|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Bowen"

|

|

|

27.7.2024

|

Novelist and biographer of Elizabeth Bowen, Victoria Glendinning, continues to provide new details of how Henry Reed was perceived by his contemporaries, and his visit to Ireland in the spring of 1946. I have covered here, previously, how Reed spent two weeks at Bowen's Court, Elizabeth Bowen's ancestral home in County Cork. Now, in a recent collection of letters and diary entries by Bowen and her long-time lover, Charles Ritchie, Love's Civil War (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2008, with Judith Robertson), we are privileged to discover more about how Reed's visit came about.

Star-crossed and married to other people, some context for Bowen and Ritchie's relationship is provided on the collection's front flap:

The love affair between the writer Elizabeth Bowen and the elegant and charming Canadian diplomat Charles Ritchie blossomed quickly after their first meeting in 1941 and continued over the next three decades until Bowen's death in 1973. Theirs was a passion that flourished in the heightened, dangerous atmosphere of wartime London that Bowen wrote about so vividly in her novels. When Ritchie's diplomatic career took him further afield — to Paris, Bonn, New York and Ottawa — the lovers wrote to one another continuously, sharing their hopes and fears, their boundless affection for one another, and their longing to be together again. Published for the first time in this exquisite volume, accompanied by extracts from Ritchie's remarkably candid diaries, the love letters of Elizabeth Bowen reveal a passionate, intelligent, eloquent, strong-minded and wonderfully funny woman. They also reveal a man bewitched by her writer's mind and imagination, and by her adoring vision of him as a greater man than he ever felt himself to be.

More details about Bowen and Ritchie in this Guardian review.

Henry Reed and Michael Ramsbotham traveled to Ireland in the spring of 1946, to celebrate Ramsbotham's demobilization from military service. While it's unclear if they traveled separately, or if perhaps Ramsbotham was already in Ireland at the time, in Bowen's letter we find Reed alone in Dublin, when he inquired if he might pay a visit. Bowen was already aware of Reed, as he had reviewed her collection of short stories, The Demon Lover, for The New Statesman in November of 1945. Bowen wrote to Ritchie:

Bowen's Court, Kildorrey, Monday, 20th May 1946

My darling....

The world of letters has followed me here in the person of Henry Reed, one of those young men who write for the New Statesman. He was staying in Dublin and asked if he could come here. He is one of those fascinating homosexual characters, and a very good poet — has just published a book of poems called Map of Verona. He comes from Birmingham and is of lower-middle-class origin, but has romantic aristocratic views. His boy friend, a gentle creature whom I met in London, is lurking in some other part of Ireland, waiting about for him, so I said he had better come here too: they had had some notion of a tryst in Killarney, but Henry did not seem very enthusiastic about that, and as he evidently prefers to stop here I think he had better have his friend with him. He is very good company (I mean Henry) and does not interfere with me, as he regards it as essential that I should get on with my novel. So if the boy friend, who is at present preserving a moody silence, can be traced, they are to forgather here. I wish I had Anne-Marie's [Romanian Princess Callimachi, in exile] passion for intervening in masculine love affairs, but I haven't.[...] Love from E.

[p. 91]

So, Bowen was already acquainted with Ramsbotham, as well! And we see what might be construed as the beginnings of civil war in Reed's relationship with Ramsbotham, which would only last until 1950. At the time of this letter, Bowen was writing The Heat of the Day (London: Jonathan Cape, 1949), her novel on wartime London.

In addition to her work on Bowen, Victoria Glendinning has published biographies on Vita Sackville-West, Edith Sitwell, Jonathan Swift, Anthony Trollope, Rebecca West, and Leonard Woolf. Love's Civil War has just been re-released in paperback.

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

This review comes from the New Statesman and Nation for November 3, 1945 (p. 302-303). Reed devotes most of his time and effort to reviewing Bowen's The Demon Lover and Other Stories, which apparently he thoroughly enjoyed. Reed was friends with Bowen, and would later spend two weeks holiday with her at her ancestral home in Ireland in April, 1946 ( map).

New Fiction The Demon Lover. By Elizabeth Bowen Cape. 7s 6d

To the Boating. By Inez Holden Bodley Head. 7s 6d

First Impressions. By Isobel Strachey Cape. 7s 6d

It is not an accident that in her little book on the English novelists [English Novelists. London: William Collins, 1942] Miss Elizabeth Bowen should have written so well of Thomas Hardy and Henry James. Hardy, it will be remembered, thought poorly of The Reverberator, James not altogether well of Tess of the d'Urbervilles; and the two giants had little in common except their occasional dependence on a hard centre of melodrama—cruder, surprisingly enough, in James than in Hardy. Miss Bowen has something in common with both of them, though she manages to avoid their improbabilities, and she has enough of the true radiance of art to justify one's mentioning them. She shares Hardy's love of architectonics and of atmosphere: what Hardy will make of a woodland, heath, or starve-acre farm, she will make of a house or a summer night; and so far as persons go, I think the creator of Tess and Eustacia would have admired the drawing of Portia and Anna in Miss Bowen's The Death of the Heart. And she shares with Henry James a love of seeing how a story can be persuaded to present problems of artistry in the presentation of the "point of view"; and a curiosity (it is not the same as belief) about the supernatural and about the ambiguous territory between the supernatural and the natural. She has not James's sense of "the black and merciless things that are behind great possessions." Evil itself does not intrude on her world. It is not evil, but experience (they are not dissimilar, perhaps, but they are not the same) that corrodes the innocent people at the core of her books.

In her new collection of stories it is frequently obvious that she shares James's preoccupation with style; she has that kind of exact awareness of all she wishes to say, which makes her know precisely where a sentence needs to be a little distorted, or where an unusual word needs to be used. She has as well that gift which prose can share with poetry: the ability to concentrate the emotions of a scene, or a sequence of thoughts, or even a moral, into an unforgettable sentence or phrase with a beauty of expression extra to the sense:

The newly-arrived clock, chopping off each second to fall and perish, recalled how many seconds had gone to make up her years, how many of these had been either null or bitter, how many had been void before the void claimed them. Or again, about the present day:

He thought, with nothing left but our brute courage, we shall be nothing but brutes. Her short stories possess the qualities of her novels, but inevitably the atmosphere in her short stories is richer and more concentrated. The more elaborate of them suggest the climaxes of the elements of novels, but in a necessarily muted or diminished form; it is their atmosphere which moulds them, and which at times perhaps even brings them into existence. A perfect example of this is the first story in the book, "In the Square." Little happens in it, but enough strands are gathered together to give a sense of tension, climax and relief. And the relief is achieved mainly by atmospheric means. The story is about a few people living on in a partially bombed house in a ravaged London square. The principal feeling one has about them is their terrible independence of each other; all of them have mysterious, irregular relationships, unhappy and furtive. One has a feeling that what remains in the house, that reluctant proximity of the unconnected, is not what a house is meant to enclose. This is what war has done: to houses, to people. It is a true enough observation; but what startles one is the fact that one suddenly becomes aware that the early evening is spectacularly merging into late; the time of day is changing and a shift inthe emotions of all the characters is coinciding with this. A mere observation has become a story quivering with subtle, dramatic life.

The war, and the subtly degrading effect of the war, hold these stories together as a collection. They have a great variety and many attractions. One thinks particularly of their comedy and their dialogue; the story called "Careless Talk" is a brilliantly literal interpretation of that official phrase; "Mysterious Kôr" has a wonderful conversation draped round evocations from a poem by—Rider Haggard; the woman in "Ivy Gripped the Steps" is a strong enough figure for a novel. But it is probably those stories which involve the supernatural that are most striking. "The Demon Lover" itself, a ghost story of the traditional kind, is horrible enough, though not of Miss Bowen's best. In some of the others—"Pink May" and "The Inherited Clock," for example—the ghostliness is blown into existence by, or from, something real; and always, even when the boundary into the abnormal is passed, the normal still accompanies us.

The finest story in the book, and the most ambitious, is called "The Happy Autumn Fields." It begins in the past—perhaps seventy or eighty years ago. Various members of a large family are taking a late afternoon walk across the fields of their estate; at a moment of particularly painful emotion for one of the characters, Sarah, the story breaks off, and we are switched to the present: to a partly bombed house where a woman called Mary is waking from the scene we have just read about; it is not the first dream about the epoch she has had, though her real link with it is tenuous; nevertheless her dream has become obsessive, stronger and more attractive than her own life. The scene changes to the old family again, and we find that that afternoon in the fields Sarah had a black-out which has projected her for a moment into a world nameless and horrible—our own, we gather. The final scene is back in the bombed house, with Mary sorrowing over the irrecoverable day from the past which has blown into and out of her life:

I am left with a fragment torn out of a day, a day I don't even know where or when; and now how am I to help laying that like a pattern against the poor stuff of everything else?—Alternatively, I am a person drained by a dream. I cannot forget the climate of those hours. Or life at that pitch, eventful—not happy, no, but strung like a harp....' It is, like "The Turn of the Screw," a story which provokes interpretation and commentary; but since it is, in a serious sense, a discovery, there remains about it something of its own, at once inexplicable and profoundly satisfying. No living writer has, I think, produced a finer collection of stories than this.

Miss Inez Holden is well known for her skilful reporting of factory life. To the Boating is offered as a collection of short stories. But in most of them the bridge between reporting and art has not been crossed. in the first story, "Musical Chairman," there is an excellent account of a series of pathetic and amusing interviews between the Chairman of a Local Appeal Board and various people who are rebelling against the Essential Work Orders. But the fancy bits of stroy-telling in which Miss Holden has arbitrarily framed these scenes are so artificially stuck on that they have not been blown away in the proof-reading. It is a drab collection of oddments that Miss Holden has put together. And she shows, furthermore, a taste for drabness for its own sake. The book concludes with three fanciful little satires: presumably in order to deaden any excitement which these might arouse in the reader, Miss Holden has chosen to swathe them in the grey, vague mists of Basic English.

The habit, common enough in contemporary poets, of publishing work of an elementary or even infantile nature, is spreading to writers of fiction. Shown to one in manuscript, Miss Holden's stories and Mrs. Strachey's novel, First Impressions, might reveal promise; one would note passages of humour or observation. Why, then, does one pass over these when the books appear in print? Doubtless because the books challenge comparison with the early work of writers who seem to have tested themselves more rigorously and more critically before emerging into print. Amateurish is the deplorable word that one cannot avoid in mentioning Mrs. Strachey's novel. It is supposedly a satire on the leisured life of the Twenties. Possibly Mrs. Strachey has seen that life, but there is nothing in this rambling, unformed little book that could not have been got from many other social satire. Bad syntax and petty indecency are no substitute for the slickness of wit which some satirists achieve in their first books, and which it is hard for a satirist to do without. And the title of Mrs. Strachey's book goes no way to excuse its muddle.Henry Reed

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

I have surely spent too much time in the library today. But it has been time well spent. In preparation for traveling to the libraries at Duke University next month, I have been attempting to make a list of everything I need to complete my collection of Reed's writings, mostly book reviews and poems published in The Listener and New Statesman in the '30s and '40s. I've started with last year's Most Wanted poster, crossing off anything I've since managed to obtain. Progress has been slow, apparently.

Sitting here in the icy-cold undergraduate library, however, I noticed there were at least two items on my list within cat-swinging distance. One was a 1948 book review of The New British Poets, which only mentions Reed lumped along with Patrick Evans, G.S. Fraser, Wrey Gardiner, Sean Jennett, Vernon Watkins, and Laurie Lee. (Also, I may be the only person in town who actually bothers to pay for their microfilm photocopies, judging by the poor, flustered students working the Circulation Desk.)

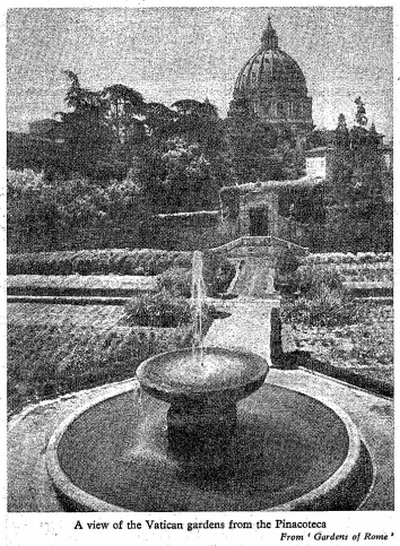

The second, however, was a review of Elizabeth Bowen's A Time in Rome (1960), critiqued by the consummate Italophile himself, Henry Reed.

The photograph above is from Gardens of Rome, by Gabriel Faure (1960). Here's a more recent shot (Flickr) from (almost) the same perspective. The "Pinacoteca" is the Vatican art museum.

The review appears in The Listener from January 12, 1961, and is entitled " Rome: 'Time's Central City'" (.pdf). Reed seems to have thoroughly enjoyed it. He may have been slightly biased owing to his friendship with Bowen, but when it came to Italy, I don't believe Reed would have pulled any punches. When have you ever seen such dexterity with a semi-colon?

[A Time in Rome] is the exact antithesis of most travel books. It is magnificently unillustrated, for one thing; for another, its author is explicitly anxious not to be of help to any other visitor. It is essentially a book to be read away from Rome, not in it. It has further negative virtues; there is nothing about the unremitting winsomeness of the natives; there are none of those maudlin conversation-pieces with which even the sincerest are wont to bedizen their reminiscences; and none of the authoritative inclusiveness of the dug-in expatriate ('Gino smiled, as no one outside Florence knows how to smile: and all Florentines of course have perfect teeth'). Miss Bowen sees selectively, and with adequate passion; she is not an indiscriminate watcher; she is not a camera (nor, in point of fact, was Mr. Isherwood). If she tells you anything about Rome, she gives you a recognizable part of herself with it...[.]

'Gradually,' Reed says later, 'one begins to see that this book, like all Miss Bowen's work, is about a form of love.' At no point does he take to task any of Bowen's ideas or findings about Rome. Indeed, her Rome, he says, 'is perfectly created, and separate now from the city itself.'

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

I reached a minor milestone this past weekend: I closeted myself in the library, and labeled and stuffed nearly 150 manila envelopes with the last of the photocopies from the original plastic filebox, as well as most of the printouts and copies I've made since making the decision to go Noguchi. Now, all I need to do is spend four or five hours double-checking that all the items in these envelopes are actually in the bibliography, and then I can file them in the bookcase. Progress! The tide is turning.

But no matter how much I file away, new items are still emerging, including this fascinating item. In Victoria Glendenning's biography of Elizabeth Bowen (New York: Knopf, 1978), there is this possibly scandalous revelation:

As to reviewing, which she always did a great deal of, she was ambivalent. She was a notoriously kind reviewer of novels; she preferred not to write about a book she could not praise, and was known in the business as a very soft touch. But "it is a perfectly awful business", she wrote to Virginia Woolf about The New Statesman fiction-reviewing stint she was doing in 1935, alternating weekly with Peter Quennell. Once when Henry Reed was staying at Bowen's Court and she was very involved with her own work, "Henry even did some of my Tatler reviews for me, which left me more time for the novel: a friendly act". It was indeed. (p. 146.)

I was flabbergasted. I read it again: Henry Reed wrote some of Elizabeth Bowen's book reviews for her.

Elizabeth Bowen began writing for The Tatler in 1938. In 1940 the journal merged to become the monthly Tatler & Bystander, and from 1945 to 1958 Bowen was reviewing fiction regularly, in her "Book Shelf" column.

Stallworthy mentions that Reed spent a fortnight holiday in April, 1946 at Bowen's Court, Elizabeth's ancestral summer home in County Cork, Ireland. Would this be the visit when he did her Tatler reviews for her? Which novel was she working on? Was it The Heat of the Day, her only work of long fiction published between 1938 and 1949? Also, the quote about Reed is apparently unattributed: it can't be part of the preceding letter to Virginia Woolf, because Woolf committed suicide in 1941.

I am at an impasse, however, because there is no run of 1940s Tatler & Bystander even remotely accessible, and there is no available index. Some hope may lie in a 1981 bibliography of Bowen's work (by Sellery and Harris), but according to the introduction of The Mulberry Tree: Writings of Elizabeth Bowen (Lee, 1986), 'there are almost seven hundred entries under the section that includes reviews.' That's daunting, even if I'm only looking at the mid-Forties Tatlers.

But the Big Question is: did Reed write Bowen's Tatler book reviews under his own byline, or hers? Is it possible? Are there Bowen-attributed Henry Reed blurbs littering the advertisements of literary journals from 1946? Or simply un-indexed Reed reviews waiting to be re-read?

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|