|

|

Documenting the quest to track down everything written by

(and written about) the poet, translator, critic, and radio

dramatist, Henry Reed.

An obsessive, armchair attempt to assemble a comprehensive

bibliography, not just for the work of a poet, but for his

entire life.

Read " Naming of Parts."

|

Contact:

|

|

|

|

Reeding:

|

|

I Capture the Castle: A girl and her family struggle to make ends meet in an old English castle.

|

|

Dusty Answer: Young, privileged, earnest Judith falls in love with the family next door.

|

|

The Heat of the Day: In wartime London, a woman finds herself caught between two men.

|

|

|

|

Elsewhere:

|

|

All posts for "Auden"

|

|

|

27.7.2024

|

In his essay " Notes on the Comic" (collected in The Dyer's Hand, and Other Essays, 1948) W.H. Auden says, "Among those whom I like or admire, I can find no common denominator, but among those whom I love I can: all of them make me laugh." Telling then, that in the section covering literary parody, he uses Henry Reed's lampoon of T.S. Eliot as the example:

Literary Parody, and Visual Caricature

Literary parody presupposes a) that every authentic writer has a unique perspective on life and b) that his literary style accurately expresses that perspective. The trick of the parodist is to take the unique style of the author, how he expresses his unique vision, and make it express utter banalities; what the parody expresses could be said by anyone. The effect is of a reversal in the relation between the author and his style. Instead of the style being the creation of the man, the man becomes the puppet of the style. It is only possible to caricature an author one admires because, in the case of an author one dislikes, his own work will seem a better parody than one could hope to write oneself.

Example:

As we get older we do not get any younger.

Seasons return, and to-day I am fifty-five,

And this time last year I was fifty-four,

And this time next year I shall be sixty-two.

And I cannot say I should like (to speak for myself)

To see my time over again-if you can call it time:

Fidgeting uneasily under a draughty stair,

Or counting sleepless nights in the crowded tube.

Every face is a present witness to the fact that its owner has a past behind him which might have been otherwise, and a future ahead of him in which some possibilities are more probable than others. To "read" a face means to guess what it might have been and what it still may become. Children, for whom most future possibilities are equally probable, the dead for whom all possibilities have been reduced to zero, and animals who have only one possibility to realize and realize it completely, do not have faces which can be read, but wear inscrutable masks. A caricature of a face admits that its owner has had a past, but denies that he has a future. He has created his features up to a certain point, but now they have taken charge of him so that he can never change; he has become a single possibility completely realized. That is why, when we go to the zoo, the faces of the animals remind one of caricatures of human beings. A caricature doesn't need to be read; it has no future.

We enjoy caricatures of our friends because we do not want to think of their changing, above all, of their dying; we enjoy caricatures of our enemies because we do not want to consider the possibility of their having a change of heart so that we would have to forgive them.[pp. 382-383]

|

1537. Radio Times, "Full Frontal Pioneer," Radio Times People, 20 April 1972, 5.

A brief article before a new production of Reed's translation of Montherlant, mentioning a possible second collection of poems.

|

Look what turned up in the New York Public Library's Berg Collection of W.H. Auden material: Henry Reed's personal copy of Auden's Poems (1933). That's the second edition of Auden's first published poems from 1930, submitted to T.S. Eliot while he was at Faber and Faber.

The library catalog record states the copy 'contains ownership signature, " Henry Reed, 1943" on free endpaper'. That would mean this was a book Reed had with him during the war years, while he was stationed at Bletchley Park ( previously). No word on whether there's any marginalia, however.

The book was a gift given to the NYPL in June, 2007, from Eric H. Robinson. Could that be the Eric Robinson, historian and literary scholar, long claimant to the copyright ( Guardian) of the poems of John Clare (1793-1864)?

|

1536. L.E. Sissman, "Late Empire." Halcyon 1, no. 2 (Spring 1948), 54.

Sissman reviews William Jay Smith, Karl Shapiro, Richard Eberhart, Thomas Merton, Henry Reed, and Stephen Spender.

|

I have had, on occasion, the pleasure of using and perusing the website of Helen Goethals, Professor of English at the University Lumière Lyon 2. Professor Goethals is "interested in poetry and war during the twentieth century," and has several excellent pages devoted to the poets of the Second World War, including a select bibliography and filmography. She even refers to "Naming of Parts" as 'the most famous poem to have come out of the war'.

As a sort of tangent in my hunt for Henry Reed material, I've been reviewing items from the period which ask (or answer) the question, " Where are the war poets?", which came as a lament that no Brooke or Owen or Sassoon was seen to emerge from World War II. So it was with interest that I noted several references in Professor's Goethal's conference papers that the famous question was even raised in Britain's Parliament: in " Talking to India: George Orwell, the BBC, and British Policy Towards the Indian Empire During the Second World War" ( n13), " Philip Larkin and the Poetics of Resistance to the Second World War" ( n15, collected in Philip Larkin and the Poetics of Resistance [Andrew McKeown and Charles Holdefer, eds. Paris: L'Harmattan: 2006]), and " The Muse that Failed: Poetry and Patriotism During the Second World War" (appears in The Oxford Handbook of British and Irish War Poetry [Tim Kendall, ed. London: Oxford, 2007]).

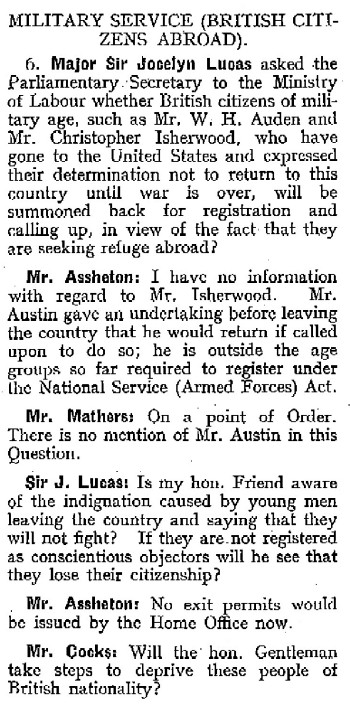

So I was quite surprised when I went to the Parliamentary Debates for June 13, 1940, and discovered that the question raised in the House of Commons was not so much the rhetorical "Where are our war poets?", but the much more literal, "Do you know where Messrs. Auden and Isherwood have got to?"

The question, of course, was what to do about British men of required registration age (between 18 and 41 years old, according to the National Service [Armed Forces] Act of September 3, 1939), who were abroad either by choice or necessity. W.H. Auden had emigrated with Isherwood to New York City in 1939, was 33 years old in 1940, and became a U.S. citizen in 1946.

|

1535. Reed, Henry. "Talks to India," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 3 (15 January 1944): 54-55.

Reed's review of Talking to India, edited by George Orwell (London: Allen & Unwin, 1943).

|

[The following is a letter to the editor, in response to Henry Reed's article, " Poetry in War Time: The Older Poets," which appeared in The Listener on January 18, 1945. Reed's two-part series on the poets working during the period 1939-1944 led to a lively exchange of letters debating the merits of modern poetry, with particular regard to a comparison of the poets of the Second World War and those of the first, Great War. Over the next week, we will reproduce the exchange of letters, here. We begin with the poet and editor, Geoffrey Grigson.]

The Listener, 25 January, 1945. Vol. XXXIII, No. 837. (p. 104) [.pdf]

Poetry in War Time

Writing of 'Poetry in War Time' Mr. Henry Reed says, and says only of Mr. W.H. Auden, that 'Two volumes by Auden have appeared, but they consist mainly of pre-war work'.

In America, in 1944, Mr. Auden's book For the Time Being was published. I daresay few copies have arrived over here; but when Mr. Reed does get hold of one, and does digest Mr. Auden's long commentary on 'The Tempest' which is called 'The Sea and the Mirror', he may overhaul his opinion about who 'has made the greatest contribution to poetry in the last five years'. In my judgment 'The Sea and the Mirror' secures Mr. Auden in the place many of us know him to occupy—as the most inquisitive, moving, serious, the best and most diversely equipped poet now writing in English.

KeynshamGeoffrey Grigson

|

1534. Reed, Henry. "Radio Drama," Men and Books. Time & Tide 25, no. 17 (22 April 1944): 350-358 (354).

Reed's review of Louis MacNeice's Christopher Columbus: A Radio Play (London: Faber, 1944).

|

In my lengthy, involuntary exile, I was remiss in not linking to an excellent reminiscence of Henry Reed's time as a professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, between 1963 and 1967. Ed, over at I Witness (appropriately enough), has two spectacular posts from October last year, recounting his days as an English major and teaching assistant in Seattle, and how Reed came to befriend him and his family.

Part one, " Henry Reed in Seattle," tells the story of how Reed came to be invited to teach at the University of Washington, and features a cameo appearance by the poet Theodore Roethke. The second part, " Typography of the Heart," has tea with Elizabeth Bishop, the occasional opera, and Reed's eventual return to England.

I, myself, have been trying to remember precisely when I first discovered Henry Reed. It was his "Naming of Parts," of course. It was in high school, inside a giant, all-encompassing Norton Anthology we had to purchase for sophomore year. My copy was used, well-used, with the notes of various previous owners in the margins in pen and pencil, passages underlined. The pages were onion-skin thin, almost transparent, and it seemed like every single page could be peeled to reveal another, like Borges' infinite library book.

We didn't even read "Naming of Parts" in class. I would read ahead whenever I was bored with whomever we were covering: Homer, Conrad, Eliot. I remember reading Auden's " Musée des Beaux Arts," distinctly. It was the first truly modern poem I had been introduced to, and I was staggered that I could learn something so profound from (and about) a painting I had never seen, Brueghel's " Landscape with the Fall of Icarus." Just a few pages beyond Auden was Henry Reed. Anytime I wrote poetry for a creative writing class in the years that followed, I was imitating either Auden, or "Naming of Parts."

It would be ten years before I would look Henry Reed up, again. I had a part-time job at the reference desk of my local public library, and I spent my shifts answering the oddest questions from our patrons, like "Where can I find a list of all the times the word 'breast' appears in The Bible?" After a while I knew enough about how the library worked and how the books were organized to try and answer some of my own questions.

There was nothing about Reed online in those days. Most of the library's databases were still on CD-Rom. In Louis Untermeyer's anthology, Modern American and British Poetry, I learned there were two more poems to Reed's Lessons of the War: "Judging Distances," and "Unarmed Combat." There was also a long, long poem called "The Auction Sale." I must have known that Reed had written other poems, but I hadn't been prepared to find two sequels to "Naming of Parts," and certainly nothing as good as "Judging Distances."

And it would be a few more years before I would learn of Reed's death, after I had taken a job at a university library. There, it was easy enough to go to the Reference section—so much more comprehensive than the one at my old public library—and look him up. So I finally found out that Reed had died back in 1986, about the same time I first read "Naming of Parts." But there are biographies in the reference sections of many libraries which haven't been updated since before Reed died, and several printed since which failed to notice his passing, and you can still find him listed in the subject headings of library catalogs online with a heartening Reed, Henry, 1914 - .

|

1533. Friend-Periera, F.J. "Four Poets," Some Recent Books, New Review 23, no. 128 (June 1946), 482-484 [482].

A short review calls A Map of Verona more pretentious than C.C. Abbott's The Sand Castle; influenced by Eliot, Auden, MacNeice, and Day Lewis.

|

A biographer researching the critic John Hayward (1905-65) has turned up "a collection" of unknown (or thought to be lost) poems written by W.H. Auden, published in his teens while he was at Gresham's School in North Norfolk, England. John Smart, a former head at Gresham's turned up the poems ( The Independent) in old volumes of the school's magazine, The Gresham, which Hayward had edited as a student.

In one of the journals, Mr Smart came across a poem entitled 'Evening and Night on Primrose Hill', which, like most of the verse in the magazine, was unsigned.

In her definitive collection of Auden's 'Juvenilia', the author Katherine Bucknell refers to a sonnet the poet wrote about Primrose Hill in north-west London, which had been lost.

The Independent also has a longer follow-up piece on the discovery. (Via dumbfoundry.)

|

1532. Vallette, Jacques. "Grand-Bretagne," Mercure de France, no. 1001 (1 January 1947): 157-158.

A contemporary French language review of Reed's A Map of Verona.

|

Like T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden is a poet who can be claimed by both Britain and the United States (though Auden traveled in the opposite direction). Wystan Hugh Auden was born in York, England in 1907, but emigrated to America in 1939, and became a U.S. citizen in 1946. Auden is at least tangentially connected with Reed, as the Audens lived in Birmingham while he was at university.

The current issue of Bookforum has a delightful profile on what it takes to be the literary executor of someone like Auden (via Light Reading):

Eventually, Auden asked Mendelson to take his place as the editor of the collection [of essays] and sealed the deal with a $150 check for photocopying expenses. Mendelson was so happy that, as he tells it, he jumped up and down. As their collaboration progressed, the poet was also pleased. According to Mendelson, who took the liberty of vetoing an essay that he thought wasn't very good, Auden was grateful for the critical judgment—plus, "he was delighted to have somebody actually pay attention to proofreading." When the project neared conclusion, Auden asked Mendelson in the postscript to one of his letters to be his literary executor. Mendelson agreed. In the end, the photocopying only cost $110, so he sent the poet $40 back.

To honor the centenary year of Auden's birth, a number of events have been scheduled to celebrate the poet's life and work, including readings and tributes, a BBC4 television special, and martinis served at his birthplace, on his birthday, February 21.

|

1531. Henderson, Philip. "English Poetry Since 1946." British Book News 117 (May 1950), 295.

Reed's A Map of Verona is mentioned in a survey of the previous five years of English poetry.

|

|

1530. Radio Times. Billing for "The Book of My Childhood." 19 January 1951, 32.

Scheduled on BBC Midland from 8:15-8:30, an autobiographical(?) programme from Henry Reed.

|

|

|

|

1st lesson:

Reed, Henry

(1914-1986). Born: Birmingham, England, 22 February 1914; died: London, 8

December 1986.

Education: MA, University of Birmingham, 1936. Served: RAOC, 1941-42; Foreign Office, Bletchley Park, 1942-1945.

Freelance writer: BBC Features Department, 1945-1980.

Author of:

A Map of Verona: Poems (1946)

The Novel Since 1939 (1946)

Moby Dick: A Play for Radio from Herman Melville's Novel (1947)

Lessons of the War (1970)

Hilda Tablet and Others: Four Pieces for Radio (1971)

The Streets of Pompeii and Other Plays for Radio (1971)

Collected Poems (1991, 2007)

The Auction Sale (2006)

|

Search:

|

|

|

Recent tags:

|

Posts of note:

|

Archives:

|

Marginalia:

|

|