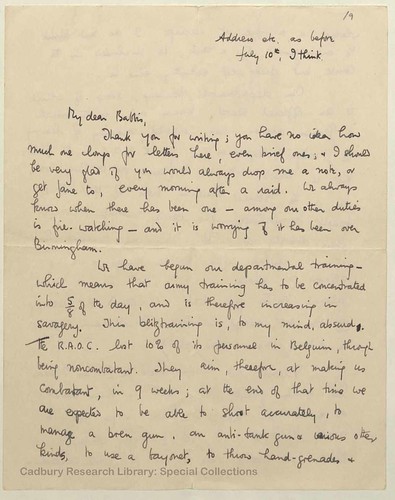

Letter from Private Henry Reed (July 1941)The Cadbury Research Library at the University of Birmingham, for Henry Reed's centenary, has very thoughtfully made available some selections from the Reed's papers on their Flickr page: Henry Reed: Behind the Scenes. There are scans of some of Reed's early writings from the University magazine, The Mermaid, photographs, and letters (slideshow).

One of the more important items (or, at least, important to me), is a letter Reed wrote to his sister Gladys (affectionately called "Babbis," married to Joe; Henry, is of course, Prince "Hal" to his family). This letter was quoted by Professor Jon Stallworthy for his Introduction to Reed's Collected Poems (Oxford University Press, 1991; Carcanet, 2007), and was written at nearly the same time as another (similar) letter to John Lehmann: during the summer of 1941, during the Birmingham Blitz and close on the heels Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union, whilst Reed is in the midst of his basic training, expecting to be sent into combat and doubtful of his effectiveness:  Letter from Private Henry Reed, to his sister Gladys in Birmingham, July 10, 1941. Cadbury Research Library Special Collections, University of Birmingham. I hope to find time to transcribe more of these letters from Henry. Click here to see the University of Birmingham Special Collections' catalog record for Henry Reed's letters to his family.

A.M.D. HughesIn his article, "John Clare's Learning," published in the John Clare Society Journal in 1988, Eric H. Robinson relays the following anecdote:

I remember the poet, Henry Reed, telling me of a professor at Birmingham University, where Reed studied, who told him that he must correct his grammar before he could become a poet. Reed did so: Clare not only did not do so, but after some early attempts resolutely refused to comply. [p. 11] Henry Reed attended the University of Birmingham from 1931 until 1936. Who was this professor who taught him proper grammar and helped mould him into a modern poet? An answer appears in The Listener for September 28, 1972, in the schedule of upcoming radio programmes:  You can browse the rather daunting list of Hughes's books and publications on WorldCat. Anthony Thwaite, reviewing recent radio for The Listener on October 26, had this to say about the formidable professor's appearance: The strangest and certainly most moving talk programme of the week was A.M.D. Hughes's Personal Anthology on Radio 3, which among other things demonstrated—in this period of celebration, when the supposed golden age of radio must often be sounding on tin ears—that old men do not forget. Hughes, approaching his 100th year (Radio Times got this right but R.D. Smith, introducing him on the air, managed to lop off a decade), used to teach English to, among other, the young Henry Reed and Kingsley Amis. He recited out of his blindness Hardy, Milton, Wordsworth, Arnold and Shelley, with an exalted and totally unfashionable inflection that demanded complete attention. He certainly got mine. For his performance of 'The Convergence of the Twain' alone this programme deserves a place in the archives, along with those crackling atmospheric fragments of Browning and Tennyson. ["Jabbering Set," p. 560] Incidentally, R.D. "Reggie" Smith also would have been a student of Hughes's at Birmingham, along with Reed and Walter Allen. Arthur M.D. Hughes died on January 11, 1974. His obituary appeared in The Times, the following Monday: Eric Robinson also mentions Reed in his acceptance speech for the Leonardo da Vinci Medal, given at the awards banquet of the annual meeting of the Society for the History of Technology in Las Vegas, in 2006: I began my life of archival research in the Birmingham City Reference Library at the age of eleven, when I went there in the evenings to do my homework. A happy, rotund lady called Miss Norris used to help me by bringing me books, but also manuscripts from the Boulton and Watt Collection. As a junior librarian (aged sixteen), she herself had compiled the first catalog of that great archive, and it was amazing what she could find in it. It's one thing to read about James Watt's engines, and another to look at the splendid colored drawings that Watt submitted in order to get a patent. A few years later, I was being taught at King Edward VI Grammar School in Aston, Birmingham, by the poet Henry Reed. He introduced me to the poetry of Auden. I read for the first time poetry whose visual images reinforced my own daily experiences...[.] [Technology and Culture 48, no. 1 (2007): 133] And so the circle of teaching is complete!

Birmingham in the 1930sHere's a customized Google Map providing interactive literary landmarks for Birmingham, England, during the 1930s, which intersects nicely in several places with our own map of Henry Reed's life. This map appears to have been created in conjunction with a recent screening of As I Was Walking Down Bristol Street (1983), a short documentary film on the Birmingham Group of writers and artists. More detailed information about the places and people described is provided on mike in mono's blog, with spectacular posts on the authors Walter Allen and John Hampson; Gordon Herickx, the sculptor; the Highfield estate (Louis MacNeice lived in a flat above the coachhouse while he was a professor at the University of Birmingham); and Professor E.R. Dodds.

Henry Reed's HouseThis post is about as real as research gets. It's international! It's got everything—from old, primary source documents, to cell phone pics! Reed on, read on:

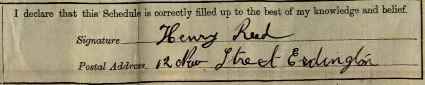

Almost three years ago, I was thinking on the famous blue plaques put up by England's Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission, and lamenting that Henry Reed may never get a marker devoted to him, either in London or Birmingham, unless the buildings he once lived in could be found, and were still standing. Here are the first two paragraphs from Professor Jon Stallworthy's introduction to the Collected Poems, which provides the most insight to Reed's early life: Henry Reed was born, in Birmingham, on 22 February 1914 and named after his father, a master brick-layer and foreman in charge of forcing at Nocks' Brickworks. Henry senior was nothing if not forceful, a serious drinker and womanizer, who as well as his legitimate children fathered an illegitimate son who died during the Second World War. In this, he may have been following ancestral precedent: family legend had it that the Reeds were descended from a bastard son of an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century Earl of Dudley. Henry senior's other enthusiasms included reading, but the literary abilities of his son Henry junior seem, paradoxically, to have been inherited from a mother who was illiterate. Born Mary Ann Ball, the eldest child of a large family that had migrated from Tipton to Birmingham, she could not be spared from her labours at home during what should have been her schooldays, and when, in her late middle age, her granddaughter tried, unsuccessfully, to teach her to read, she wept with frustration and shame. Mary Ann Reed had a remarkable memory, however, and a well-stocked repertoire of fairy-stories—told with great verve—and songs to enchant her children and grandchild. A daughter, Gladys, born in 1908, was encouraged to make the most of the schooling her mother had not had. She was a good student and in due course became a good teacher, discovering her vocation in teaching her younger brother. Gladys played a crucial role in the education of Henry (or Hal, as he was known in the family, a name perhaps borrowed from Shakespeare's hero) and was to become and remain the most important woman in his life. He was not an easy child. On one occasion dismembering his teddy bear, he buried its head, limbs, and torso around the garden and went howling to his mother. She was obliged to exhume the scattered parts, wash, and reassemble them for the little tyrant. At the state primary school in Erdington, he clashed with a hated teacher who pronounced him educationally subnormal. A psychiatrist was called in and, having examined the child, claimed to have detected promise of mathematical genius. I was excited to discover, just earlier this year, Reed's old London flat, when Google Maps UK went live with Street View. Now, owing entirely to some clever sleuthing by an Erdington native, we have the location of Henry Reed's birthplace and childhood home (not to mention, his teddy bear graveyard). Back in August, I received an e-mail from Ms. Molly James, who was concerned that Reed is not better known in his hometown, but hopeful that the Birmingham Civic Society might still properly commemorate their native son with a plaque of his own. Molly began her research in a place I shamefully never even considered: the U.K. census. There, in the rolls for 1911, we find the family of Henry senior, living in Erdington:  The census website requires the purchase of credits to view their documents, but I can tell you that the schedule lists, living in their four-room cottage: Henry Reed, 26 years old, "Setter at Brick-kiln"; his wife, Polly Reed, 35, "at Home Work"; and daughter Gladys, just two years old. The couple had been married five years, having moved from Tipton, to the west, sometime after Gladys was born. The Reeds' son, Henry junior, would not be born for another three years—and the next census from 1921 is not yet public—but on this information alone, Molly generously went 'round and took a few snapshots of the address (click to see larger image): Spectacular! But Molly didn't stop there. She got in touch with archivist Jim Perkins, whom you might remember as the keeper of all things related to King Edward VI Grammar School, Aston. Mr. Perkins confirmed that the 1911 address was registered as Reed's home when the budding poet entered KEGS, Aston, in 1925. I'm grateful for the hard work and devotion of Ms. James, and proud to add this first and preeminent location to the map of Henry Reed's life (which recently hit over 10,000 views!). Thank you, Molly! We'll see that blue plaque, yet!

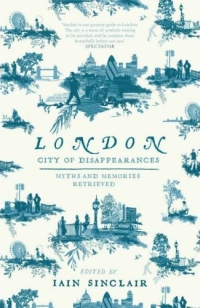

ConnectionsI returned recently to a book I first looked at back in October of 2006: London: City of Disappearances, edited by Iain Sinclair. A huge collection of stories about a London which no longer exists (or never was), it contains a small chapter by Richard Humphreys, "Death of a Cleaner," in which Humphreys attempts to discover something, anything, about his London house cleaner's enigmatic life, following the man's untimely death. 'Not everyone has a house cleaner who knew Dylan Thomas and Francis Bacon,' Humphreys begins, 'and who was born into an aristocratic family and went to Wellington College and Cambridge University. I had one, called Mr [Antony] Ashburner, and he disappeared from my life as suddenly as, fifty years before, he had disappeared from the life of his own family.'

I was surprised, on re-reading the chapter, on how many connections and confirmations to the story I had uncovered in the last two years, in the span of a couple of paragraphs: I cannot follow them into their world of death, Or their hunted world of life, though through the house, Death and the hunted bird sing at every nightfall. henry reed, 'Chrysothemis' According to his sister, [Ashburner] went up to Cambridge in 1939 to read law. If he did go to Cambridge it didn't suit him and he transferred to Birmingham, where he probably read English. There is a mysterious and evocative poem by the Birmingham poet Henry Reed, called 'Chrysothemis',1 which gives an insight into Ashburner's life in the Second City. After his death, I found a galley proof of the poem in his untidy flat at the wrong end of Ladbroke Grove. There was a dedication, handwritten in ink: 'To Antony from Henry, December 1942'. The poem is darkly Eliotic and casts light on an important, if brief, relationship. It was published in John Lehmann's New Writing and Daylight that winter. In a letter of 1965 — to Dorothy Baker,2 a BBC Third Programme script-editor — Ashburner recalls this acquaintance during a brief spell when he was living in the basement flat of a house belonging to Professor Sargent Florence, the left-wing economist and sociologist. This was Highgrove,3 a Birmingham house famous enough to be the subject of a short TV film by David Lodge.4 Ashburner's flatmate was Dr Bobby Case, a pathologist at St Chad's Hospital. 'I wondered then,' he wrote to Baker, 'and I have sometimes wondered since, how it was that Bobby Case managed to get hold of so much offal for our dinners — in view of wartime shortages. . .' Highgrove, a large house, now demolished, was the haunt of writers and radicals, such as Auden and Spender, as well as the novelist and Birmingham University lecturer Walter Allen5 — whose name can be found in Ashburner's surviving address book. Highgrove was a Midlands bohemian hang-out unknown to most metropolitans. Perhaps, like Julian Maclaren-Ross,6 another acquaintance, Ashburner was one of the misfits and deserters incarcerated in the psychiatric wing of Northfield military hospital [Wikipedia] in the Birmingham suburbs, one of W. R. Bion's [Wikipedia] patients (guinea pigs). What else did he do in the war? Reed went on to work at Bletchley Park. My mother-in-law, who was in the same section, remembers him taking a female colleague out for lunch. Reed's Bletchley Park friend, Michael Ramsbotham, has no recollection whatever of Ashburner. Was he a conscientious objector? In my more fanciful moments I imagine he was a spy, although I'm not sure which side he would have been on. By the end of the war he was living in Fitzrovia and working at Foyles bookshop. He wasn't keen on Christina Foyle [Wikipedia], he told me. 1. ^ Reed's poem, "Chrysothemis," is a monologue spoken by the daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemestra, sister of Orestes and Electra. The poem is quoted at length in Gross's Sound and Form in Modern Poetry. 2. ^ Dorothy Baker shows up as part of Conroy Maddox's Birmingham entourage in Silvano Levy's The Scandalous Eye. 3. ^ Highfield Cottage (not "Highgrove", as Humphreys would have it), was the home of Louis MacNeice while he was a lecturer in Classics at the University of Birmingham in the 1930s. The house is one of the landmarks in this map of The Life and Times of Henry Reed. 4. ^ The television documentary in which Highfield figures prominently is As I Was Walking Down Bristol Street. 5. ^ Walter Allen was a schoolmate of Henry Reed's at King Edward VI Grammar School, Aston, and both men went on to the University of Birmingham. 6. ^ Henry Reed seemed to have a special hatred of Julian Maclaren-Ross, and wrote several negative reviews of his work for the New Statesman. In his book, Fear and Loathing in Fitzrovia (2003), Paul Willets quotes one review in particular, from March 2, 1946: Like its predecessor, Bitten By the Tarantula attracted some scathing reviews. And, once more, the severest of his detractors was Henry Reed, whose hatred of Julian's work was fortified by a hatred of Julian himself. 'Mr Maclaren-Ross's book,' he wrote, 'is very well bound and generously, though not elegantly printed; but its last three pages increase their number of lines from thirty-four per page to forty-one, thereby giving a peculiar stretto effect to the narrative which is, in fact, its sole interest. [...] The point of Mr Maclaren Ross's novel is not obscure. It has none.' (p. 189) In defense of his character, Maclaren-Ross had an ally at the BBC in producer Reggie Smith, also a Birmingham colleague of Reed's. City of Disappearances is due out in paperback this fall.

Birmingham Under the BlitzBetween August 8, 1940 and April 23, 1943, the city of Birmingham in England's West Midlands suffered 77 separate bombing raids by the German Luftwaffe. The city endured a total of 365 air raid alerts. The intended targets were the region's indispensable aircraft, transportation, and arms industries. All told, German air attacks destroyed 12,391 homes, 302 factories, 34 churches, halls and cinemas, and more than 200 other buildings. The human cost of the "Birmingham Blitz" (Wikipedia) was a total of 9,000 casualties, of whom 2,241 were killed. This is second only to the damage inflicted on London during the war.

There is an excellent slideshow depicting the aftermath of the attacks on the Birmingham Air Raids Remembrance Association (BARRA) website. In a 1996 interview, the Surrealist painter Conroy Maddox (previously) mentions two incidents when he took shelter with Henry Reed during the Birmingham air raids, once in a public bathroom, and again at Birmingham Town Hall: Well, I suppose the significant moments were dodging the bombs as you fought. Henry Reed, the poet, was in Birmingham at that time, and lots of other people, and I remember being with him once, we were walking near Aston, and suddenly we heard bombs falling around, the alarm had already gone off, so we went down to a public lavatory. And of course women did as well, to get out of... it seemed a fairly safe place. But it was a bit embarrassing for the women, you know. But, we just sat on the books we had. And I always remember the book I had, which was Nicolas Calas's "Confound the Wise" (WorldCat), which is a glorious study of course, and I remember sitting on that on these cold slabs, you know, for hours on end until the alarm, the all-clear went off. Henry Reed and I once, a lot of people sheltered in the town hall under the arches, but we decided not to stay with the crowd but went up on the balcony and sat there. It wasn't until the light came that we realised it was a glass skylight, which wasn't very safe. But, no, I mean, the other thing of course was, you didn't know what was going to happen, I mean you just, you went to parties one night, you stayed up, or lounged around all night; you had to work the next morning, and you would go to another party the next night, you know. (F6321B, page 24) The interview was conducted by Robin Dutt at Maddox's home in London, as a part of the National Life Stories collection: Artist's Lives project, and is available through the British Library's Archival Sound Recording service. There is a full transcript of the interview (208 page .pdf), but audio is only available in the U.K., and requires an Athens ID. Maddox had been "reserved" from military service during World War II, as he was working in the engineering and design industry, so I'm not entirely sure what he meant by "dodging the bombs as you fought". In the interview he remembers thinking: 'I don't really want to be in the Army, all this walking the troops that, you know, soldiers do. Flying I didn't believe in, you know, and as for the Navy, well you know, they still had that idea of women and children first. I wasn't in favour of any of these things' (F6321B, page 21). It's easy to see why Maddox and Reed were friends. I wonder what book Reed was sitting on, in the loo?

Generals, Giants, and ConjurersIn 1930, at the beginning of his professional career, Louis MacNeice took a post as an Assistant Lecturer in Greek at the University of Birmingham. Despite finding it difficult to adjust to life in Birmingham after coming up at Oxford, and discovering that work and married life were somewhat at odds with his creativity, during this time MacNeice managed to publish his first novel and his second collection of poetry.

According to Alec Reid in Time Was Away: The World of Louis MacNeice (Google Book Search), in 1934 MacNeice had written to his friend Anthony Blunt that he was working on no fewer than five projects for publication: '1 Poems; 2 Novel; 3 Play; 4 Latin Humour; 5 Analytic Autobiography' ("MacNeice in the Theatre," p. 73). It's the play that MacNeice was working on during this time that is of interest, here. Reid elaborates: According to William T. McKinnon, the play MacNeice hoped to see published in 1934-5 is 'presumably' Station Bell. It had given him [MacNeice] a great deal of trouble and was still unfinished by 8 June 1934. A note, probably in MacNeice's writing, attached to an imperfect copy of the play in the Library of the University of Texas at Austin reads 'completed c. 1935, performed by the Birmingham University Dramatic Society c. 1936.' Making all allowances for textual imperfections, Station Bell is a strange work. Written in an obviously 'Irish' idiom and set in Dublin in the near future, it centres on the seizure of political power by a female 'nationalist' dictator, Julia Brown, and on her unsatisfactory marriage to a tired but essentially humane and balanced academic. The other principal characters are a shabby military leader, a testy capitalist complete with saxophone, and a mad clergyman who is dispensing drink in a station bar in Act I and eloping for America with Julia in Act III. In between there is a very funny scene in which Julia and the General recruit a Propaganda Corps to represent the brave new Ireland. This includes a negro Celt who can dance an Irish jig, a mannequin complete with toy dog representing an ancient Irish wolf-hound, a conjurer, Séamus Stein, who materializes glasses of Guinness out of thin air, an epileptic drummer, and two Carnival giants. The Birmingham production, with a cast including Walter Allen, R.D. Smith, and Henry Reed, seems to have been a somewhat hasty affair (p. 74). (Presumably, Reid is referring to McKinnon's book, Apollo's Blended Dream: A Study of the Poetry of Louis MacNeice [OCLC WorldCat]. I'll have to check that out.) So, here we have four friends who would go on to become powerhouses of the 'thirties and 'forties, putting on a play together at university: MacNeice, Walter Allen, Reggie Smith, and Henry Reed. I can't help wondering, reading the description of the play (which was never published or performed professionally), what were their respective roles? Did Reed play the 'mad clergyman'? The conjurer? The corrupt general? The answer is probably buried in the annals of the University of Birmingham's student magazine, The Mermaid. Reid quotes a March, 1937 review of the university production: Mr. MacNeice is fairness itself. And since his frankness is both flattering and amusing, we had an evening of high jinks with the Dublin dictatress, giants and generals. The play has slapstick, satire and moments of real tension. I could not tell how much the failure to knit together as a whole was due to the hasty charade-like production and how much was due to the author's liking for action on various planes and his tendency to do too many things at once. In retrospect it is possible to appreciate the device reconciling the dictatress and her husband against the background of fumbling giants; in the theatre it can only be fidgety (p. 75). There is also a handwritten fragment of the Station Bell in MacNeice's papers at the Berg Collection of English and American Literature at the New York Public Library, and I see only one other reference to the play being produced: at Manchester University by the amateur "Unnamed Society" in 1937.

Blue CirclesHenry Reed died December 8th, 1986, in St. Charles Hospital, London. This December marks the twentieth anniversary of his death.

This landmark makes Reed eligible for one of English Heritage's famous Blue Plaques, which adorn London landmarks once inhabited by eminent contibutors to the arts or industry. Some notable contemporaries of Reed's who have been awarded plaques include: Sir John Betjeman (31 Highgate West Hill), Sir Arthur Bliss (1 East Heath Road), Benjamin Britten, O.M. (173 Cromwell Road), C. Day-Lewis (6 Crooms Hill), T.S. Eliot, O.M. (3 Kensington Court Gardens), Louis MacNeice (52 Canonbury Park South), Dame Edith Sitwell (Greenhill, Hampstead High Street, Flat 42), and Dylan Thomas (54 Delancey Street). Among other requirements, to be eligible for a Blue Plaque a person must:

There is good news, however. The Birmingham Civic Society already has plans to erect a Blue Plaque dedicated to Reed in their city during the centenary of his birth, in the year 2014 (see future plaques). W.H. Auden already has one (see this gallery of Blue Plaques in Birmingham). Also scheduled to receive plaques in Birmingham are Walter Allen (in 2011), and Louis MacNeice (2013). At any rate, on Friday, December 8th I'll be stopping down at the local pub after work, to honor Mr. Reed's memory with one his favorite pastimes: having a few drinks. I'm buying!

Mysterious AppearanceAn intriguing e-mail from a visitor appeared in my inbox this morning, regarding a cameo appearance of Reed in a newly-published book, London: City of Disappearances, edited by Iain Sinclair (London Times review). The book is a collection of myths and mysteries of a London lost to time — stories of disappearing people, streets, pubs, and occupations — with contributions from J.G. Ballard, Marina Warner (Guardian excerpt), Will Self (Penguin extract), Alan Moore, and Michael Moorcock.

Reed materializes in "Death of a Cleaner" by Richard Humphreys, 'a portrait of a mysterious character called Antony Ashburner.' There is a mysterious and evocative poem by the Birmingham poet Henry Reed, called "Chrysothemis," which gives an insight into Ashburner's life in the Second City [i.e. Birmingham]. After his death I found a galley proof of the poem in his [Ashburner's] untidy flat at the wrong end of Ladbroke Grove. There was a dedication handwritten in ink: 'To Antony from Henry December 1942.' The poem is darkly Eliotic and casts light on an important if brief relationship... The poem in question first appeared in John Lehmann's wartime anthology New Writing and Daylight (Winter 1942-1943), and is a long monologue in the voice of Chrysothemis, the passive sister of vengeful Orestes and Electra, children of Agamemnon and his murderous wife, Clytemnestra. Lengthy excerpts from the poem appear in Harvey Gross's metrical study from Sound and Form in Modern Poetry (1964). Many thanks to John for alerting me to this! I can't wait to get a hold of a copy of City of Disappearances.

Surrealism in BirminghamThe artist Conroy Maddox (Guardian obituary) discovered Surrealism in 1935, when he was twenty-two, browsing through a book on European painting in the Birmingham City Library: Wilenski's The Modern Movement in Art (1927, rev. ed. 1935). Maddox had been born in Ledbury, Herefordshire in 1912, but his family settled in Erdington in 1933.

Although he eventually outgrew the city, Maddox was inspired by urban Birmingham—with its libraries, theatres, and art galleries—after a youth spent in the countryside. In his (impeccably illustrated) biography of Maddox, The Scandalous Eye, Silvano Levy quotes generously from conversations and correspondence with the artist. These insights from Maddox provide a context for Henry Reed's social life in Birmingham before the war: During that time, I began to explore the possibilities I discovered in collage which questioned the innocence of all images and the allusiveness of reality. Evenings were spent with in talk with Robert and John Melville, the poet Henry Reed, and Dorothy Baker. On Sundays, we would go to the Film Society and saw for the first time the works of Eisenstein, Cocteau, Pudovkin, Fritz Lang and others. Afterwards, we would talk either about the film or more imaginatively. (p. 45) Reed, of course, was raised in Erdington, and from 1932-1936 he was studying at the University of Birmingham. Robert Melville would later become the art critic for the New Statesman. His brother, John Melville, was an artist also interested in Surrealism, who had occasion to paint a rather more traditional portrait of Reed (popup window). Along with Emmy Bridgwater, William Gear, and Stuart Gilbert, this circle of artists became the Birmingham Group. But Maddox's group of friends and followers was not not limited to painters: The entourage included George Painter, Harry Browne and Philip Troutman, who were literary scholars; Cornelius Russell, an art historian at the university; his wife Jane; Dorothie Hewlett; Edward Lowbry [sic], a microbiologist and poet; Roy Knight, a modern languages academic who had unsuccessfully tried to teach Maddox some French; Dorothy Baker, a writer; and the poet Henry Reed, who, whenever the opportunity arose, would introduce his 'heterosexual friend Conroy Maddox'. (p. 98) Reed's openness (and humor) about his sexuality never ceases to surprise me. This litany of Birmingham's intellectual A-list will keep me busy for weeks, hunting the library stacks for biographies and collected letters, sliding my digitus secundus down the "R" pages of indexes, looking for references to Reed (is that why it's called the "index" finger?). George Painter, the Proust biographer, had attended secondary school with Reed (see previous post). My Granger's Index lists five poems of Edward Lowbury which appear in various anthologies. His poem on the Hiroshima bombing, "August 10th, 1945—The Day After," appears on the Salamander Oasis Trust website. Lowbury's Collected Poems was published in 1993 (Contemporary Review 263, no. 1535 (December 1993): 329-330). The two mentions of Dorothy Baker are especially intriguing, A severely limited preview of Levy's The Scandalous Eye: The Surrealism of Conroy Maddox is available from Google Books (the copyrighted images appear to be restricted). I have a library copy here beside me, and it's a beautiful, glossy-paged book. I'm astute enough (but only just) to detect the influence of Picasso, Magritte, and Dali in Maddox's work, but I fear I have been forever spoiled for his googly-eyed collages by the Spongmonkeys (Flash, audio, weird).

Old EdwardiansGeorge D. Painter, OBE, wrote the famous, standard biography of novelist Marcel Proust (London: Chatto & Windus, 1959-65), the first volume of which he dedicated "For Henry Reed." Reed would later would return this honor by dedicating his collection of radio plays, Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (London: BBC, 1971), to Painter. It's no coincidence that Reed chose to dedicate his book to Painter, considering that the Hilda Tablet plays concern a young, idealistic biographer researching a famous (infamous, it turns out) author. Reed had given up writing his own biography of Thomas Hardy, after years of impossible perfectionism.

Walter Allen was a critic and novelist, and was a close second in reviewing Reed's collection of poetry, A Map of Verona: Poems, in 1946 (The Listener's anonymous review was printed just two days earlier). Allen's own poetry appeared in The Penguin New Writing in the 1940s, later spent a stint as an editor of The New Statesman and Nation, and frequently chaired the 1960s BBC radio programme, "The Critics." What did these men have in common? What did they share in common with Henry Reed? All three were graduates of King Edward VI Grammar School, Aston, Birmingham. That Allen and Reed shared a Birmingham connection I already knew, but it was not until I happened upon Jim Perkins' extensive personal website that I discovered Painter had been there, as well. Mr. Perkins was a member of Aston's class of 1950, and he has an exhaustive section devoted to his love for KEGS Aston, including an "Alumni Achievements" page, which has brief sections on Reed, Painter, and Allen. Aston Old Edwardians, all. Mr. Perkins thoughtfully provides a database of graduates (in MS Works or Excel), with their dates of admission, "an alphabetical list of the 11,500+ lads who went to Aston between 1883 and 1997." This list pegs down the year of Reed's entrance to King Edward VI Grammar School as 1925, the same year that Painter was admitted. They were both 11 years old. (Allen was already there, since 1922.) I am deeply indebted to Mr. Perkins for these facts. Many of Reed's biographies mention that, after graduating from the University of Birmingham, he tried teaching for year, "at his old school." I e-mailed Mr. Perkins to thank him for all the information he provides, and he rather selflessly forwarded my curiousity on to his fellow Aston Old Edwardians. One gentleman was kind enough to drop me a brief note, which reveals: I remember being taught in an English class by Henry Reed in 1940/41 while at the school, which had been evacuated from Birmingham to Ashby [link mine] during WW2. I think he was teaching there for a short time before joining the army. We had classes in the Manor House [also mine] in the town which was also used as accomodation for some of the boys. I lived in Ashby for three years with a couple who had no children and was well treated. So, Reed was teaching in Ashby-de-la-Zouch in 1940 and 1941. If he was taught for seven years at King Edward VI, he would have matriculated to the University of Birmingham in 1932. The facts of which match perfectly with Stallworthy's introduction to the Collected Poems. Assuming Reed traveled to Italy for the first time after university in 1936, and again in 1939, we're left only with a troubling gap for the years 1937 and 1938, during which he had poems published in The Listener and New Statesman and Nation, and wrote at least one article for The Birmingham Post. Where was he writing from?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||