|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "NewStatesman"

|

|

|

26.7.2024

|

Here we find a letter from Evelyn Waugh to the novelist Nancy Mitford, written in 1946, regarding a review in the New Statesman and Nation by Henry Reed, of Mitford's novel, The Pursuit of Love.

Waugh is "irritated" by Reed's review, and by newspapers and journals and news, in general. Waugh doesn't know who Reed is, and even seems to think the byline on the review is a pseudonym (this despite Reed having reviewed Brideshead Revisited just the year previous). Waugh does somehow infer Reed's homosexuality on the basis of his review, but mistakes him for a lesbian.

This from the The Letters of Evelyn Waugh, edited by Mark Amory (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980), pp. 222-223: Piers Court. To NANCY MITFORD

4 February 1946

Dearest Nancy,

Since sending you a post-card today I purchased the New Statesman. I thought 'Reeds'1 review of your book egregiously silly both in praise & blame. I love all the Mitford childhood, as you know, but to single out the buffoon father while totally ignoring the unique children's underground movement is brutish. He calls your one false character 'a brilliant sketch'2. You know better than I how wrong he is about Fabrice. The review irritated me greatly. I wonder who it is who writes it. Plainly a homosexual; perhaps a Lesbian?

I looked at other pages of the paper & was astounded that you take it in. I read Eddie [Sackville-West] describing the use of the word 'brothel' on the wireless as 'a refreshing experience which spoke eloquently of the intelligence, sanity and good feeling of ordinary people'. I read 'Nothing can stop big Powers bullying their small neighbours if they wish to do so'. Last time I had the paper in the house it was boiling to attack Germany & Italy for no other reason. I read the wild beast saying that Mr Sutherland's painting 'rivals butterflies wings in delicacy.'3

The only thing that made any sense in the paper was a grovelling apology to a soldier they had insulted, but that had been dictated, presumably, by some intelligent solicitor.

How can you read it? It explains all that modern trash that encumbers your shop.Evelyn

1 Henry Reed (1914- ). Poet and BBC producer.

2 Talbot, the middle-class communist in The Pursuit of Love.

3 Raymond Mortimer was reviewing The Approach to Painting by Thomas Bodkin.

Here is the irritating review, from the New Statesman for February 2, 1946. Reed invokes several lessons from Joyce, including the best description of synecdoche ever written: "When a part so ptee does duty for the holos we soon grow to use of an allforabit."

NEW NOVELS

The Pursuit of Love. By Nancy Mitford, Hamish Hamilton. 8s. 6d.

Of Many Men. By James Aldridge. Michael Joseph. 8s. 6d.

The Crater's Edge. By Stephen Bagnall. Hamish Hamilton. 6s.

Everybody will remember that encouraging moment on page 108 of Finnigans Wake when, into the sleeping mind of H. C. Earwicker, as he toils over the difficulties of Anna's elusive letter, there flow these calming words: "Now, patience; and remember patience is the great thing, and above all things else we must avoid anything like being or becoming out of patience. A good plan used by worried business folk ... is to think of all the sinking fund of patience possessed in their conjoint names by both brothers Bruce ..." They are words I have often used to prop, in these bad days, my mind, as in my turn I have toiled through the pages of recent fiction. Patience is needed with all of the books listed above, even with Miss Mitford's The Pursuit of Love, which is rewardingly funny in many places. This is the least, and indeed the most, one can say of it. It begins extremely well with a picture of the children of an aristocratic family called Ratlett. Its early pages introduce, in Uncle Matthew and Captain Warbeck, two of the best comic figures in any modern novel, I cannot recall a funnier picture of the violent foreigner-hating patriarch than Uncle Matthew; his early morning foibles are beautifully recorded:He raged around the house, clanking cups of tea, shouting at his dogs, roaring at the housemaids, cracking the stock whips which he had brought back from Canada on the lawn with a noise greater than gun-fire, and all to the accompaniment of Galli Curci on his gramophone, an abnormally loud one with an enormous horn, through which would be shrieked "Una voce poco fa"—"The Mad-Song" from Lucia—"Lo, here the gen-tel lar-ha-hark"—and so on; played at top speed, thus rendering them even higher and more screeching than they ought to be.

... the spell was broken when he went all the way to Liverpool to hear. Galli Curci in person. The disillusionment caused by her appearance was so great that the records remained ever after silent, and were replaced by the deepest bass voices that money could buy. But, alas, though Uncle Matthew dodges in and out of the whole book, the later pages are given over to the affairs of one of his daughters; Linda. It is to her that title refers. The less successful episodes in her pursuit—her marriages with the banker Kroesig, and with Talbot, the middle-class Communist (a brilliant sketch)—are convincing enough; but at a moment of despair she is picked up by a French duke and installed as his mistress, and thenceforward the novel has the sentimental staginess of the late W. J. Locke. It has a certain characteristic contemporary wistfulness in its English admiration for the high-handed way in which upper-class French Catholics are presumed to fornicate, and one is interested to learn that the French are surprised if a woman does not express honte after a night with a lover. But it has also a dreadfully soft centre, and one is not surprised that Fabrice should eventually discover that what he feels for his enslaved mistress is the real right thing. They have both become unbelievable by the time Miss Mitford finally polishes them off; and in the later pages the irruptions of Uncle Matthew preparing to hold his house against the German invasion are a great relief:"I reckon," Uncle Matthew would say proudly, "that we shall be able to stop them for two hours—possibly three—before we are all killed. Not bad for such a little place." Of Many Men and The Crater's Edge each exemplify an extreme of mannerism which we may expect in war-fiction for many years to come. Of Many Men is the extremely hard-boiled type of war-novel, The Crater's Edge the extremely soft-boiled type. This is nowhere better illustrated than in the prose style of the two writers; in offering for the reader's judgment a little example of each, I am reminded of yet another of Joyce's persuasive remarks: "When a part so ptee does duty for the holos we soon grow to use of an allforabit." Here, for instance, is a characteristic passage from Mr. Aldridge:Wolfe entered Damascus with the French. The day after they arrived the Germans invaded Russia. Wolfe got the first Nairn bus that went to Baghdad and then he flew over the dead mountains to Teheran.

The Russians in Teheran said they were sorry that Wolfe had been in Finland, very sorry; but if he waited maybe he would get a visa. He waited a long time and the Red Army was still retreating to the Dnieper when he left Teheran. He could not get a visa.

The Germans were also in the Western Desert now. They had pushed the British back in to Egypt and had encircled and isolated the Australians at Tobruk. Wolfe went into Tobruk on one of the relief boats. And here we have Mr. Bagnall:If a girl loves someone at the age of sixteen for whom she has protested the madness of her love as a child of eight, even then he cannot be sure of her constancy, because, since nothing came of that protestation, nothing has flowered, and therefore nothing has had an opportunity to either flourish or die. Rather it has been in a state of perennial bud. So at first he made a noble decision of renunciation. Or perhaps it was not so much a decision he made as an attitude that he struck. Because he knew all the time he would not remain faithful to it. Yet he held it long enough to crystallise, or perhaps embalm, it in a sonnet of great-hearted finality and generous resolve. Generous himself at this point, Mr. Bagnall spares us the sonnet; but he spares us little else. His theme is one of those old, well-tried ones, which were never any good even when new: the theme of the dying man reliving the past. Not even vivid interludes can remove the distrust one has for a story whose end is also its beginning; and Mr. Bagnall's story has no vivid interludes. It is merely a series of lush reminiscences about the hero's four loves: his love for a ballet dancer (platonic), for a schooldays' friend ("without lust"), for a girl called Celia (with), and youthful Elizabeth (the real right thing once more) With its juicy, self-admiring prose, its purple passages, its recklessly misrelated participles and its lengthy commonplaces about the major problems of life, it is not an easy book to read.

The point of Mr. Aldridge's book lies quotation which prefaces it: "War is the shape of many men, those in the sun and those the shade; many hands clear the shade, but in truth they have only succeeded when the last shadow is gone." The book begins with its hero, emerging from the Civil War in Spain; during the next few years, in an unspecified capacity, he tours the second world war in Finland, Norway, Syria, Africa, Malaya, the Pacific, Italy and Germany; the facility with which he gets about will be seen in the passage I have quoted. After VE Day he announces his intention of returning to Spain, and the point of the book is made clear. Presumably if Mr. Aldridge had waited a month or two longer, we could have accompanied his hero to the bombing of Hiroshima (doubtless inside the actual aircraft) and to the meetings of Hirohito and MacArthur. The pity is that even when we have had the overwhelming course to accept Mr. Aldridge's style as a means of communication, he appears to have nothing to communicate beyond his central statement; the scenes we visit as we fly from one battle-front to another are stupefyingly machine-made. And though none will doubt the the truth of his epigraph, and few will doubt its application to Spain, it is a pretty bald gag to write a book about.Henry Reed

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

I was recently led by a database — and ultimately disappointed — to an issue of Vogue in 1948 containing reference to Reed. It was in an article on the Sitwell dynasty: Edith, Sacheverell, and Osbert Sitwell. The article, which appeared in the November 15 issue, " The Importance of Being the Sitwells," has a layout of paintings and photographs, while the text consists of pullquotes and anecdotes concerning the trio (mostly Dame Edith, let's be honest) from a myriad of sources. Reed's paragraphs (on the last page), are sourced as being from Denys Val Baker's 1946 anthology Writers of Today; but ultimately that's just a reprint of his 1944 article from Penguin New Writing, " The Poetry of Edith Sitwell."

Osbert Sitwell was a huge influence on Reed's development as a poet and writer: he brought Reed under his wing introduced the young poet to what must have previously seemed like an unreachable circle of writers and musicians, actors and artists. Sitwell was chairman of the Society of Authors when Reed was given a bursary to support his writing in 1945: £200 per year for three years. Reed lunched with Edith Sitwell in London at Osbert's urging; Osbert sent Reed to visit Violet Gordon-Woodhouse during the Blitz.

Reed reviewed the second volume of Osbert's autobiography, The Scarlet Tree, for The New Statesman and Nation on August 31, 1946. A self-proclaimed Kleinian, the memoir probably helped cinch Reed's views on the influence of childhood on the authors and novels of the mid-twentieth century. Reed devotes a full page to Sitwell:

BOOKS IN GENERAL The Scarlet Tree, by Osbert Sitwell (Macmillan, 15s.) has an advantage over many autobiographies: it is written by an experienced novelist, who is here turning into art a richer material than he has used elsewhere, and who is partly employing the novelist's craft in shaping it. Who else but a novelist could contrive the checks upon racing Time which we find in this book, the disposition of a heavy emphasis here, a light one there, the holding back of an explanation till "later," the anticipations, the use of suspense, and above all the carefully-timed entrances and re-entrances of the characters? In biography Sir Osbert Sitwell's contrivances would be intolerable; in autobiography they are a blessing: There is something else which strikes one as one compares this book with a novel: because this is life, and not fiction, certain characters with traits which would in a novel be unacceptable outside the broadest farce are acceptable here. Where, in a novel, after our acquaintance with a character, has extended over several hundred pages, could we believe the, statement that he had "invented a musical toothbrush The Scarlet Tree which played 'Annie Laurie' as you brushed your teeth, and a small revolver for shooting wasps?" Sir George Sitwell, the author's father, is said to have invented both of these; perhaps they worked; but we should be rather incensed by the idea in a novel. So that, throughout, The Scarlet Tree has all the virtues of a large-scale discursive roman fleuve, with none of the restrictions of probability that a serious novelist has to impose on himself.

There is plenty to make the reader laugh in this autobiography; there are many exquisite comic miniatures where absurdities are highly packed into a small space, as in the account of two of the author's elder cousins:

But, in fact, they got on well together, in spite of their differing so often in the opinions they put forward. In the past, however, certain disputes had taken place occasionally, so that each sister has pasted somewhere on every article of furniture belonging to her — whether it were an oak chair, a table, a bronze, a chased-silver photograph-frame, or merely a Japanese vase full of last year's pampas-grass — a label, which bore on it in clear, black, decisive letters, admitting of no question, the name FLORA or FREDERICA. Thus, if either of them decided of a sudden to quit, she could accomplish it immediately, departing with her own belongings and without the possibility of further discord. But in its major intention The Scarlet Tree is a tragic, not a comic, book. Things which were treated comically, or hinted at in a non-committal tone neither of comedy nor of tragedy, in Left Hand, Right Hand, begin to develop more darkly here. And yet it is part of the novelist's art that the most lingering impression of the book is a quality not of darkness but of light. Indeed, descriptions of light are part of its scheme: Were is along Proustian meditation by the author while, as a child, he lies in bed at daybreak and feels the day increasing behind the shutters; there is another, a little later in life under the title of A Brief Escape into the Early Morning. Yet bathed in light though the book is — and one wishes that Mr. Piper's pictures had turned occasionally aside from their excruciating melodramatic gloom to try and recapture a little of this — the book is principally a picture of tragic childhood, of infant vitality, exuberance and perspicaciousness flickering against deepening shadows of older futility. If, in fact, one or other of this distinguished family of writers has sometimes seemed, in print, a little too easily indignant or provoked; if they have had less difference to the censure which all writers of genius sometimes evoke than their admirers would like to see in them: then perhaps we find the reasons in The Scarlet Tree. But while the author employs much candour in speaking of his upbringing, he leaves it to his readers to make, if they choose, explicit comment on it. A critic may perhaps be allowed to describe it as horrible and appalling. No one can contemplate without misgiving those pathetically awful small children who are allowed a wholly uninhibited expression of their impulses, and who early realise with the natural cunning of children that there are no limits to how far they can go. But the opposite of this is scarcely better: the children rigorously subjected to the sort of well-meant cruelty — a complete divorce of ends and means — which permitted Sir George Sitwell always to insist that his children should do the exact opposite of anything they showed pleasurable inclination towards.

Yet it is not to be imagined that Sir Osbert presents his father in the familiar guise of an Edward Moulton-Barrett [father of Elizabeth Barrett-Browning]. The most subtle and original thing in this book is the suggestion it gives that all early development is haphazardly circumstanced: it is a crawl through a garden wilderness where the cruellest briars and the largest fallen branches which impede the way pave also once had their struggles for existence and growth. It is a wise sense of this that persuades, Sir Osbert in talking of his own upbringing to open out for us a remoter vista: the childhood of his father.

Here, having watched the development of a character, as seen by a child, a son, the reader may ask why my father so continually insisted on being in the right, to the extent that if events proved to him that he had been wrong, and he could no longer avoid such a conclusion, he had to fall ill... The reason, I deduce, must be sought a long way back, in the 'sixties of the previous century when he was a small child... I used to think that his disposition and his whims, sometimes so delightful and removed from reality, at others so harsh, and, indeed, hateful, were the result of his having been brought up entirely by women since the age of two, when, as we have seen, he succeeded his father; were rooted in the circumstance that he had never been controlled or disciplined or contradicted, and that, further, he had inherited an ample fortune at the age of twenty-one, finding himself, in fact, one of those local princes of whom Meredith tells us in The Ordeal of Richard Feverel. But my father had always maintained that his mother, though, by the time I knew her, gentle and on occasion almost indulgent, had not — for she was one of a family of five daughters — understood how a boy should be managed, and had treated him — of course without meaning to do so, for she was utterly devoted to him — with severity, and sometimes almost with cruelty.... And I have come to believe that this was true since I found in 1938 in the library at Renishaw a forbidding-looking account-book, short and thick, with an ecclesiastical clasp of brass. I opened this volume at random, and my eye lit on a page, not devoted to figures, on which were written, in a round, childish hand, very different from that which I knew, and yet even then recognisable, the words "George naughty again Jan. 20th." From the character of the letters, he plainly could not have been more than six or seven when obliged to enter that sentence. Underneath was inscribed in my grandmother's beautiful, flowing hand, "George naughty a second time Jan. 20th." There are many variations in the book on the theme of semi-conscious paternal bullying; and there is a good deal of its painful counterpart, semi-conscious maternal indifference. Lady Ida Sitwell could also be cruel — and in a perhaps more despicable way — but a part of her was all on the side of kindness, and it seems to have been easily played on by the unscrupulous; but the actions of her life, according to the testimony of a son whose completely affectionate attitude to her cannot be questioned, were principally dedicated to the pursuit of "fun"; and to such a temperament as hers, children provide little. Where it was most craved, therefore, her kindness was something least forthcoming. Yet there is an element of "attack" in Sir Osbert's account of his upbringing, though some things — among them his mother's attitude to his sister — cannot be treated with complete equanimity; but about his own injuries he has come to that state of comparative calm (it is nothing so smug as forgiveness, which: is always rather an indecent gesture on the part of a human being) the attainment of which is part of every artist's task.

This volume covers ten years of the young Osbert's life. It includes the deepening of certain threatening shadows at home, the whole of his school life, accounts of London and Scarborough, and his first glimpses of Italy. On its more sombre side it includes, too painfully for isolated quotation, a brief, horrifying scene with an unscrupulous private tutor, one of those dramatic moments of suspense and foreboding which are again, a hint of the art of the novelist — points of significant detail which crystallise a whole phase of life. The accounts of the schools — a day, school at Scarborough, two private boarding-schools, and Eton — are written not without ferocity. But there is more than that: we are used to people writing satirical, indignant or regretful accounts of their schooldays; with rare exceptions, there seems to be little reason for them to write otherwise. Sir Osbert employs satire and indignation — Bloodsworth in particular, appears not to have been far short of a torture-chamber — but he sees deeper than, these instruments by themselves will allow a man to see: he uncovers a process of malformation, permanent or temporary. Esce di man di Lui l'anima semplicetta; but, the simple little soul returns from his second world severely misshapen:

The school restored to my parents a different boy, unrecognisable, with no pride in his appearance, no ability to concentrate, with health impaired for many years, if not for life, secretive, with no love of books, and an impartial hatred for both work and games, with few qualities left and none acquired, save a love of solitude and a cynical disbelief, firmly established, in any sense of fair play or prevailing standard, of human conduct. He has no hesitation — why should he have? — in making clear who or what helped to undo this mischief. Principally, himself; but some things in addition which were denied to many of his companions. There was the calm beauty of Renishaw; there were his own growing apprehensions of the things man has formed out of the mess of life; there was Italy. It is a tempting preciosity to say that the Englishman's education and sensibility are incomplete without Mediterranean experience. It is also a palpable falsity; they are equally incomplete without experience of the South Seas, China, Russia and India. But to the English artist (to say nothing of anyone else) Italy has a strange power of benediction — more potent and residual perhaps when no attempt is made by the Englishman to externalise, its beauty into art; Sir Osbert is not, of course, the Englishman Italianate who incurred and deserved Elizabethan censure; but now that the centre of diabolism seems temporarily to have moved to Paris, it is delicious to find the magic of Italy restored in pages that are among the best in the book.

The remarkable achievement of The Scarlet Tree is its avoidance of an episodic character. No writer of our time — unless perhaps Mr. William Plomer in his own autobiography — has shown greater delight in the unusual and absurd sideshows of human behaviour, or more tenacity in storing them up, for future reference. But in The Scarlet Tree anecdotes are used only as occasional illustration to the general succession of the "movements" of life. It is not a book which over-emphasises detail at the expense of form: the whole work, of which this is said to be a quarter (though one prefers to hope that it will be but an eighth or a twelfth) promises to be a masterpiece of controlled expansiveness; it has already a quality of humorous and urbane magnificence, and a romantic lyricism rare in contemporary prose. It is worth while remembering that this is achieved in spite of rather than because of the author's native background. Our times provide us with a new opportunity for snobbism which we eagerly grasp at; with a gracious smile we accept socialism, and with a wider one we indicate how much we are giving up. The author of The Scarlet Tree knows all this; and he is at pains to show in these Edwardian chapters what sterile dramas could enact themselves, what futile games be played, against the background of Renishaw. He insists that the notable qualities of himself, and of his brother and sister, are qualities of mind. These they brought with them; they did not find them there.

Henry Reed Who could read all that and not put both Left Hand, Right Hand and The Scarlet Tree on their wishlist?

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

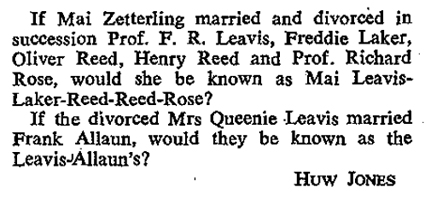

Here's a nice little piece of pop culture, which is not only a good laugh, but a good gauge of where Reed stood in the public eye in his later life. The New Statesman's reader competition for June 22, 1973:

Weekend Competition No 2,261

Set by Young Werther

To revert to an old joke-form ('If Lee Marvin married the Princess Lee Radziwill would he be known as Lee Marvin-Lee Radziwill?'), it would be intriguing to know whether, if Beatrice Webb had been around to marry Michael Foot, she would be known as Beatrice Webb-Foot, or if Grace Wyndham Goldie had married D. B. Wyndham-Lewis, she would have been known as Grace Wyndham-Goldie-Wyndham-Lewis. Competitors are asked to supply up to five such examples. Entries by 3 July. (Real names only) And the results, published on July 13: Result of No 2,261

Report by Old Goethe

The same couples came up with surprising and rather disappointing frequency. Too many Brown-Windsors, with only John Fuller providing a plausible explanation; too many Virginia Woolfs and J. M. Whistlers, Grace Darlings and W. G. Graces, Billie Jean Kings and Bobby Fischers, and nothing quite on par with the legendary match between Tuesday Weld and Frederic March's eldest boy (she'd have been Tuesday March 2nd). Under the circumstances, it seemed sensible to bend the rules somewhat. £1 for each of those printed. Those printed included: If Maude Gonne could have married Richard West, would she have been known as Maude Gonne-West?

Brenda Rudolf

If Ellen Terry could have married Dylan Thomas, would she have been known as Ellen Terry-Thomas?

If Margaret Drabble married Sir Leonard Gribble, would she be known as Lady Margaret Drabble-Gribble?

Jedediah Barrow

If Gladys Hay married Ronald Biggs, divorced him and married Stephen Spender, would she be known as as Gladys Hay Biggs Spender?

Lee Woods

If the future Mrs Bernard Levin married W. H. Auden after her divorce, and after that divorce married Sir Alfred Ayer, would she be known as Lady Levin-Auden-Ayer?

Arabella Wittgenstein And the entry which caught our attention: If Mai Zetterling married and divorced in succession Prof. F. R. Leavis, Freddie Laker, Oliver Reed, Henry Reed, and Prof. Richard Rose, would she be known as Mai Leavis-Laker-Reed-Reed-Rose?

Huw Jones

Mai Zetterling was a Swedish-born actress; F.R. Leavis was, of course, a distinguished literary critic; Frederick Laker was an airline entrepreneur; Oliver Reed played Athos in The Three Musketeers and should need no introduction; and Richard Rose is an American political scientist who has taught primarily in the UK, and has a CV as long as my arm. The pun is a play on Burns, and I had to sound it out, twice.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

This evening, I'm reading Reed's old "Radio Notes" columns from the New Statesman, scanning for any personal information he might have let drop, in passing: vital clues to his haunts and hangouts, friends and visits, or activities. Here, for example, on October 25th, 1947, we learn he has been to see the controversial "Exhibition of Cleaned Pictures" at the National Gallery ("I wish that he [the director, Philip Hendy] could be allowed to appeal for funds which might help in getting the muck off some of the others"). On December 20th, Reed reports having recently attended a performance of Carrisimi's "most dramatic and beautiful work," the oratorio Jefte (at the Umbria Sacred Music Festival, possibly, in Perugia, Italy, the previous September?).

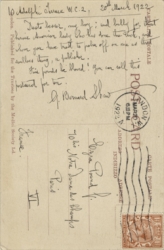

Then, in this last paragraph of the column for January 24th, 1948, there appears a paramount of name-dropping, blandishment, and cleverly phrased self-congratulation:

Second Opinion, discreetly and amiably presented by Mr. Frank Birch, has made an excellent and entertaining beginning. The proceedings opened with a postcard from Mr. Bernard Shaw about a discussion of Paradise Lost in which I had myself been privileged to take part. Modesty restrains me from divulging on whose side Mr. Shaw seemed to have been; what genuinely moved me was the thought that one's own humble mumblings had reached those ears at all. I have felt no comparable emotion since I gave up prayer. [p. 70]

Between October and December of 1947, the BBC's Third Programme broadcast an eleven-part dramatization of Paradise Lost, produced by Douglas Cleverdon, who cast Dylan Thomas in the role of Lucifer. The program was not well-received, and reviewing it for his December 6th "Radio Notes" (.pdf), Reed was forced to invent the term "inauscultable" to adequately describe his disappointment:

New arts demand new words, and in its short day the radio has given us many, not always beautiful. Seeking during the last few weeks to compound a necessary word that should be at once inoffensive in sound, clear in meaning and traditional in formation, I have met with a philological difficulty. The transitive Latin verb auscultme, to listen to, hearken to, give ear to, produces in English the two verbs 'to auscult' ( rare) and 'to auscultate,' the latter being familiar in medicine. Normally I would not wish to have truck with such words; the wireless I would either listen to, or switch off. It was some such word as inauscultable or inauscultatable that I wanted. After careful consideration of the rival claims of medicine and radio, I venture to suggest that inauscultatable be reserved for those organs inaudible even to the stethoscope, and that inauscultable be dedicated to such radio-programmes as Paradise Lost, which has now been going on for seven weeks, and has been more or less unlistenable-to from the very start. [p. 449]

Thomas's performance was a particular sore spot: "Week after week," Reed says, "we have had the voice of Dylan Thomas coming up like thunder on the road to Mandalay; rarely can such gusty intakes of breath have passed across the ether."

The new series which received a postcard from George Bernard Shaw, Second Opinion, was a show of audio letters-to-the-editor, consisting of correspondence from listeners concerning the Third Programme's talk and discussion programming. Following shortly after the final chapter, Reed participated in "An Argument on 'Paradise Lost'," broadcast Sunday evening, January 4th, 1948, which must have been something of an airing of grievances. It sounds as if Reed found, in Shaw's response to the conversation, more than ample vindication for his negative review. You can almost hear him patting himself on the back! I wonder where that postcard is, today. Buried deep in the BBC Archive?

Curiously, the humble postcard seems to have been one of Shaw's preferred methods of communication (Brown University Library exhibit), and he even had personalized cards printed, some with statements of his frequently requested views on such subjects as capital punishment, vegetarianism, and his failure to garner support for a new, 42-character, British alphabet (bottom of this page). Here's a postcard from Shaw to Ezra Pound in 1922, concerning the publication of Joyce's Ulysses (at Indiana University's Lilly Library):

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

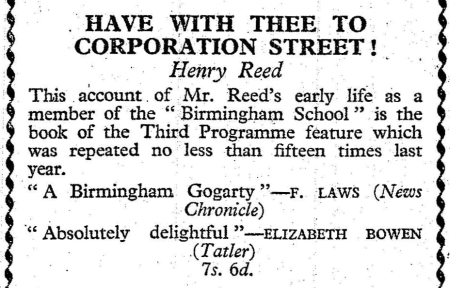

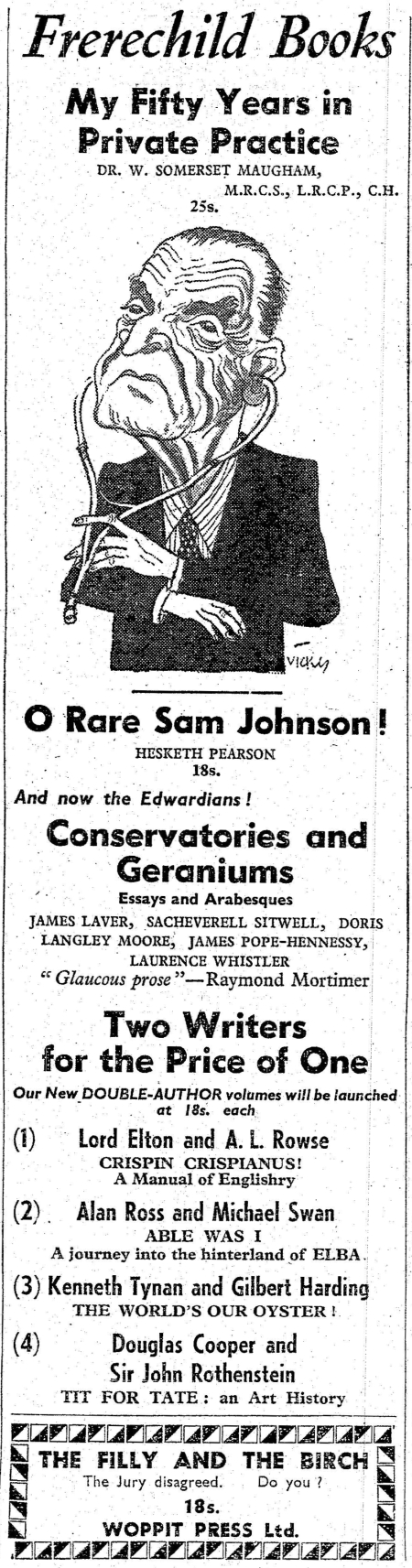

At first, I thought this was going to be a discovery of epic proportions, like a photograph of some exotic species, long thought extinct, or the finding a previously unknown, unexpected comet. Of course, it turned out that I was simply taken in—made the butt of a fifty-year-old joke. What first appeared to be an entirely unheard-of, obscure book written by Henry Reed, turns out to be merely a spoof advertisement for a non-existent, unwritten book: Have with Thee to Corporation Street!, complete with manufactured blurbs from critical reviews:

The ad appears in a two-page spread of the December 25, 1954 issue of The New Statesman and Nation, part of section called "Christmas Diversions." This elaborate hoax by the editors is entitled "Publishers Anonymous," and it's laid out to appear exactly like publisher's advertisements for new books by frequent contributors, being released specially for the Christmas holiday. It only takes the reader a moment to realize they're being had, but that's all that would have been required to grab their attention and get them to read the entire feature. Follow the linked image to my Flickr set to see the whole thing, with close-ups, and explanatory notes for some of the more obscure inside jokes (I'm lucky if I understand half of them):

There's a running gag where all of Elizabeth Bowen's reviews for The Tatler proclaim the books are "Absolutely delightful!" (Bowen preferred not to give negative reviews, and only reviewed work that she enjoyed), except for a book on critical reviewing, which Bowen finds "Instructive!"

The invented publishing houses include: Bourne & Griffin, Fathom House, Hussif Publications, Ivy and Fitzroy, Parlour Press, and Wildenstein & Pargiter, with this jape about Cyril Connolly, editor of the journal Horizon:

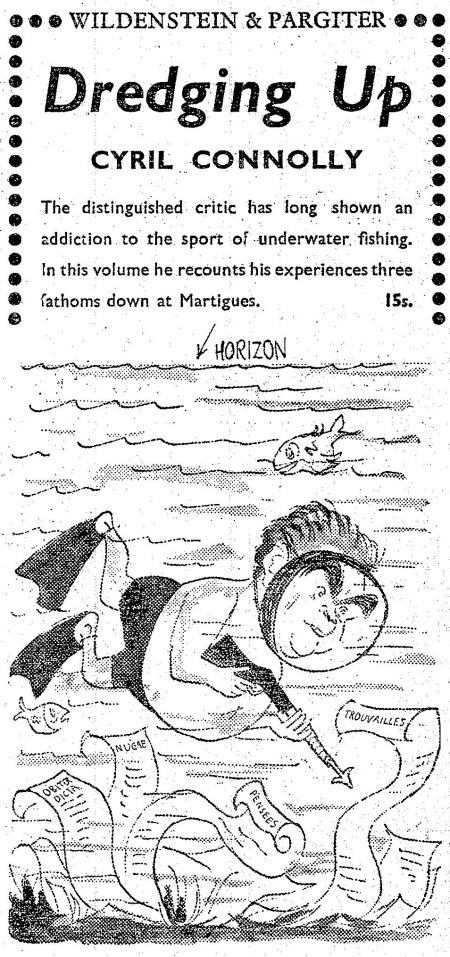

Then there's this delightful send-up of W. Somerset Maugham, who studied medicine before becoming a novelist, from "Frerechild Books":

The caricature was drawn by Victor "Vicky" Weisz, seen here at the British Cartoon Archive. Here's the entirety of the New Statesman's " Publishers Anonymous," scanned into a .pdf.

Even though it turned out to be all in jest, and I practically made a fool of myself, finding these pages is still significant. Reed was thought well enough of to be incorporated into the joke, which is certainly flattering. His inclusion places Reed among his friends and contemporaries, like John Betjeman, Elizabeth Bowen, Edward Sackville-West, and Angus Wilson. Reed's radio plays were apparently considered so popular they were replayed with almost ridiculous frequency. The comparison with Gogarty means that Reed was renowned as a wit of nearly Olympian proportions. And most importantly, the title of Reed's book secures him as a member of a group of writers and artists who frequently met at a pub off Corporation Street, Birmingham, in the 1930s: the Birmingham Group.

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

Henry Reed was the radio critic for the New Statesman and Nation for five months, writing the "Radio Notes" column for the Arts and Entertainment section. Between October, 1947, and February, 1948, Reed's byline appears after seventeen reviews of various music programs, interviews, debates, speeches, and plays.

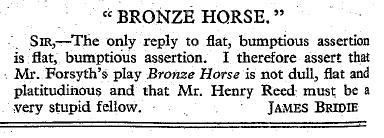

One such review resulted in a letter to the editor from none other than James Bridie, the Scottish playwright and screenwriter. Among his many film credits, Bridie worked on the scripts for no fewer than three films with Alfred Hitchcock, including The Paradine Case, in 1947.

In his January 31, 1948 "Radio Notes" column, Reed comments on an adaptation of The Bronze Horse, recorded previously and broadcast on Friday, January 16, on the BBC Third Programme:

Dull, verbose and platitudinous as a play, Mr. James Law Forsyth's Bronze Horse was given a production of unparalleled variety and magnificence by M. Michel St. Denis. It set a new standard for radio, and one hopes resident producers will not ignore it, for it suggested space and perspective in a way one had thought impossible on the air. The actors responded to the detailed drilling, and seemed to have overcome that boredom which usually sets in among them if a play is rehearsed for more than a day and a half. Mr. Ralph Truman and Mr. Paul Scofield were outstanding; I hope we may hear more of Mr. Scofield than we have hitherto.

Here is Mr. Bridie's letter to the editor, from the January 31 New Statesman (p. 96):

Bridie obviously held Forsyth in high regard, as a playwright and a fellow Scot. Reed apparently declined to respond. As luck would have it, Bridie's letter appeared on the same day as a letter from Mr. Hans Redlich, to whom Reed did reply.

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

I turned up an interesting exchange in plumbing the depths of The New Statesman and Nation. Alongside Reed's Radio Notes column for February 7th, 1948, in which he assesses Living Writers — a collection of critical talks given on the BBC's Third Programme — was a small, one-paragraph letter to the editor from Reed himself, entitled " Monteverdi's Vespers" (.pdf).

In this letter, Reed is responding (apologizing, really) to a Mr. Redlich, who apparently had a strong reaction to the Radio Notes column of January 24th, two weeks earlier. Reed had reviewed the Third Programme's first three installments of A History in Sound of European Music, and lamented the "vocal inadequacy so often revealed by the Third's resuscitations of ancient music." Reed felt, for example, that the recent broadcast of Claudio Monteverdi's Vespers had left him feeling "embittered and frustrated."

I do not, unfortunately, have a copy of the letter from Mr. Redlich, but I can easily surmise it appears in the January 31st, 1948 issue of The New Statesman. I can also deduce that Mr. Redlich probably knew well of what he spoke, if he is, in fact, the H.F. Redlich, who wrote a great deal on Monteverdi. His opinion would have mattered a great deal to Reed, an unrepentant music snob, which would go far toward explaining his apologetic (if somewhat defensive) tone:

But I hope Mr. Redlich does not really think that I should like to hear a choral work sung throughout in a steady fortissimo. I think I have said nothing to imply that. But I also know that Italian singing can be at times excrutiatingly vulgar.

Incidentally, Reed's reply also mentions his having attended a recent music festival in Perugia, Italy, where he heard the Rome Opera Chorus peform some of Monteverdi's Psalms. The facts of which, I think, are some small justification for this monomaniacal attempt to track down everything written by our particular author. The briefest, 150-word editorial reveals part of Reed's itinerary from his fourth trip to Italy, in 1947.

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

Did you know that the first publication of Reed's "Naming of Parts" was the same day as the UK premiere of Disney's Bambi? The poem appears directly below a panning review in the August 8th, 1942 New Statesman and Nation (link to .pdf document).

There aren't nearly enough laughs in Bambi, and when we stop laughing at a Disney creation it begins to look commonplace [....] The voices are all straight; Bambi's Ma is a bore with fairy-tale intonations; the Great Stag of the Forest is a terrible bore; and heavenly choirs chant interminably, without a tune one remembers.

My photocopy was a particularly poor one, as it was taken from a bound volume of New Statesmans, and I spent several hours washing out the shadows in the page-well to make that .pdf legible. There it is: Bambi, followed by "Naming of Parts."

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|