Here's a clip of Professor Willard Spiegelman of Southern Methodist University, talking on Henry Reed's "Naming of Parts" part of The Great Courses lectures, How to Read and Understand Poetry (1999):

Spiegelman uses "Naming of Parts" as an example of "irony as dialectic", and brilliantly even spends a minute to explain Reed's switch of "duellis" (battles) for "puellis" (girls) in the poem's epigraph from Horace.

|

How to Read and Understand Poetry

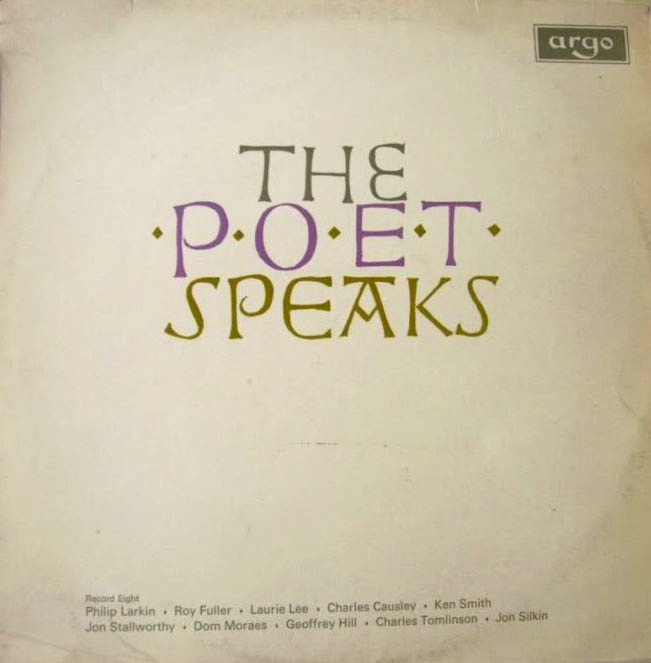

Henry Reed Reads "The River"In 1970, Henry Reed was recorded reading eight of his poems, as part of a series co-sponsored by the British Council and the Woodberry Poetry Room in the Lamont Library of Harvard University. The series was The Poet Speaks, created by Peter Orr, then the head of the Recorded Sound Department at the British Council.

Not only were contemporary British and American poets invited to record their work, but they were interviewed by Orr, Hilary Morrish, John Press, and Ian Scott-Kilvert: talking about poetry, the craft of writing, and being a poet (notably among the interviewees, Sylvia Plath). Many of these recordings were released on LP records by Argo Records, starting in 1965. Some of the recordings for The Poet Speaks, however, were never commercially released, including those of Henry Reed. But they still exist on reel-to-reel tapes, thanks to the preservation efforts of the Houghton Library at Harvard University (TAPE ARCHIVE PR6035.E32 A6 1970x). Here's just a sample in honor of National Poetry Day in the UK, Henry Reed's "The River": "The River" was published in The Listener on March 26, 1970, along with another of Reed's poems, "Three Words." This recording is reproduced with the generous permission of the British Council, the Woodberry Poetry Room at Harvard University, and the Royal Literary Fund. And there's more. Much more, coming soon!

Naming of Parts, LiterallyBen Mellor is a Manchester-based, award-winning slam poet. His first full-length spoken word show, Anthropoetry (with music by Dan Steele), is a linguistic road trip through the human body, and includes this spin on Henry Reed's classic "Naming of Parts":

Other Ranks: Naming of PartsThis audio clip is part of "Other Ranks," an installation by sound artist Amie Slavin at the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds, England (extended until July!). It features the actor Jim Broadbent reading Henry Reed's poem "Naming of Parts" over the sounds of soldiers drilling:

You can listen to other works by Ms. Slavin — including an introduction to "Other Ranks" — on her SoundCloud stream.

Secret ScienceI can't wait to get home and listen to the latest episode of BBC Radio 4's The Infinite Monkey Cage, with Brian Cox and Robin Ince. This week features comedian Dave Gorman, Simon Singh, and Dr. Sue Black, talking about the science of WWII cryptography and Bletchley Park.

The episode runs about 30 minutes.

A Little Pat of ButterHenry had a cameo appearance on BBC Radio 3's Composer of the Week yesterday, in which Donald Macleod presented a history of musical fictions and hoaxes, "Unbelievable Spoofs." Well, not a cameo by the Old Man himself, but one of the plays from his Hilda Tablet series:

With the help of silent film accompanist Neil Brand we meet such dubious figures as Bolognese theatre composer Lasagne Verdi, famously submitted (and nearly printed) in the music world's most trusted encyclopedia, served for good measure with an accompaniment of Pietro Gnocchi. There's a chance to hear the music of Pietro Raimondi, the man who composed three oratorios to be performed simultaneously, centuries before Charles Ives conceived of such an adventure. Avant-garde composers reemerge from the BBC archive too, including Hilda Tablet whose 'reinforced concrete music' found its way into the repertory of Covent Garden in the 1950s. Plus a bizarre encounter with the man said to be a reincarnation of Merlin and Francis Bacon, variously described as a courtier, adventurer, charlatan, inventor, alchemist, pianist, violinist and amateur composer. But did he really exist? You'll have to make up your own mind. Here, Mr. Macleod introduces a clip from Reed's satirical, all-female opera, Emily Butter (1954), ostensibly written by the twelve-tone composeress Hilda Tablet, supposedly performed at the Royal Opera House. This bit is "I Have a Little Mark On My Left Upper Arm": Mr. Macleod says the performers are "unnameable," but Emily was, of course, famously voiced by Marjorie Westbury. Here is the 1960 Times "interview" with Dame Hilda, which is mentioned. The music for Emily Butter was written by the incomparable Donald Swann, and orchestrated by Max Saunders. Read The Times review of the original BBC Third Programme broadcast, from November 15, 1954. Follow this link to listen to "Unbelievable Spoofs" in its entirety, until March 25. Thanks to the folks at the Friends of Radio 3 forums for leading me to this broadcast!

Jammed at the SommeOur constant friend, Bruce, directs us to a lecture by Professor Jon Stallworthy, speaking at the Teaching World War I Literature Conference, held at Oxford University Computing Services, in November of 2007. The conference was convened (according to Stallworthy) in order to discuss the teaching of First World War literature in secondary and tertiary education, with special reference to three topics: 1) The relevance, today, of the poetry of the Great War, 2) whether the canon of that poetry should be extended, and 3) the wider topic of war poetry, and how the poems of the Great War should fit into that category.

Stallworthy argues that society today is suffering from a sort of "trench-tunnel vision," and that our collective newsreel seems to be "jammed at the Somme, in 1916." He makes the case that the current curriculum could be benefited if it "replaced some of the weaker poets of the First World War with some of the stronger poets of the Second," and he goes on to outline such a syllabus, to include: the call to arms for poets during the Spanish Civil War; the American poets; poems by veterans; and, specifically, the work of John Balaban, a conscientious objector who was in Vietnam during the Tet Offensive. The talk is about 30 minutes long: Professor Jon Stallworthy, Teaching World War One Literature Amusingly, at several points during his presentation, Stallworthy is compelled to admit that he, himself, is at least partly to blame for the continuing over-emphasis on and popularity of First World War poetry. There also appears (at about 7:15) an amazing mention of a failed proposal to install a plaque at Poet's Corner for the poets of World War II, including Henry Reed. Stallworthy says: How often have we all had to ask the question, 'Why, when there was so much marvelous poetry from the First World War, was there none from the Second?' The double misperception can only be the fault of an educational system that over-values the one, and is ignorant of the second. If you doubt the accuracy of that statement, consider these facts: First, that in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey, a stone commemorating the poets of the Great War carries the names of Laurence Binyon, Wilfred Gibson, Robert Nichols, and Herbert Read, among others. Second, that the Dean of Westminster and his advisors have rejected a proposal that a similar stone, commemorating voices from the Second World War, should be erected to carry the names of four much better poets (of whom I'll have more to say, later): Keith Douglas, Sidney Keyes, Alun Lewis, and Henry Reed. Curiously, I can't find any other references to the proposed memorial for World War II poets. That would be a big deal! Do you know anything about it? Professor Stallworthy's talk is archived on the "Podcasts" page of The First World War Poetry Digital Archive. (And he is in good company, with Tim Kendall presenting a paper on Ivor Gurney, just below!)

Best of Second World War PoetryOver on Yahoo! Music, I was shocked to find available, free for listening, all 118 poems from the album Best of Second World War Poetry (CSA Word Recording, 2007). Read by Rosalind Ayres, Phil Collins, Barry Humphries, Martin Jarvis, and Richard Todd, the anthology includes poems by Roy Campbell, Keith Douglas, Gavin Ewart, Sidney Keyes, and Terrence Tiller.

Reed is, of course, represented by the ever-present "Naming of Parts," read by the actor Martin Jarvis. Individual tracks, or the entire album, are available for purchase from Rhapsody, and the Commemorative Special Edition CD set (shown above) is on the CSA Word website.

Book of the Year, 1991This brief endorsement from the Financial Times was written by Anthony Curtis, the paper's former literary editor. It's from December 7, 1991 (p. XVI):

Books: My Book of the Year— Collected Poems of Henry Reed Today our writers and critics nominate the books they have enjoyed reading most over the last twelve months. No rules were imposed but, as you will see, all have been encouraged to be adventurous and broaden their interests away from their usual subjectsOne of the saddest experiences I have had was to observe the decline of the poet Henry Reed in the latter part of his life. He became a recluse in his London flat, reluctant to accept any invitation, producing nothing. Apart from the frequently anthologised 'Naming of Parts' and the occasional reference to one of his radio classics such as Hilda Tablet, the so gifted Henry was, it seemed, by the world forgot. I was therefore delighted when Collected Poems of Henry Reed, edited and introduced by Jon Stallworthy (Oxford), appeared this year. Here at last are the Arthurian and classical poems, the Leopardi translations, and poems from the radio plays, all of them where they belong—with The Lessons of War. Now we need the same excellent job done for Reed's prose. It definitely sounds as though Mr. Curtis was a friend of Reed's. Oddly enough, finding his praise in Factiva, I discovered the database offers a text-to-speech service (.mp3), from ReadSpeaker (Reed speaker?). There's a brief advertisement before the article begins.

Quote... UnquoteLast Monday on Radio 4, the BBC quiz program Quote... Unquote featured the theme of "Fakes," including a round of quotes from parodies. One question was on the opening lines from Reed's (of course) "Chard Whitlow": what is it parodying? Here's the relevant clip, featuring host Nigel Rees, reader Peter Jefferson, and guest Adèle Geras:

Chard Whitlow on Quote... Unquote You can listen to the entire show—with additional guests Conn Iggulden, Christopher Luscombe, and Simon Pearsall—on the Quote... Unquote website, until next Monday, when the new program is scheduled to air. (With thanks to Underbelly.)

The Poet SpeaksIn the 1960s, the British Council teamed up with the Harvard Library Poetry Room to record contemporary British and American poets reading from their own work, and in interviews discussing poetry and the process of writing. English poets who participated in the project included John Betjeman, C. Day-Lewis, William Empson, Hugh MacDiarmid, Louis MacNeice, Kathleen Raine, Stephen Spender, John Heath-Stubbs, W.R. Rodgers, and Vernon Watkins, to name just a few. Interviews were conducted by Ian Scott-Kilvert, Hilary Morrish, Peter Orr (head of the British Council's Recorded Sound department), and John Press. A few details are mentioned in "Poetry, for Crying Out Loud," a 1999 Independent article.

The final product of these recordings was a set of ten LP records released by the Argo Recording Company, along with an accompanying book of transcripts called called The Poet Speaks: Interviews with Contemporary Poets (London: Routledge, 1966).  The project didn't end when the record collection was produced, however, because we can find recordings of a 1970 interview with Henry Reed, both at the British Library Sound Archive, and at Harvard's Poetry Room: "Interview with Henry Reed sound recording, by Peter Orr, British Council Recorded Sound Dept., June 11, 1970." Alas, the Reed interview was too late to get included in the Poet Speaks project. The Woodberry Poetry Room at Harvard has one of the largest collections of recorded poetry in the world. Sadly, they provide only a few links to select recordings on their homepage (and several of those do not seem to be working, currently).

St. Petersburg is More than Twice as Little as MoscowI think Zhopa Novy God (MySpace) is my new favorite Russian festive brass band. Their track, "St. Petersburg is More than Twice as Little as Moscow" (YouTube), defines everything I love about Russian festive brass.

Duelling AccentsHere's a linguistic experiment conceived by our friend and counterpart, the Webrarian. It's Reed's "Naming of Parts" being read as a duet of sorts. The parts in the voice of the Sergeant-Instructor have been re-recorded in an Essex accent, while the voice of the Private is the original recording, read by Reed himself:

Smithsonian SoundsOne of the things I really wanted to know, when I listened to Oscar Williams' Album of Modern Poetry (1959), was whether or not Reed's "Naming of Parts" was different than the other recordings I had already heard on other albums.

For instance, the Smithsonian Institution's Global Sound offers 99¢ downloads of audio samples and music from almost every country in the entire world; offering everything from tribal music to fiddle tunes, including spoken word records. It's an amazing cultural archive. One album in particular, Folkways' Anthology of 20th Century English Poetry (1961), has poetry by Reed and his contemporaries John Betjeman, Roy Fuller, Laurie Lee, C. Day Lewis, W.R. Rodgers, and Vernon Watkins. The liner notes for Part II (.pdf) state that these recordings were 'directed by V.C. Clinton-Baddeley, and made by Edgar A. Vetter at 22b, Ebury Street, London, S.W.1, Summer 1958' (Google Maps). I've listened to "Naming of Parts" on both the Anthology of 20th Century English Poetry and An Album of Modern Poetry, and I can safely report that they are definitely two different recordings. Not just different: the Smithsonian's copy of "Naming of Parts" is vastly superior in terms of tone, quality, and clarity. It does sound a bit like he's reading in an empty Tube station, but (in my opinion) Reed gives a more powerful performance on the Folkways' record. The track is only 99¢, and you can get the whole album for just $9.99. But you don't have to take my word for it. You can join Smithsonian Global Sound and listen for yourself, or just explore what they have to offer. A quick search for "poetry" brings up 59 albums, and 801 tracks!

An Album of Modern PoetryLast September, I mentioned discovering a letter to Henry Reed in the collection of Oscar Williams' correspondence at the Lilly Library in Indiana. The letter was from Henry J. Dubester, and was among a group of letters addressed to British and American poets, including Auden, William Empson, Frost, Roy Fuller, Archibald MacLeish, Roethke, and Stephen Spender (amidst many others). I wondered, at the time, what Mr. Dubester was doing, writing to so many prominent poets?

Not long after, I received an e-mail from none other than Henry Dubester, himself, which answered my question. Mr. Dubester informed me: I was promoted and served as Assistant and then Chief of the General Reference and Bibliography Divisions of the Library of Congress. The Poetry Office was one of the sections of the Division. The Library also had a recording laboratory where recordings were made and preserved of many individuals, including poets. I had the opportunity of compiling a set of records with a selection from those recordings. Oscar Williams was my consultant who advised me on the selection. Following his advice, I contacted the poets and solicited their permission to include the text of their recorded poems with the (3) record album. Mr. Dubester is referring to the Library of Congress Recording Laboratory's An Album of Modern Poetry: An Anthology Read by the Poets (1959), a set of recordings of the best 20th-century poets reading from their own work, edited by Williams. My library actually owns these records, although I had to request them from the storage facility where they cache the more outdated or under-utilized materials. The library also possesses a spectacular media lab of its own, replete with soundproofed recording booths stuffed with just the right gear for analog-to-digital conversion. Which is? An ancient turntable plugged into a Mac. So I snuck away for an hour today, and lifted the tracks of "Naming of Parts" and "Judging Distances" from Williams' Album of Modern Poetry. The boxed set is three 12", 33 1/3 microgroove LPs, pressed into a vinyl the color of which there is no word for in English ("vermillion" does not adequately convey the records' ethereal translucence). As Mr. Dubester promised, the set includes a wonderful, 41-page printed anthology of the poems being presented by their authors, as well as an introduction from Oscar Williams on the box. And, I did enjoy a wonderfully surreal moment, when I heard Conrad Aiken's voice booming from the lab's speakers, repeatedly referring to Rambo, Rambo, Rambo, before I realized he was talking about Rimbaud. But, enough. 'This is Henry Reed, reading selections from his poems': "Naming of Parts" (.mp3) "Judging Distances" (.mp3)

Norton AudioThe website of one of my favorite books of poetry to browse on rainy days (and least favorite to try and lug around), The Norton Anthology of English Literature, has a few dozen audio samples of poets reading from from their own work, and others'.

The 20th century is represented by poets like W.H. Auden ("Musee des Beaux Arts"), Eavan Boland ("That the Science of Cartography Is Limited"), Ted Hughes ("Pike"), Philip Larkin ("Aubade"), Edith Sitwell ("Still Falls the Rain"), and Dylan Thomas ("Poem in October"). There are also examples of poems from other periods to have a listen to, including the Middle Ages (Seamus Heaney reading from Beowulf), the 16th and early 17th centuries, the Restoration and 18th century Romantics, and the Victorians. While I'm at it, check out this page of poems at the BBC: Poetry Outloud.

Everybody Loves RalphThat's "Rafe," not "Ralf." Rrrrafe. Roll your "r": R-r-r-r-r-rafe.

On a fansite for Ralph Fiennes, there's a "Poetry Corner" page, which collects recordings of the actor reading all sorts of verse, from Shakespeare to Kipling to Pablo Neruda. This, in itself, is not surprising. But I was left completely nonplussed to discover Ralph Fiennes reading "Naming of Parts" (.mp3). He does the two voices, and everything! Just when you thought the Internet wasn't, y'know: good for stuff. The poem appears under a section for BBC Radio 4's program, "Poetry Please," so I have to assume this to be the recording's origin. The section also includes Fiennes's interpretations of Keith Douglas's "Vergissmeinnicht," and John Gillespie Magee's "High Flight."

A One, and a Two, and a One-Two-ThreeWho gives a fuck about an "Oxford Comma"? (.mp3), by Vampire Weekend. (Via Steamboats Are Ruining Everything.)

Monteverdi (Reprise)I was neglectful and lazy in my last post, for not providing a more authoritative and interactive link to Monteverdi's Vespers (index of .mp3s). Shame on me!

Audio Follow-UpAs an early-morning follow-up to yesterday evening's post, I should point out the British Library's Archival Sound Recordings Project, which, as a pilot program, has set a goal of digitizing 4,000 hours of audio recordings, and making them freely available to educational communities in the U.K.

The project is funded by the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC), which interviewed both the Head of the Sound Archive, and the Archival Recordings Project Manager back in 2005. Sample audio from the Sound Recordings Project includes the poet Simon Armitage reading "Entrance," Tolstoy's Waltz in F, and the call of the Tawny Owl (all links to Real Audio files). The full list of audio samples is on the project's "Listen" page.

In Their Own VoicesAges ago, when I was working at a public library circulation desk, someone checked out a set of audio tapes of James Joyce's Ulysses. Having worked at the library for some time, I hardly took notice of what people were checking out: after a while, the books become just product that barely registers, like so many blocks of wood.

These cassette recordings caught my attention, however, because I happened to notice the narrator: it was none other than Joyce, himself. Never had it occurred to me that such a thing could exist, despite the fact that the phonograph had been around since 1877, and Joyce lived until 1941. A recording of the author reading Ulysses seemed impossibly anachronistic. Which is why this BBC article caught my eye: Andrew Motion, the UK Poet Laureate, has founded the Poetry Archive, an effort to present recordings of poets reading their own work, in order to "help make poetry accessible, relevant and enjoyable to a wide audience." Available among the recordings are such historic poets as Kipling, Sassoon (reading "The Dug-Out"!), Tennyson ("The Charge of the Light Brigade," no less), and Yeats ("The Lake Isle of Innisfree"). The mere existence of all these tracks caused me no end of cosmic dissonance. Although Reed himself is absent from the archive, many of his contemporaries are represented, including Louis MacNeice and Vernon Scannell. The recordings are presented as embedded RealAudio, but according to one of the developers, there's still hope of better access to the files (plus, a picture from the launch party).

A Little VincenzoOn March 29th, 1955, the BBC's Third Programme broadcast for the first time Henry Reed's radio play, Vincenzo. The play, advertised as a "tragi-comedy," was something of a prequel to Reed's 1952 The Great Desire I Had. Both plays recount episodes in the life of Duke Vincenzo I of Gonzaga (Wikipedia article), patron of the arts and ruler of the Italian Duchy of Mantua from 1587 to 1612.

The London Times called the play "splendidly acted," and "the happiest association of playwright and players" (March 31, 1955, p. 10). It was produced by Douglas Cleverdon, with music by Denis Stevens. It stars Hugh Burden (Internet Movie Database) as Vincenzo, Rachel Gurney as Ippolita Torelli (later of Upstairs, Downstairs), Gwen Cherrell as Margherita Farnese, Barbara Lott as Eleanora dé Medici, and Barbara Couper as Agnese del Ceretto. The music was arranged by Denis Stevens (Guardian obituary) from the work of Mantuan composers of the period, including Claudio Monteverdi, the Italian master who was Stevens' particular passion. Monteverdi's patron was none other than Duke Vincenzo. The play traces Vincenzo's life from his eighteenth year until his death in 1612, framed in "choric narration" (Savage, "The Radio Plays of Henry Reed") spoken by his wives and mistresses. In Poets of Great Britain and Ireland 1945-1960, vol. 27 of The Dictionary of Literary Biography (Detroit: Gale Research, 1984), Douglas Cleverdon says: ‘Vincenzo is a remarkable work. Its understanding of human character, its erotic power, and its deep compassion are conjoined with delicate satire and delicious comedy. The language ranges from enchanting descriptions of the rose gardens of Colorno to witty bantering between lovers or the biting invective of family quarrels or the anguish of love nobly controlled. There are scenes that haunt the memory: Francesco de Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and his mistress Bianca Cappello lying together on their deathbed, unable to reach each other for one last kiss, but never renouncing their love though it condemned them to an eternity of damnation; or Vincenzo and his five-year-old Silvio sharing, entranced, the sufferings depicted in the seventeenth-century composer Monteverdi's "Lament of Ariadne" as she mourns the departure of Theseus. After Vincenzo explains that "in the end you will see that she is rescued and made happy by Bacchus, the god of wine," Silvio asks, "Are unhappy ladies always rescued from their sorrow by the god of wine?," and Vincenzo responds, "Very frequently, yes."’ (p. 280)A recording of the two-hour broadcast of Vincenzo is available from Schola Antiqua, a version produced by Stevens' Accademia Monteverdiana. Here, ladies and gentlemen, is a 20-minute audio clip, to get you started, opening with those 'enchanting descriptions of the rose gardens of Colorno': Vincenzo, by Henry Reed (8MB .mp3 file)

Dylan Thomas Reads Aloud'Someone's boring me. I think it's me.' Dylan Thomas recorded dozens of hours worth of spoken word performances for Caedmon Records, starting with the album A Child's Christmas in Wales and Five Poems, in 1952. To celebrate a half-century of spoken word publishing, Caedmon (now part of HarperAudio) has published an eleven-CD set of the complete recordings, Dylan Thomas Unabridged.

The collection includes his most famous poems, "Fern Hill" and "Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night"; prose works such as Adventures in the Skin Trade and Quite Early One Morning; as well as his final play, Under Milk Wood. For a limited time [actually, since 2002!], Salon.com is offering free downloads of the complete Dylan Thomas Caedmon Collection, with whole discs compressed as .zip files, or as individual .mp3s. (If you're not a registered member, you'll have to sit through an advertisement, but it's more than worth it. Get a day pass.) Disc 5 of the set contains Thomas reading two poems by Henry Reed: "Naming of Parts," and "Chard Whitlow" (right-click and select "Save as" to download .mp3s). Although I am dismayed they could spell neither Reed's name nor 'Whitlow' correctly. Thomas' interpretation of Reed's poems is superb, if a little heavy on the satire. He even does a passable impersonation of T.S. Eliot. In a 1955 letter to her brother, Edith Sitwell mentions hearing a recording of Thomas reading "Chard Whitlow": ‘...that naughty Dylan made a record (whilst reciting at Harvard) of Henry Reed's really brilliant parody of "Burnt Norton" in Tom's exact voice! (Don't tell anyone, as it will 'get round'.) Each line ended with an absolute howl of laughter from the audience, but Dylan, with noble dignity, paid no attention to these interruptions... The record has not been published.’ (Selected Letters of Edith Sitwell, edited by Richard Greene, p. 359.)I can't be sure without checking a good Thomas biography, but I think the link above may be the exact recording Sitwell is referring to. By the way: this opening speech, "A Visit to America—An Irreverent Preamble", is flipping hysterical.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||